Defining Conflicts

A Core Topic of Modern Japan

The period of modern Japan covered in this online portal is fraught with conflict and military campaigns. Here we highlight some of the most important moments as a background to encourage a broader understanding of the related propaganda from this era. Contributors from the publication Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan (2021) include Toshihiko Kishi, Barak Kushner, Michael Auslin and Olivia Morello, and Kaoru (Kay) Ueda; as well as contributing Hoover Student Fellow Chaeri Park.

| The Imo Incident

The Imo Incident was an uprising that began on July 23, 1882, in Seoul by Korean soldiers who were dissatisfied with their treatment by the government. In 1881, new military reforms were initiated by the pro-Japanese faction of the government and a modern-style military division, the Byeolgigun or "Special Skills Force," was established and trained by a Japanese instructor, Horimoto Reizō. The regular Korean army units were discriminated against in favor of the newly established force, including their wages not being paid on time.

In June 1882, when the 13-month delinquent wages were compensated by providing only one month's worth of rice mixed with sand, the regular Korean soldiers revolted in anger. The Japanese Byeolgigun instructor was assassinated, and soldiers focused their anger on attacking pro-Japanese groups and the Japanese legation. The broader population later joined the uprising as many Korean commoners were also disgruntled with the government.

There was disagreement among Korean political elites on the methods, concepts, and speed of the enlightenment reforms, leading to increasing disorder. They were divided into radical and moderate reformist factions led by the pro-Japanese and pro-Chinese elites, respectively. n added dimension to the social turmoil was a power struggle between the faction led by Daewon'gun, King Kojong's father, and a faction led by the family of Queen Myeogseong (known as Queen Min). Daewon'gun wanted all foreign powers rejected within Korea. He tried to use the soldiers' uprising against his political rivals, but the pro-Chinese faction led by the Queen won and gained more influence in Korea.

When the Imo Incident broke out, the Japanese Minister to Korea, Hanabusa Yoshimoto, gave orders to burn the Japanese legation. It was perhaps to escape under cover of flames and smoke and likely to protect state secrets by ensuring the destruction of confidential documents. The members of the legation successfully escaped to Japan. After the incident was settled, Japan asked the Korean government to compensate for the burning of the legation. Damages and concessions were agreed in the 1882 Chemulpo Treaty, which allowed Japan to send military power to protect the Japanese legation and the Japanese nationals in Korea. Three years later, the Tianjin Convention would attempt to balance Japanese and Chinese influence over Korea by making it a co-protectorate.

Background Image (detail of): Utagawa Kunimatsu (1855–1944). The Defense Against Korean Mobs, August 20, 1882. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113)

| The Nagasaki Incident

Arguably, Japanese national mobilization toward the expansion of empire began in the early Meiji era, but it took full root in the 1890s in the country’s attempt to dominate East Asia. It was not always, of course, a smooth process, nor was Japan’s victory preordained. In actuality, the linchpin in the early modern era can be traced back to August 1886, when several naval vessels of the powerful Qing dynasty northern fleet pulled into the port of Nagasaki in southern Japan. This was the start of imperial conflict between a Qing dynasty flexing its muscles and the upstart Japanese feeling the impact.

Japan was only twenty years into its Meiji project to renovate the nation and judgment was still out whether it would be able to succeed and modernize. Along with numerous other ships, the Qing fleet included several massive ironclad vessels, the prize of the squadron being the Dingyuan (定遠) and the Zhenyuan (鎮遠). The Dingyuan was considered one of China’s premier warships and dominated anything the Japanese maintained in their arsenal. In the late summer of 1886, within a few days after docking during its tour of maritime East Asia, dozens of Qing sailors from the ships had a rollicking time in the Maruyama red-light section of Nagasaki. Riots with Japanese police and the public escalated to the point that pleas from local officials to the Qing consulate in town were dispatched. In the end, the disturbances left seventy-four injured, with two Japanese and five Chinese sailors dead.

The Nagasaki Incident, as it came to be known, created a notoriously bad image of Chinese naval behavior on the archipelago. In part, this interaction unleashed a competition for supremacy in the region that would continue to feed behavior on both sides, pushing the Japanese to develop their subsequent imperial superiority.

Background Image: Tamakura K. (nd). Nagasaki, circa 1891. Hand-colored albumen print. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art (82.67.22)

| The First Sino-Japanese War

1894–1895

The Sino-Japanese War saw Japan for the first time deploy its recently modernized military in an international conflict. Tension erupted between the two Asiatic nations over the status of the Korean peninsula. China regarded Korea as its tributary and maintained involvement in Korean affairs. Japan, although professing to promote Korean independence, viewed the peninsula as an opportunity for further expansion into Asia. Underlying this struggle for control over Korea was Japan’s preoccupation with the colonialization of Asia by Western powers. Since the First Opium War (1839–42), Western encroachment into Asia became a clear threat. To Japan, adopting Western technology and customs and modernizing the nation appeared to be the only ticket for survival. The Japanese viewed the Sino-Japanese War as a test to determine whether it or China would prove to be the leader of the East, ready to take on the mantle of defending Asia from the West.

The Donghak Peasant Revolution, a rebellion on the Korean peninsula in January 1894, was a direct trigger for stationing Japanese and Qing Chinese troops in Korea, triggering the first conflict that impacted the entirety of East Asia. The combat zone between the two nations expanded from the Korean peninsula to the Yellow Sea, the Liaodong Peninsula, the Shandong Peninsula, and finally to the Penghu and Taiwan proper territories that were ceded to Japan after the war.

In the ensuing years after the Nagasaki Incident, Japan had poured precious national funds into augmenting its naval strength. When the two clashed in the Yellow and Bohai Seas, world opinion assessed that the much larger and more powerful Qing forces would quickly triumph over the more poorly equipped and outnumbered Imperial Japanese sailors. However, corruption and inadequate military strategic command within the Chinese ranks opened up opportunities that the Japanese exploited. The Qing were routed. It was not a row that immediately gained public attention, and most Chinese expected the Qing dynasty would ultimately be victorious. Chinese newspapers touted such opinions to the public. The Chinese media referred to the Japanese as “dwarf pirates” (倭寇), a belittling but long-standing traditional epithet, and rarely reported the actual results of battles. This lopsided view of information created a situation in which many Chinese were surprised that the war was actually lost when news of surrender negotiations suddenly appeared in the spring of 1895.

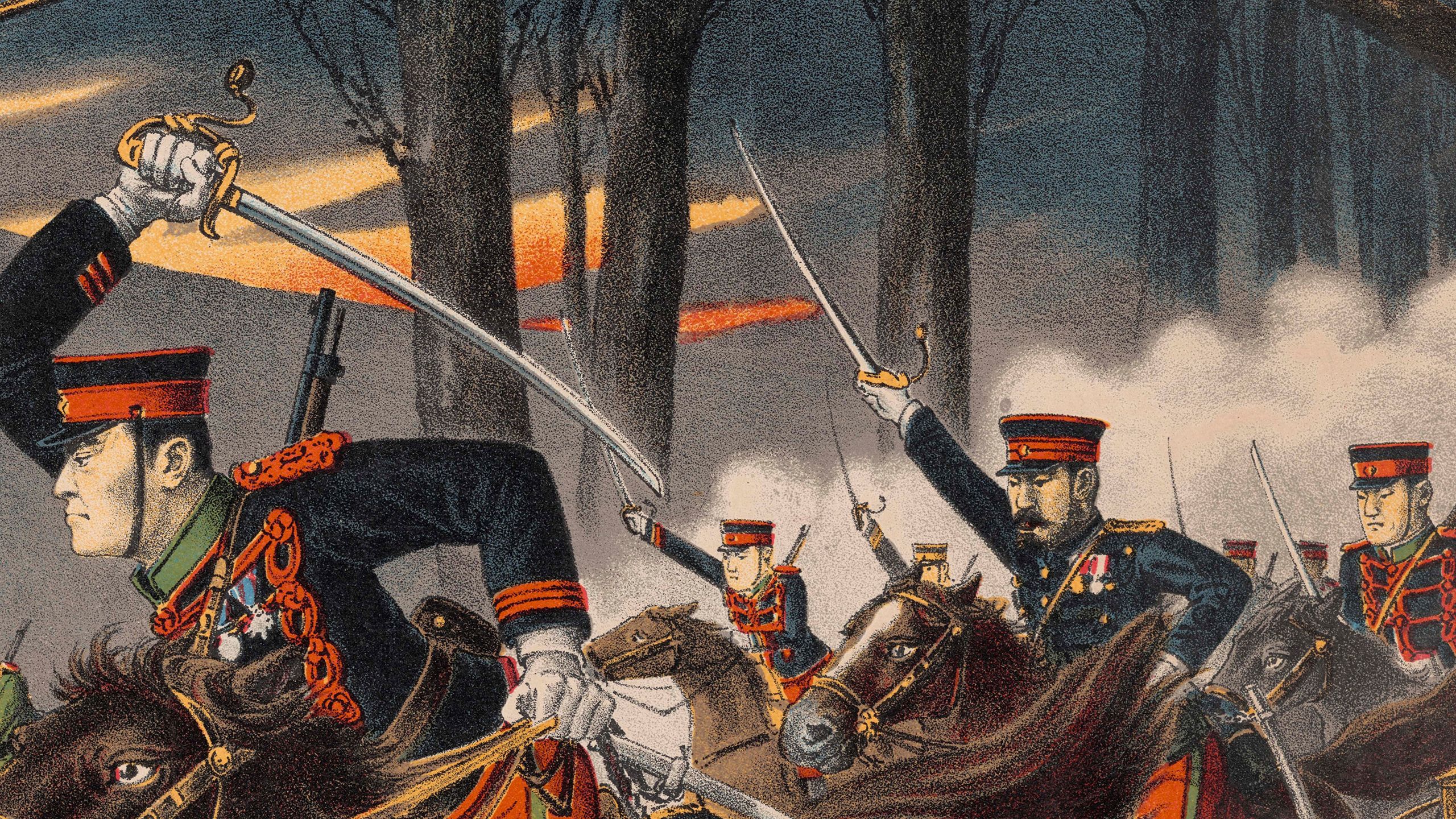

Background Image: Utagawa Kuniteru III (1848–1920) / signed Toyosu. General Nozu’s Great Victory after the Fierce Battle at Pyongyang, September 1894. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.007)

Timeline of Major Events

Map with Major Battle Sites

| The Russo-Japanese War

1904–1905

The outcomes of the Sino-Japanese War in 1895 helped lay the foundation for the Russo-Japanese War almost a decade later. In addition, Russia’s expansion of its territory in the East during the 1860s had led many Japanese to worry that Russia would attempt to dominate all of Asia. As Japan modernized and strengthened its military during the Meiji period, it also began to desire the expansion of its own empire. This imperialist goal was one of the driving forces behind Japan’s participation in the Sino-Japanese War.

Within eight months, the Japanese had defeated the Chinese and had drawn up a treaty that granted Korea independence and Japan the territories of Formosa, the Pescadores Islands, and the Liaodong Peninsula. This treaty alarmed Russia, and before it could be signed, Russia garnered support from France and Germany for the Triple Intervention, which forced Japan to give up its claim on the Liaodong Peninsula. Tensions continued to grow as Russia and Japan maneuvered their control over Manchuria and Korea. When multiple negotiations between the two powers failed to resolve their territorial disputes, the Japanese finally attacked Port Arthur—which China was leasing to Russia—in February 1904, ushering in the start of the war.

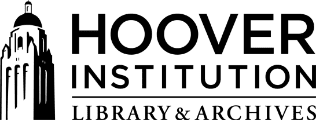

The Russian Fleet at Port Arthur, circa 1904. Photograph affixed to scrapbook page. Lloyd Reise Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

The Russian Fleet at Port Arthur, circa 1904. Photograph affixed to scrapbook page. Lloyd Reise Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

As the first modern war between Asian and European nations, the conflict over hegemony in Manchuria and the Korean peninsula was fought without China. Concerned about a repeat of the First Sino-Japanese War, Qing China declared itself neutral four days after the conflict erupted, when the new conflict expanded south of the Great Wall to include Shandong Province.

Negotiations for a peaceful resolution to Russia’s strong military presence in Manchuria, a remnant of their assistance against the Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901, and its influence over Korea proved untenable to the Japanese by 1904. The bravado which permeated Russia’s position was not lost on their adversaries and the commencement of a naval assault on the fleet harboured at the Russian fortified naval base of Port Arthur left both the Tsar—and most of the world—in shock. The attack came three hours before the declaration of war by Japan reached the Russian government on February 8th, yet this strong initial blow did not provide the Japanese Imperial Navy the safe water haven in the Yellow Sea they desired. Instead they initiated a blockade and a multi-month siege.

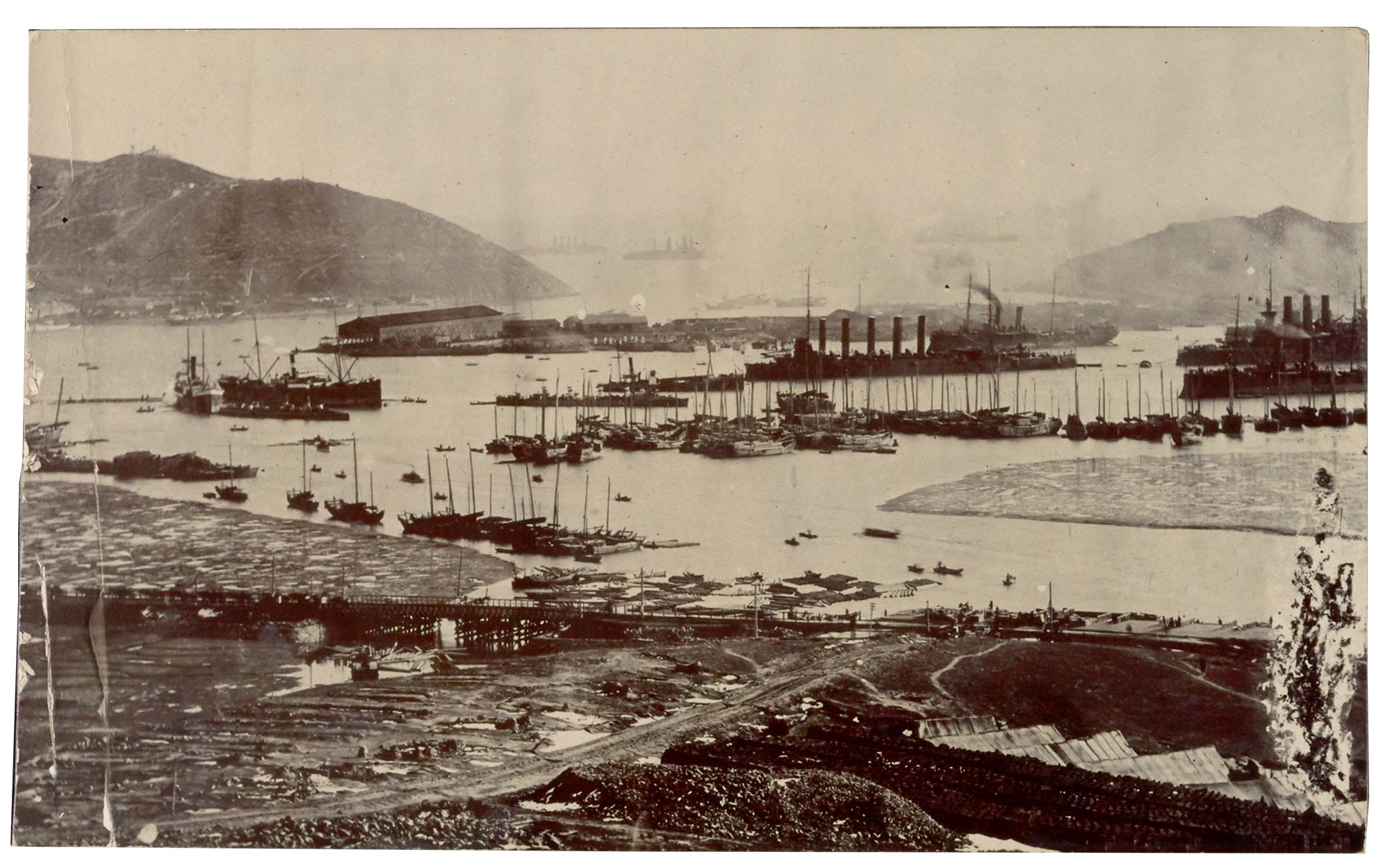

Occupied with their own defenses, Russia was blindsided as the Japanese landed at Incheon and made a quick conquest of the Korean peninsula. Moving their forces to meet the Russians at the Yalu River, Japan’s aggressive approach proved successful against the European power that had hunkered down as they awaited reinforcements from the West. As the first major land battle of the war, Yalu River proved Japan would not be easily defeated and was a milestone victory of an Asian nation over a European power.

Ogata Gessan (1887–1967). Our Army Crosses the Yalu River on the Pontoon Bridge and Drives Back the Enemy Forces to Finally Occupy Jiuliancheng, 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.031)

Ogata Gessan (1887–1967). Our Army Crosses the Yalu River on the Pontoon Bridge and Drives Back the Enemy Forces to Finally Occupy Jiuliancheng, 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.031)

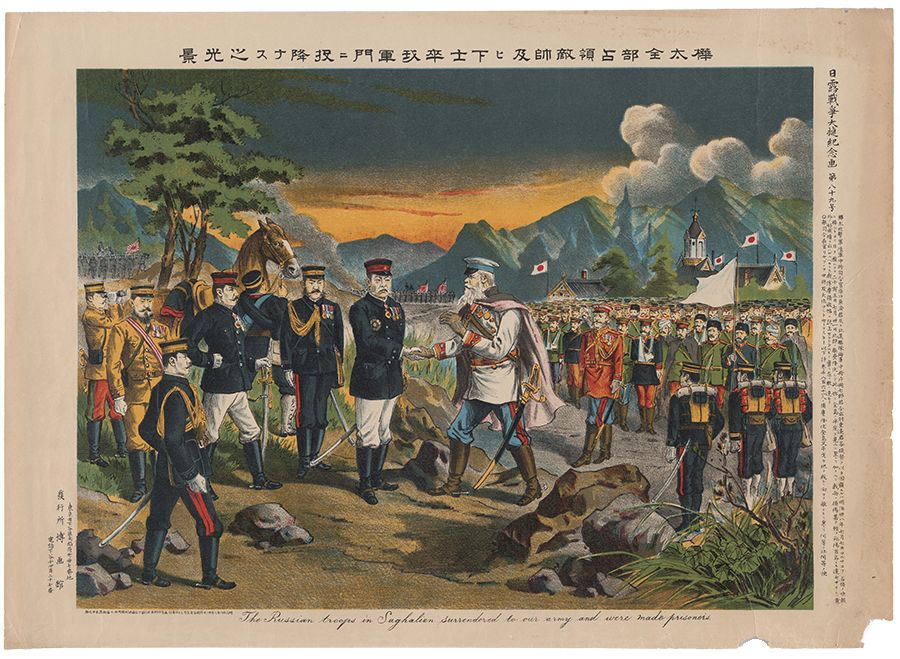

The success mobilized Japan’s army to take the bold move of landing troops north of Port Arthur on the Liaodong peninsula. The Japanese victory at the Battle of Nanshan in May, both isolated the Russians defending Port Arthur and enabled the Japanese Imperial Army to begin a push north into Manchuria. The reality of a Japanese overall victory became imaginable once Port Arthur fell in January 1905. The Russian retreat from Mukden later in March then heralded their defeat on land. Only the impending arrival of the Russian Baltic Fleet remained a threat to Japan. The fleet’s arrival in the region after the fall of Port Arthur left only the port of Vladivostok as a safe haven and resulted in their route through the Tsushima Straits. Awaiting them, however, was Admiral Tōgō and the Japanese Combined Fleet in Busan (southern Korea) from which they launched an annihilating attack. The Russian fleet was decimated and though overall defeat was apparent, it was not until the subsequent Japanese occupation of Sakhalin island in July that Russia requested peace.

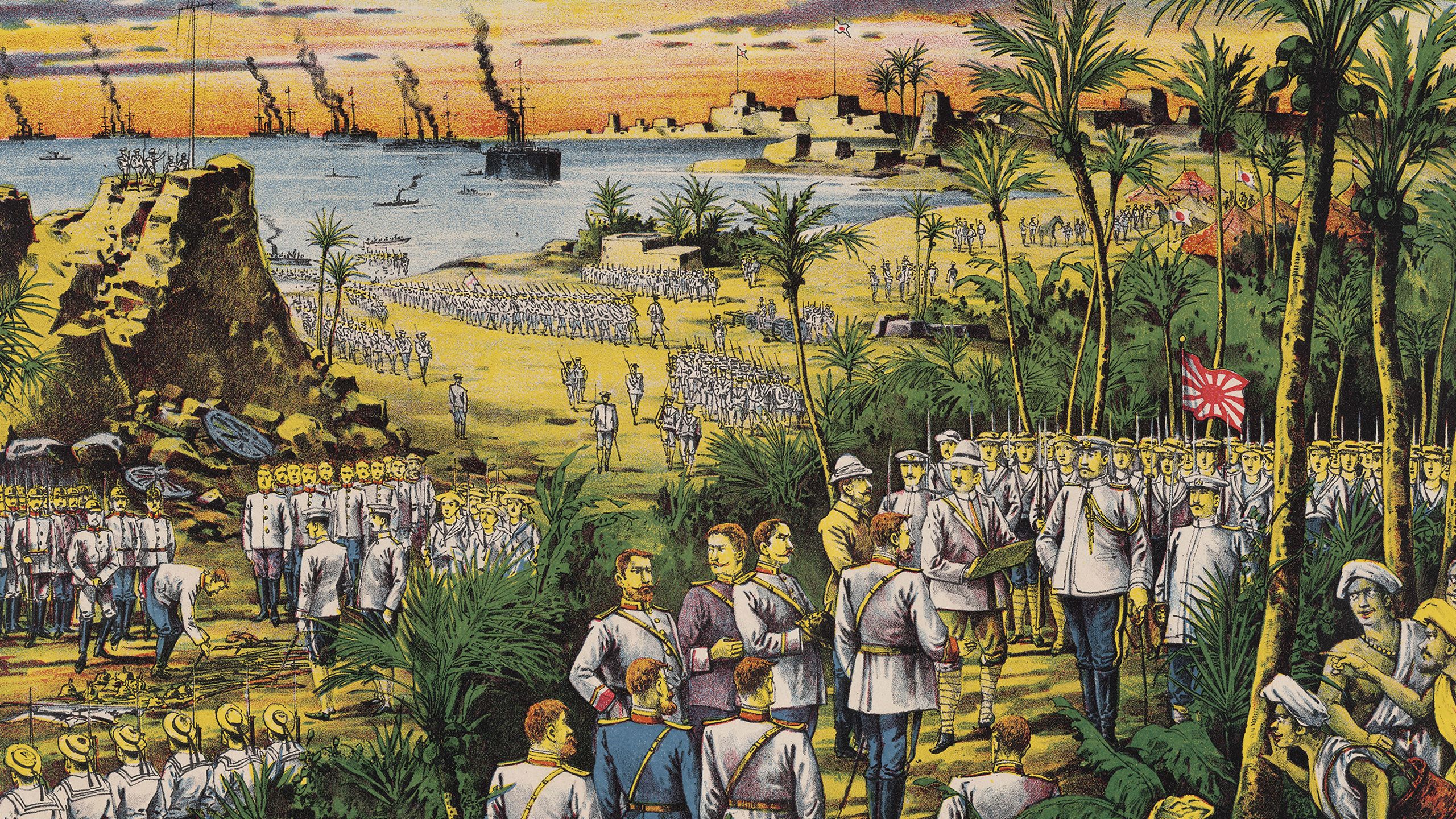

The Russian troops in Saghalien [sic] surrendered to our army and were made prisoners, 1905. Chromolithograph. Poster Collection JA 153, Hoover Institution Archives

The Russian troops in Saghalien [sic] surrendered to our army and were made prisoners, 1905. Chromolithograph. Poster Collection JA 153, Hoover Institution Archives

Although Russian military forces far exceeded those of the Japanese, both countries had to reach far into their coffers. Japan spent six times more on military expenses than it had during the First Sino-Japanese War and sourced about 40 percent of the total cost of 1.82629 billion yen from overseas bond issuances, backed by tariffs and the government’s tobacco monopoly sales revenue. The financial and human burden borne by the Japanese was then made heavier when the terms of the Treaty of Portsmouth did not meet the populace’s expectations—especially the lack of Russian financial reparations. As peace arbiter, the United States unwittingly planted a seed of distrust and contempt among the people of this rising Asian power.

Background Image: The scene of the fiercest fightings and the Burning of the Railway station at Mukden by our bombardment, March 9th, 1905 [sic]. Chromolithograph. Poster Collection JA 22, Hoover Institution Archives

Timeline of Major Events

Map with Major Battle Sites

| World War I

1914–1917

A critical period for world propaganda and a period in which Japan gained even greater international importance as a member of the Allied Forces, the Japanese military had minimal participation in the conflict. At the outbreak of war in 1914 Europe, Japan united with their longtime ally Britain largely in hopes of seizing German held territories in the Pacific. Quickly, the Japanese Imperial Navy took control of the Mariana, Caroline, and Marshall Islands, and German New Guinea with little resistance. They then targeted German-leased territories in China as well, including Shandong province and the area of Tsingtao. As Japanese ambition grew in China, so too did British and American wariness of their intentions. By the end of the war Japan’s seizure of former German-controlled territory won diplomatic recognition and their position among the leaders of the Paris Peace Conference led to a permanent seat on the Council of the League of Nations. Even though the Japanese sponsored racial equality amendment to the Treaty of Versailles failed, Japan was still in a much more powerful position internationally by the end of the war.

Background Image: The Illustration of the Great European War, No. 28. The Japanese Navy accepted surrender of the Yaluit Island Marshall Group in South Sea [sic], October 25, 1914. Chromolithograph. Poster Collection JA 31, Hoover Institution Archives

| The Interwar Period

1919–1941

Even before 1920, key Japanese industries had grown dependent on Chinese labor, resources, and markets for their economic well-being. So much so, prominent geopoliticians of the age thought that Japan’s future prosperity rested on its ability to control continental East Asia through stunting China’s rise and hastening the decline of the Western powers in the region. Japanese economic insecurity and cultural chauvinism too often assumed the form of ham-fisted diplomatic policies that periodically elicited Chinese outrage, resulting in several short-lived boycotts of Japanese goods and services.

Sino-Japanese relations soured again in 1931. The trigger event this time was the Wanpaoshan affair, a minor dispute between Korean and Chinese farmers. According to a source forwarded by the League of Nations, “127 Chinese were massacred and 393 wounded.” Chinese leaders blamed the Japanese government for failing to protect lives and property, giving them justification for yet another anti-Japanese boycott. Then, in September 1931, the Japanese Kwantung Army seized Manchuria (northeast China today) in what is now referred to as the Manchurian Incident. The Japanese business community panicked when Chinese employees walked off their jobs in protest and Shanghai businessmen refused all commercial transactions with them. Factory production halted. Unsold goods collected dust on store shelves. Cargo ships sat at anchor. Industries in Japan itself were slowly starved of raw materials. The Osaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry claimed the ongoing boycott was “tantamount to an act of war.”

In Shanghai, the reservoir of social tensions spilled over into violence. Each side blamed the other. Japan dispatched troops to Shanghai “to ensure the safety of [Japanese] residents” and demanded redress of various grievances.¹⁵ The situation deteriorated into a five-week-long armed conflict between the Empire of Japan and the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China. Most historians call it the Shanghai Incident or the January 28 Incident. The total number of combatants exceeded a hundred thousand men by accepted estimates. The city’s international residents watched the fighting from their homes and places of business; in a sense, the world had a front-row seat to the conflict.

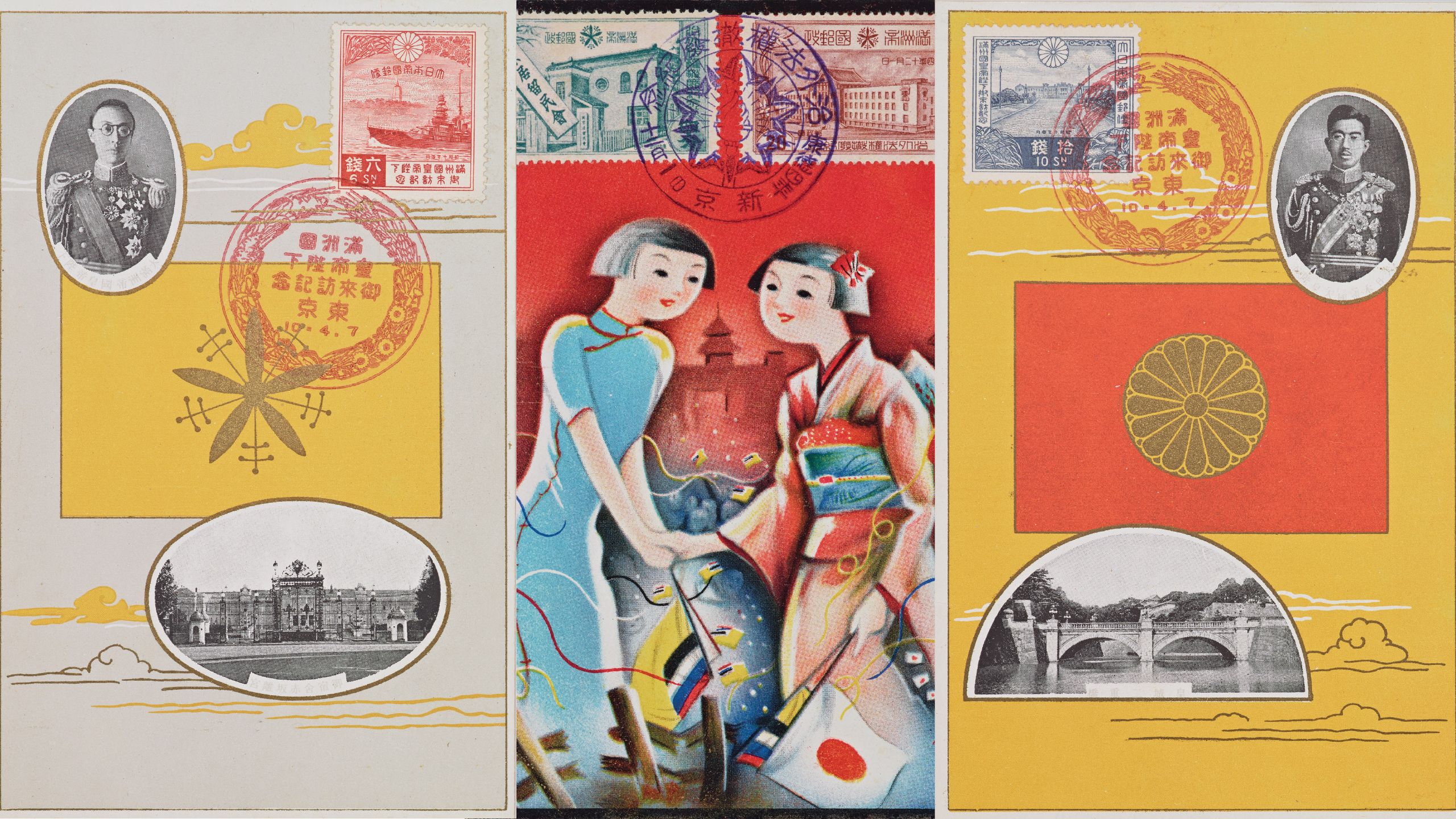

The international communities’ disapproval of Japan’s actions in Manchuria and retaliation in Shanghai did not derail Japanese ambitions, however. After much condemnation, in March 1932, the State of Manchuria adopted the moniker of Manchukuo with the former emperor of China, Puyi, as head of state—but with Japan acting as puppet master. When international recognition remained absent a year later, Japan resigned from the League of Nations. The Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang) had little choice in recognizing the new state in May 1933 when they signed the Tanggu Truce. No longer concerned with presenting as a nation on par with those of Europe, Japan became determined to show the world its might as a military superpower and its importance as an economic unifier in East Asia.

Background Image: Postcards commemorating the visit of the Manchukuo Emperor to Japan (photo of Emperor Aisin-Gioro Puyi inset at left and Emperor Meiji at right), 1935. Chromolithographs. Daniel K. E. Ching Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Second Sino-Japanese War

With the Chinese Civil War continuing to engulf the region in the 1930s, Japan bided its time as militant nationalism inflamed its people. Then in July 1937, the scales tipped and Japan officially invaded China. Initial success in seizing the areas of Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing, gave the Japanese confidence, however, the regrouping of the Chinese forces and eventual Japanese difficulties in administering and garrisoning seized territories led to a stalemate. Eventually, this regional conflict moved onto the international stage after the December 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, instigated the Pacific theater of World War II.

This introductory material includes passages originally published in Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan (2021) by contributors Michael R. Auslin, Toshihiko Kishi, Hanae Kurihara Kramer, Scott Kramer, Barak Kushner, Olivia Morello, and Kaoru (Kay) Ueda. We are most thankful for their permission to use the materials online.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team. For more information about rights and permissions please visit:https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.