War & Media in Modern Japan

The study of multiple types of graphic media over time allows us to better understand underlying themes and discover the uniqueness of Japanese propaganda at a given time as well as its continuity. The Fanning the Flames project intentionally spans the Meiji era through the Second World War for such an analysis. However, such a broad era of media, war, and propaganda means there are always further depths to explore. To better contextualize these investigations, the following sections highlight some of the major connections between war and the media in modern Japan.

I Newspapers in Meiji Japan

“War marked the beginning of the modern newspaper in Japan at the time of the Restoration, or the opening of the era of Meiji. Since then the newspapers have progressed by wars.”

— Frank L. Martin, The Journalism of Japan, 1918

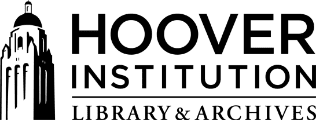

The era of peace that Japan experienced under Tokugawa had strengthened the national infrastructure and economy, making the country ripe for advancements in news media. Key to its growth was that Japan in the latter third of the nineteenth century was one of the more literate countries on earth. Already, news sellers catered to patrons eagerly awaiting penny broadsheets that combined often-sensationalized imagery—such as depictions of Commodore Perry’s fire-breathing steam vessels that arrived in 1853—with pithy news accounts.

A kawaraban (broadsheet) depicting one of Commodore Perry's black ships, 1853. Courtesy of Hachirō Yuasa Memorial Museum.

A kawaraban (broadsheet) depicting one of Commodore Perry's black ships, 1853. Courtesy of Hachirō Yuasa Memorial Museum.

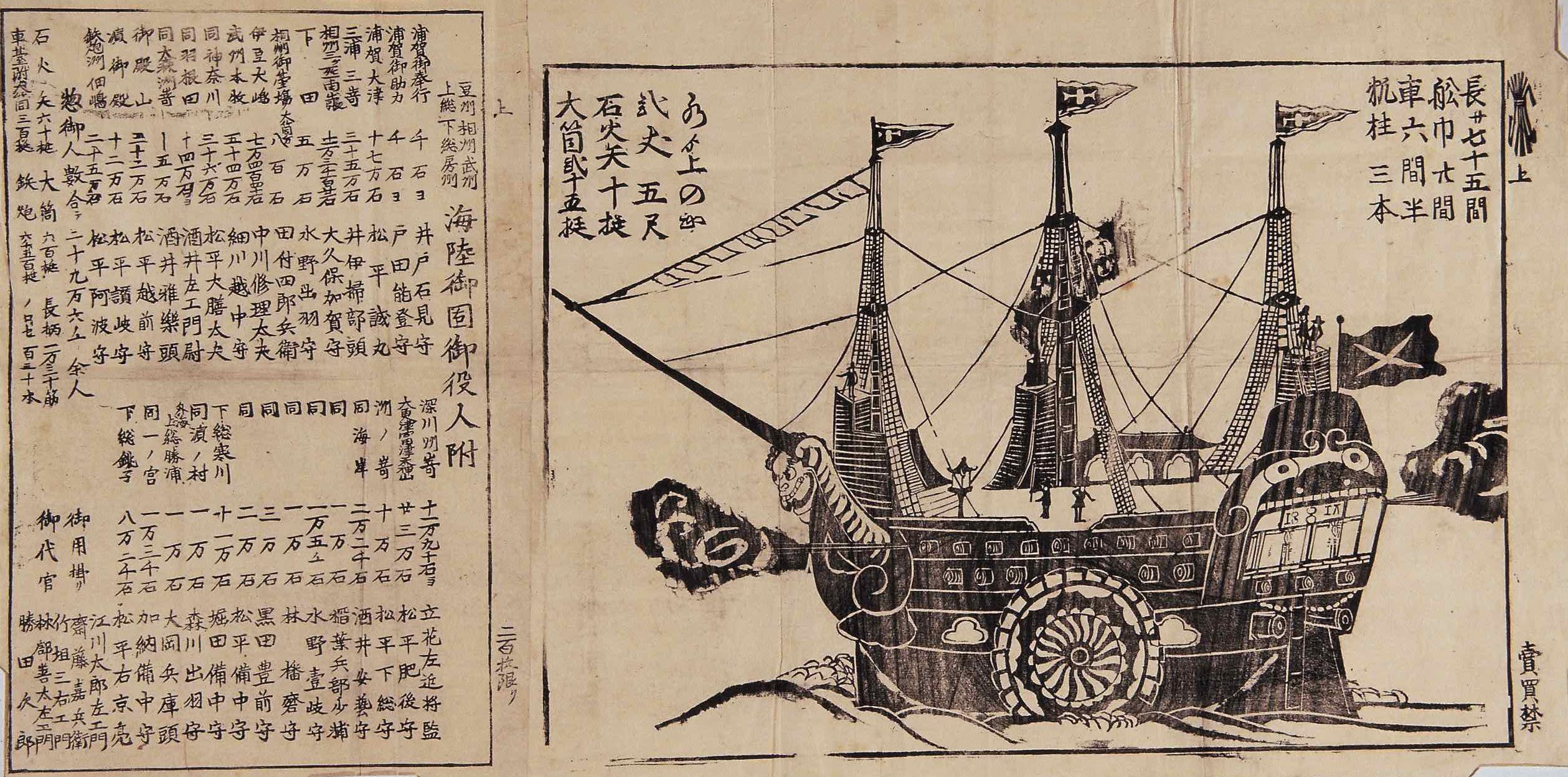

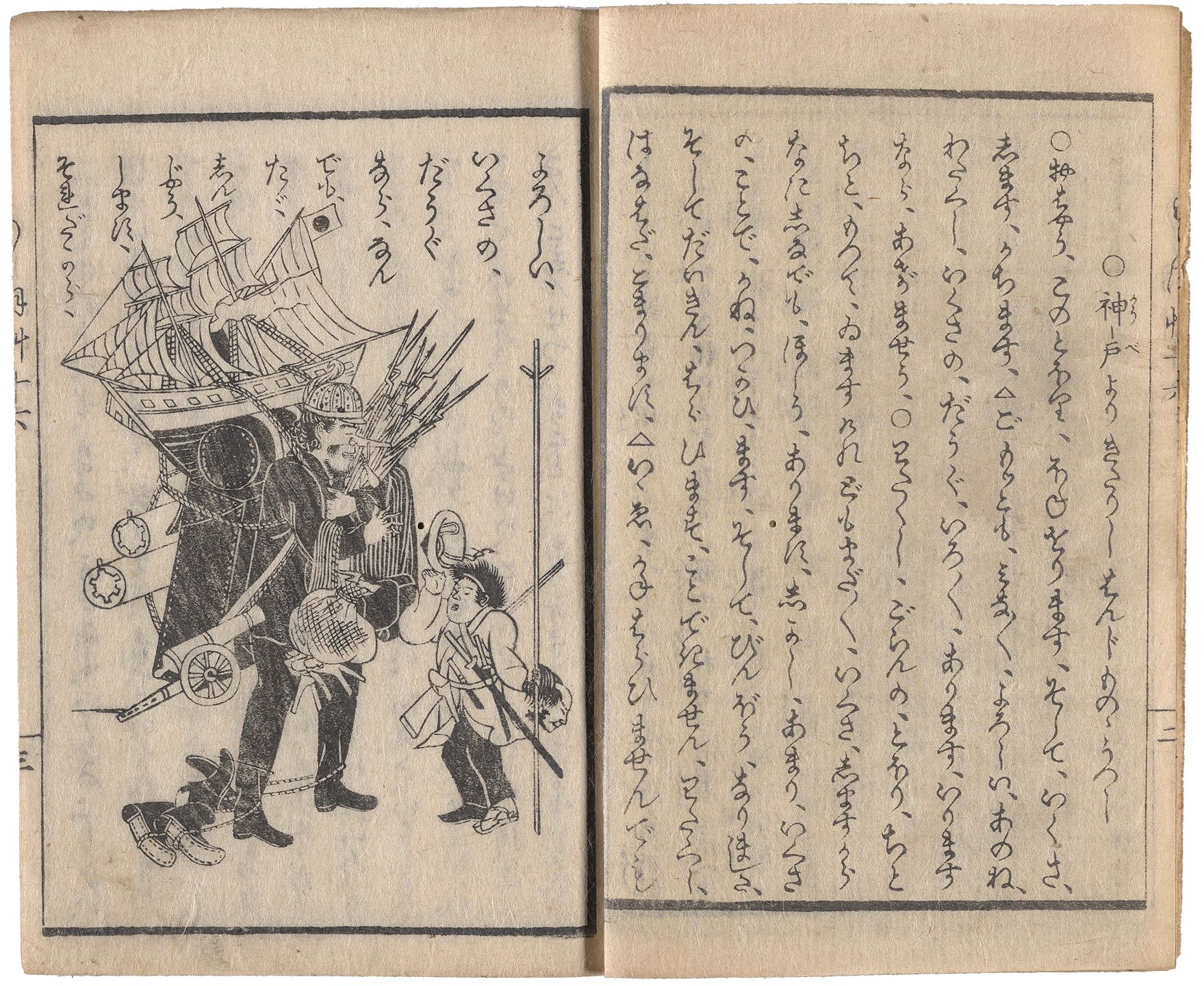

Several elements of the Meiji reformation, however, allowed news media to become mainstream. Censorship laws eased, allowing for the first time contemporaneous news to be published; Japanese printing techniques had evolved into high-level woodblock multicolor printing; compulsory education was established; and technological advances and methodologies from around the world entered the nation. Some of the earliest newspapers printed in Japan were published by Americans in the open port of Yokohama, where Westerners enjoyed extraterritorial privileges. Locals were soon to follow suit.

Cover and inside spread from the Yokohama shinpō moshihogusa, 1868. Woodblock-printed newspaper. Hoover Institution Archives (2017C50)

Cover and inside spread from the Yokohama shinpō moshihogusa, 1868. Woodblock-printed newspaper. Hoover Institution Archives (2017C50)

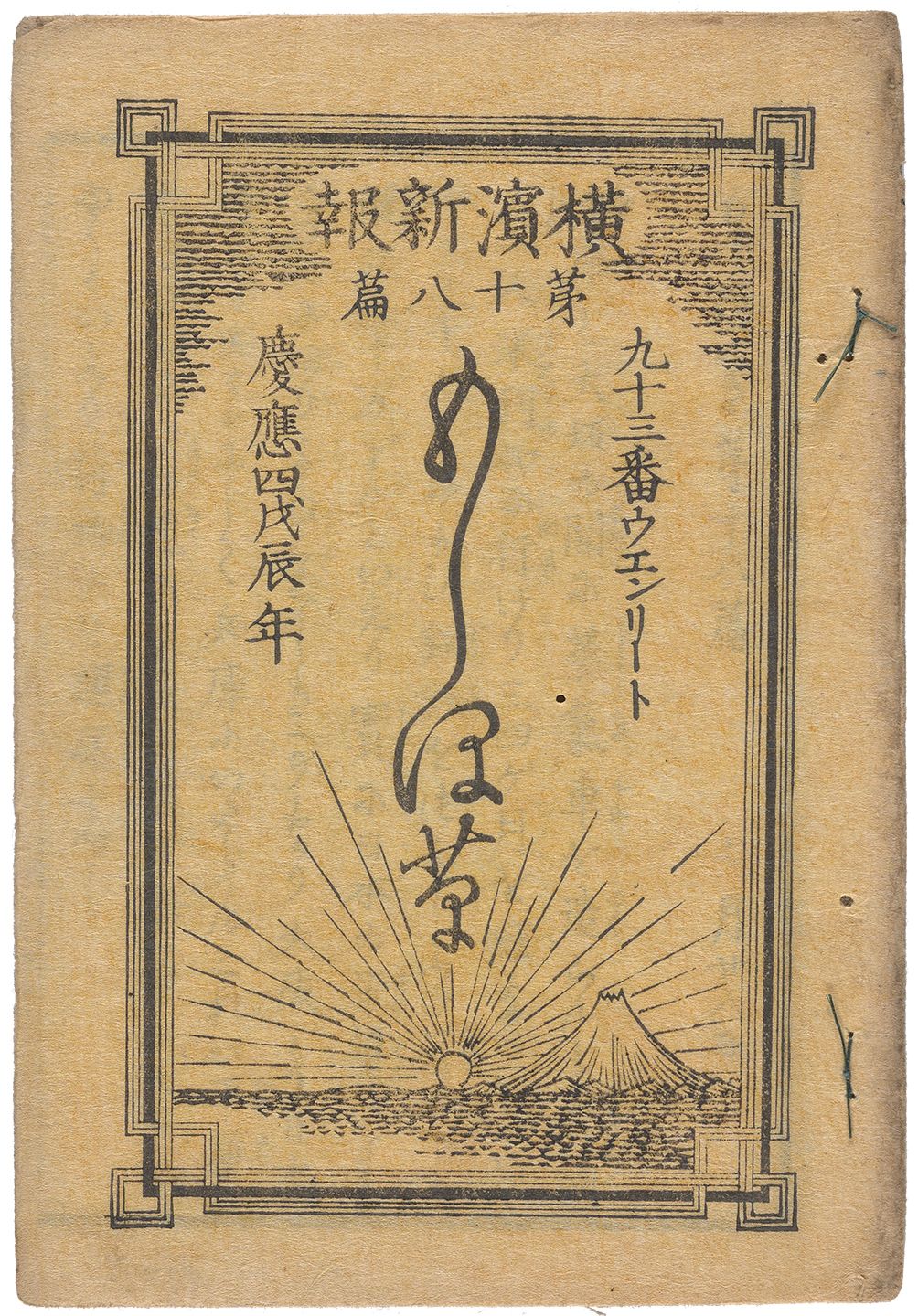

Joseph Heco (1837–97), a Japanese castaway and naturalized US citizen who became a translator at the US consulate, published the translated newspaper Kaigai shinbun in 1864. Eugene M. Van Reed together with Kishida Ginkō (1833–1905) issued one of the earliest Japanese newspapers, Yokohama shinpō moshihogusa, in 1868, featuring original content and reporting news in Japan and abroad. By 1873, records show 79 newspapers in service, a number that grew to 192 in the following six years—a surge in part attributable to the eagerness for news as the 1877 civil war, the Satsuma Rebellion, was waged.

A Hanjimono (Riddle) from Kobe, from the Yokohama shinpō Moshihogusa, No. 18, July 28, 1868. Woodblock-printed newspaper. Hoover Institution Archives (2017C50)

A Hanjimono (Riddle) from Kobe, from the Yokohama shinpō Moshihogusa, No. 18, July 28, 1868. Woodblock-printed newspaper. Hoover Institution Archives (2017C50)

Although movable-type presses had been introduced to Japan centuries earlier, by the Meiji era woodblock printing was deemed most effective for printing the cascading Japanese text. It wasn’t until the 1870s that mechanical printing presses from the West began to be used by newspapers like Tōkyō nichi nichi, Ōsaka Asahi, and Yomiuri. By the turn of the century, mechanical printing presses were churning out daily newspapers and publications throughout Japan, many beginning to feature reproductions of illustrations and photographs through the halftone process.

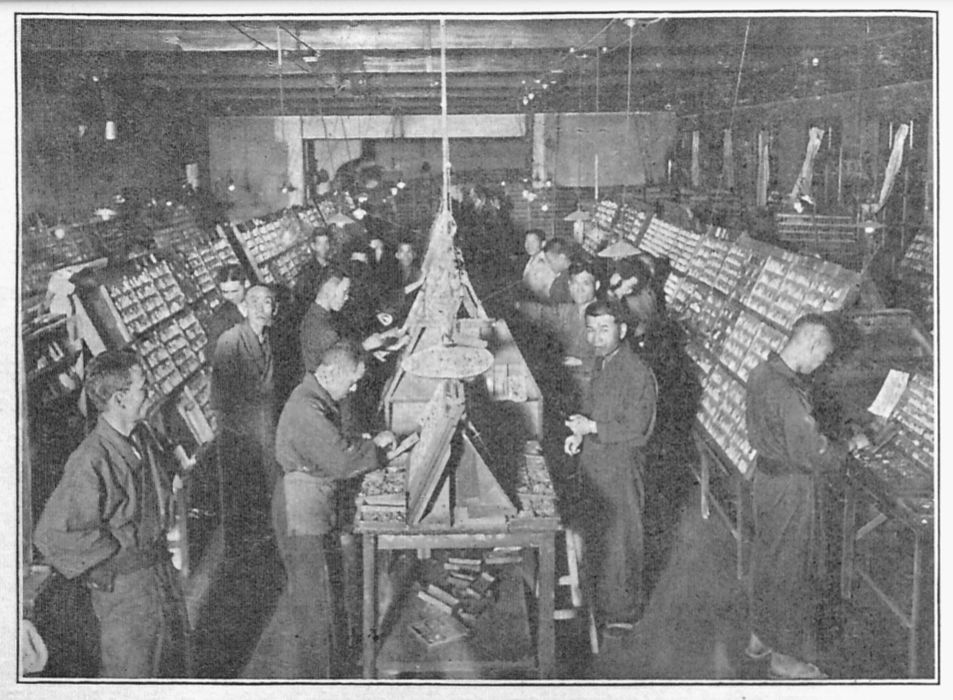

The composing room of the Asahi shinbun, Tokyo, from Frank L. Martin, "The Journalism of Japan," The University of Missouri Bulletin, vol. 19, no. 10, April 1918.

The composing room of the Asahi shinbun, Tokyo, from Frank L. Martin, "The Journalism of Japan," The University of Missouri Bulletin, vol. 19, no. 10, April 1918.

With the growth of news media came a rise in journalists. For the first few decades of the Meiji era, the government was the single largest source of the news. Reporters were dispatched daily to government agencies to collect and disseminate official reports. This tacit control by the government unsurprisingly meant that the first correspondents abroad were approved by official government parties and accompanied them. In 1872, a member of Prince Iwakura’s entourage was engaged by the Tōkyō nichi nichi to send home stories about their trip to the United States. The 1874 Taiwan expedition was accompanied by Japan’s first war correspondent, Kishida Ginkō, who wrote the series “News from Taiwan” (Taiwan shinpō) also for the Tōkyō nichi nichi. Unforeseen newsworthy events overseas were thus reliant on official government reports—such as Minister Hanabusa Yoshitada’s telegrams to Minister of Foreign Affairs Inoue Kaoru during the Imo Incident of 1882, which were printed verbatim or in conjunction with minutes from ministerial meetings.

I First Sino-Japanese War Media

Even while facing censorship, the Meiji era saw a growing public demand for journalism and news media. Reporting contemporary events was a fresh venture for Japanese journalists and nishiki-e artists alike, and Japanese consumers demonstrated a strong appetite. James Huffman argues that the First Sino-Japanese War redefined Japanese journalism and helped Japanese journalists form three central ideas: that news was central to journalism, that support for Japanese overseas expansion was paramount, and that readers’ demands should drive content. Newspapers, strictly watched by the Japanese government, played a significant role in providing nationalist rhetoric and a timely reporting of battles to ordinary Japanese. Photographs were not yet the mainstream visual media used in newspapers, although illustrations using the newly introduced Western techniques of lithography and halftone printing started making inroads into the press, eventually causing the decline of woodblock prints. Woodblock prints, affordable to most Japanese even at the lower rungs, had been widely distributed and filled the gap in reportorial coverage by satisfying the public’s visual curiosity.

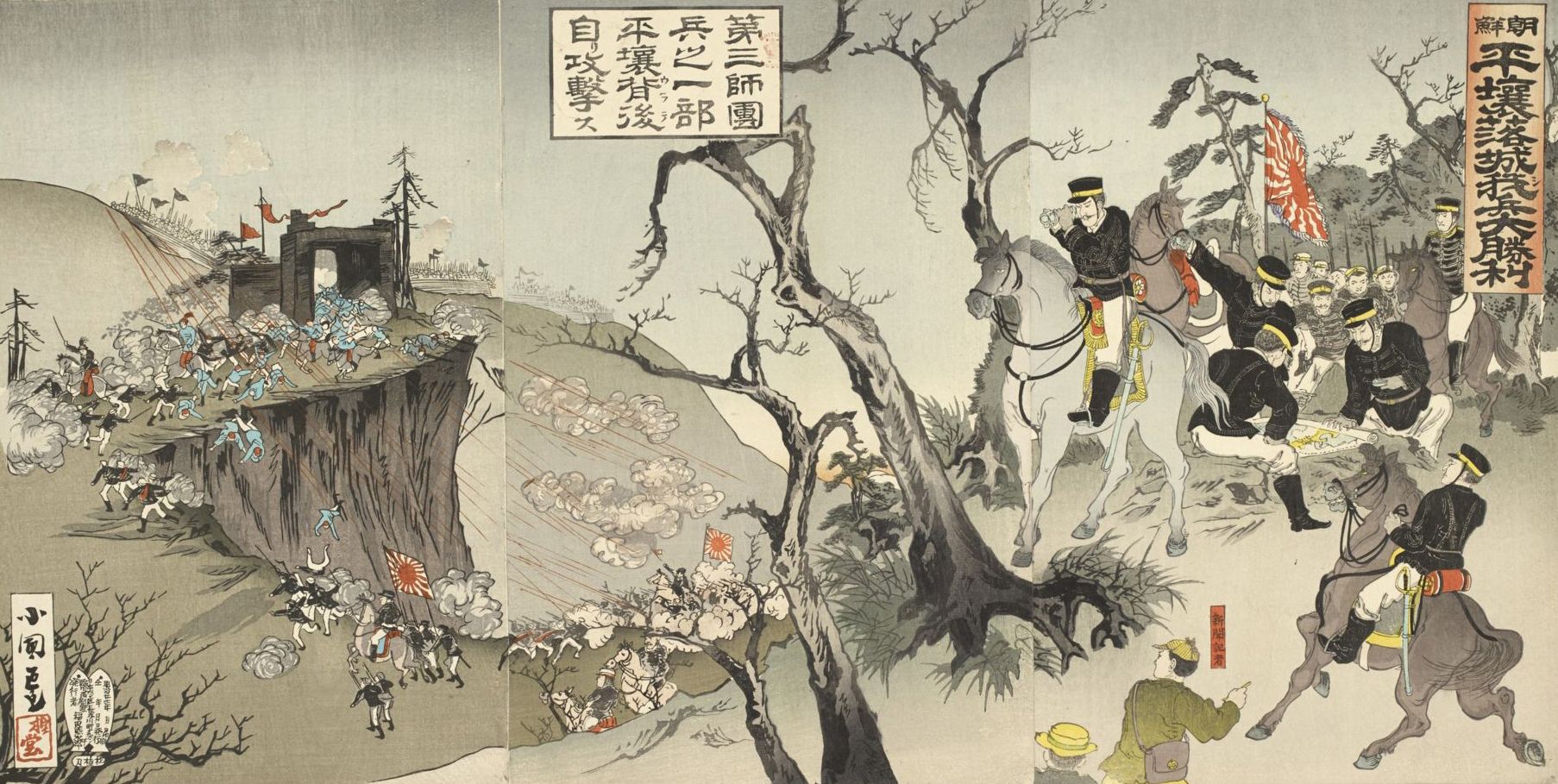

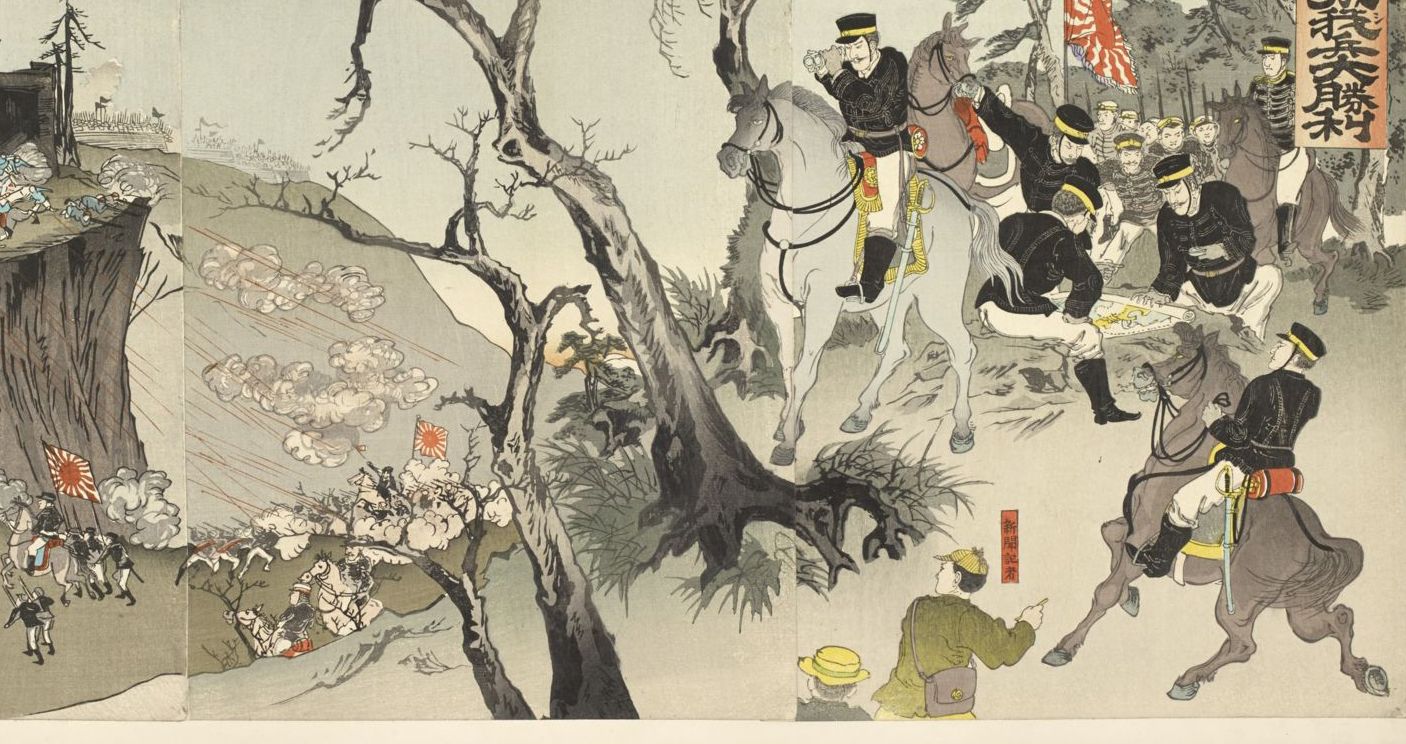

One hundred fourteen members of the Japanese press, eleven artists, and four photographers accompanied the Japanese Army for about one year from July 1894. The Jiji shinbun newspaper dispatched a “visual” team consisting of painters like Asai Chū, Anzai Naozō, Asai Kaiichi, and photographers. Its rival paper, Kokumin shinbun, sent Japanese painters including Kubota Beisen and his sons, Beisai and Kinsen. Journalists and artists even made appearances into Japanese nishiki-e (multicolored woodblock prints). The woodblock artist Kokunimasa (Utagawa Kunimasa V, 1874–1944) depicted two newspaper reporters in Chōsen Heijō rakujō wagahei daishōri (Our great victory: The fall of Korean Pyongyang castle), 1894 (image below).

Courtesy of the British Library (16126.d.2(86))

Courtesy of the British Library (16126.d.2(86))

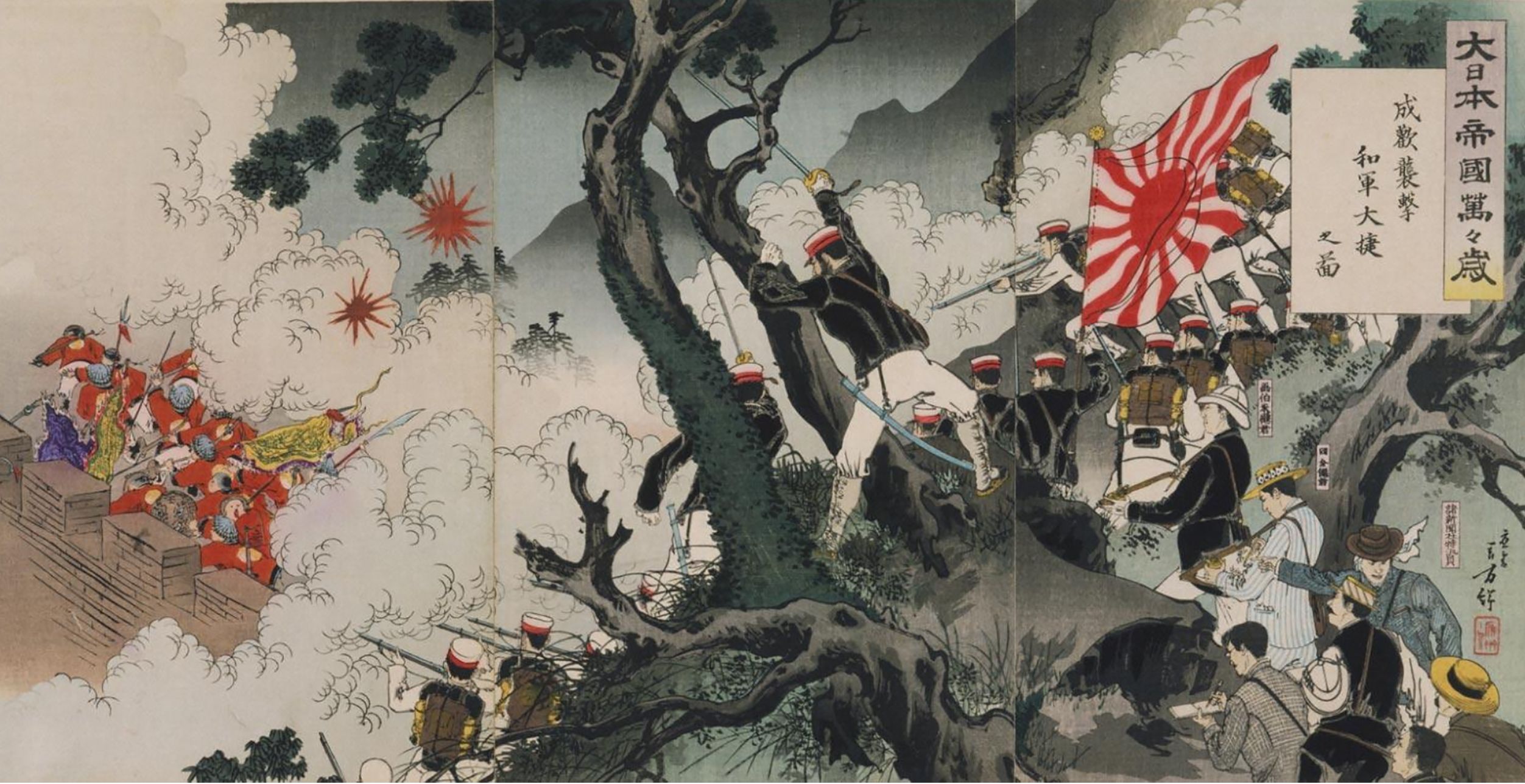

Mizuno Toshikata (1866–1908) illustrated a painter in Dai Nippon teikoku ban banzai: Seikan shūgeki wagun taishō no zu (An attack on Seonghwan and banzai to the great Japanese empire), January 8, 1894 (image below).

Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (2000.435a-c)

Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (2000.435a-c)

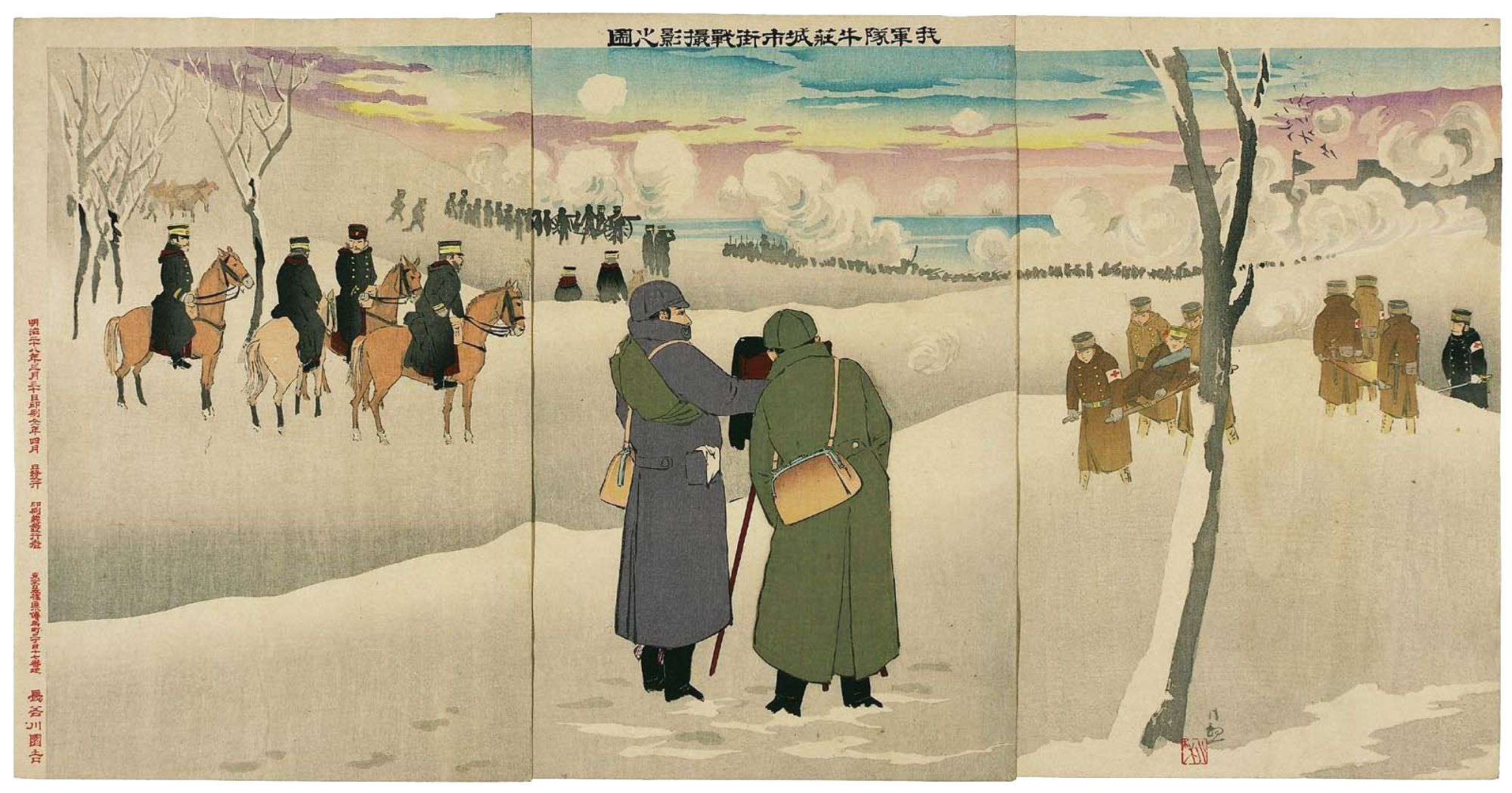

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915) did not forget to illustrate far fewer photographers in Waga guntai Nyūchanjō shigaisen satsuei no zu (An illustration of photographing a battle in the city of Niuzhuang), 1895 (image below).

Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (2000.473a-c)

Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (2000.473a-c)

Special correspondents were also dispatched from Europe and America. Illustrated London News, known as the first illustrated newspaper, featured a foreign journalists’ dining scene lithographed by Richard C. Woodville Jr. (1856–1927) on September 29, 1894.

Walter Gifford Smith (San Francisco Chronicle correspondent) Wartime Notes, 1894-95. Hoover Institution Archives (99045)

War fever was initially limited to the elites. Only former samurai enthusiastically viewed the First Sino-Japanese War as an opportunity to combat their depressive downfall, and intellectuals like Fukuzawa Yukichi and Uchimura Kanzō in Japan and pro-westernization Chinese officials were enamored with the war. The masses in both countries initially showed muted interest. The large-scale production of war nishiki-e and photographs, made possible by the development of printing techniques like lithography, collotype printing, and photoetching, inundated the market and swallowed the masses into war fever. In Japan, nishiki-e became fashionable again as if beaming in its last moments of glory. Nisshin sensō jikki (True accounts of the Sino-Japanese War), featuring the rising media of photographs, had record sales. In China, Dian shi zhai hua bao, a lithographic magazine, introduced the new nineteenth-century technique of lithographs and swept the Qing world. Against the backdrop of fashionable Japonism, Western nations showed a strong interest in the war, which occurred only ten years after the Sino-French War. They, too, illustrated the war with distinct visual media, using new plate-making and printing techniques.

I Russo-Japanese War Media

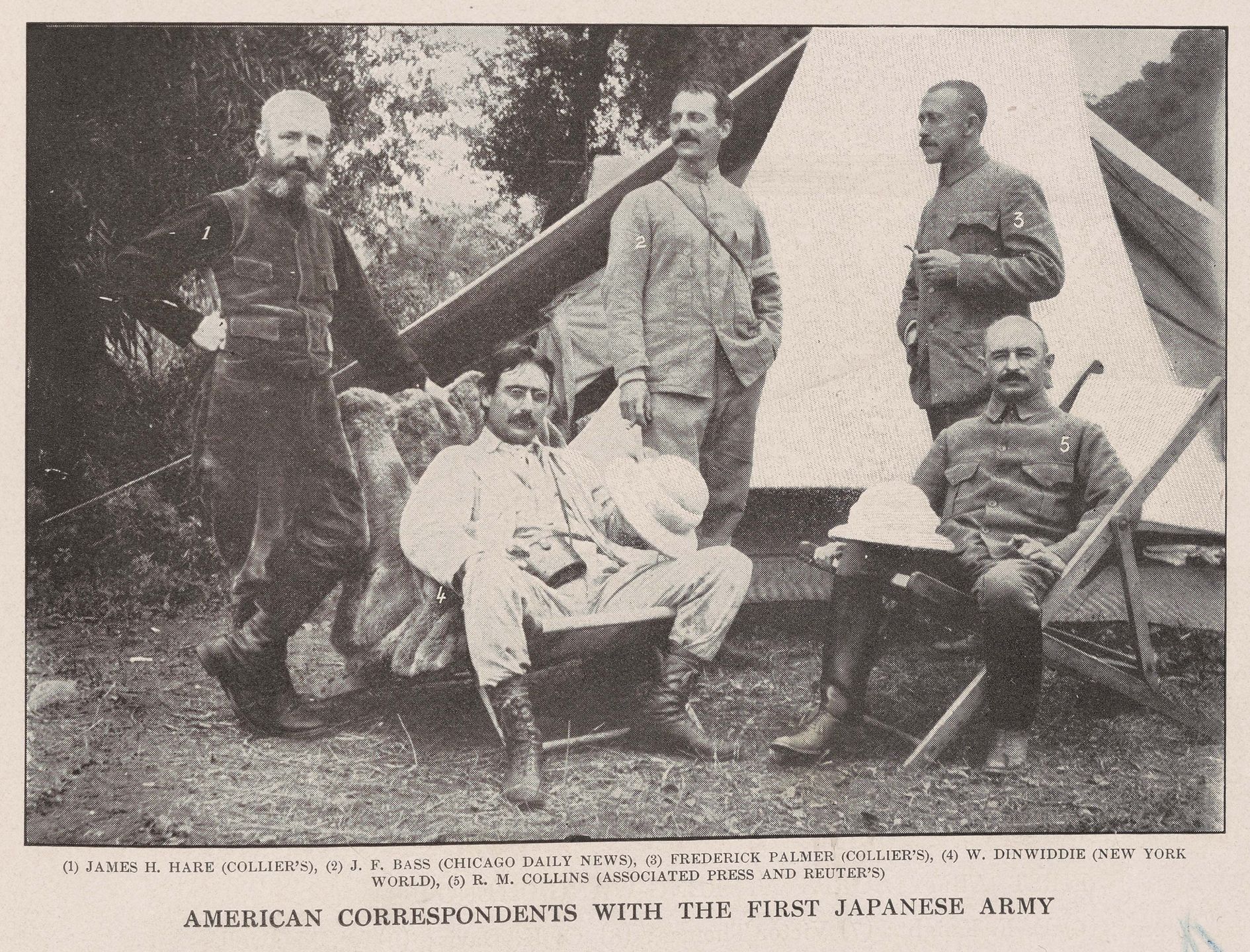

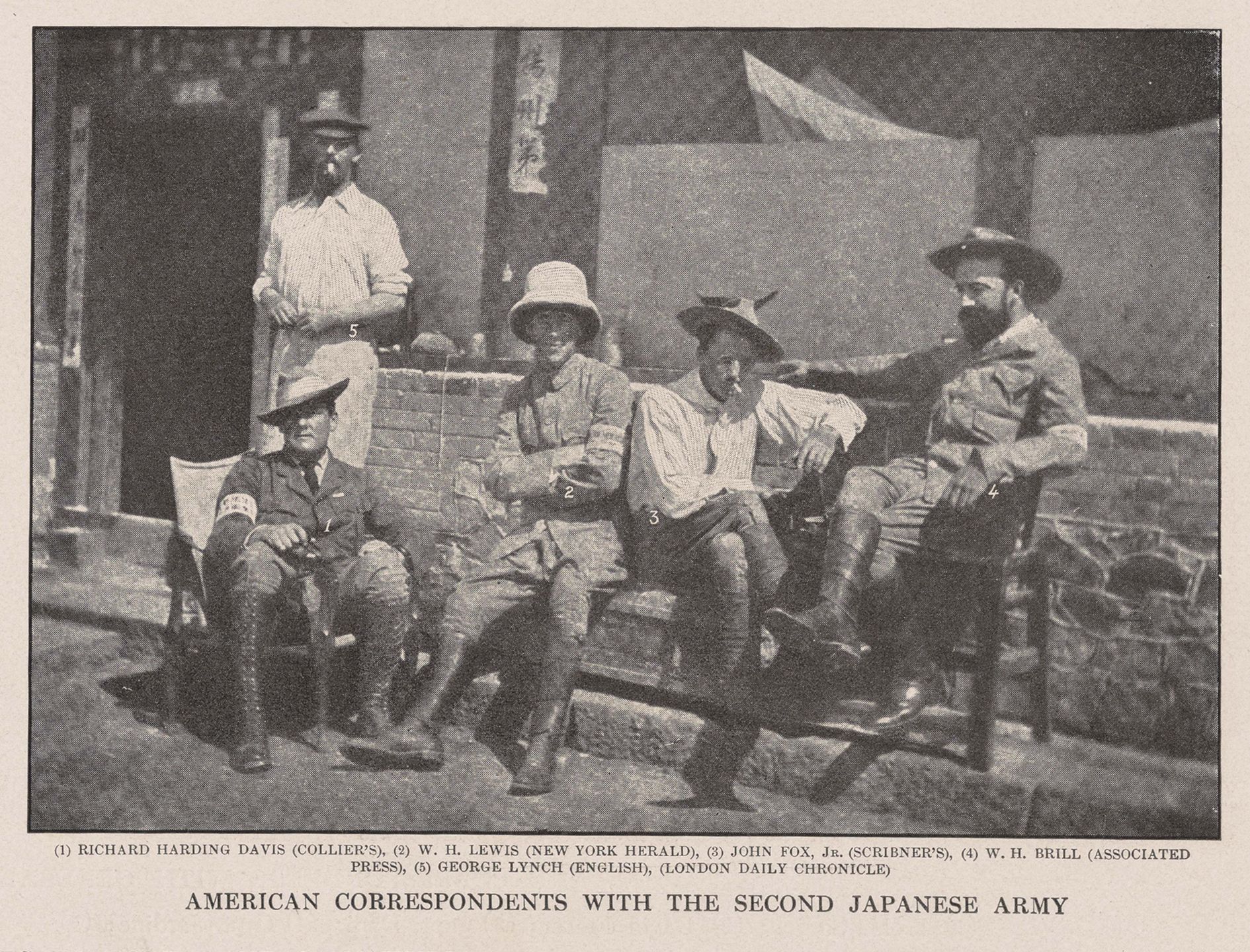

Fighting for the first time against a major Western power, Japan sought to promote itself both domestically and abroad as a civilized modern nation deserving respect from the international community. To mobilize international and domestic support during the conflict, the Japanese understood the need to control both their own press and the foreign press. The Russo-Japanese War attracted hundreds of foreign observers and dominated the international media. Once foreign reporters arrived in Japan, however, Japanese authorities subjected them to strict censorship. Access to the front was extremely limited. Those few foreign correspondents who did receive permission to travel with the military to the front lines were not allowed to go close to soldiers during the action, and their press dispatches were heavily censored.

American Correspondents embedded with the Japanese Imperial Army in Korea and Manchuria, ca. 1904–05. From page 199 in A Photographic Record of the Russo-Japanese War (1905). Hoover Institution Library (DS517.9 .H2 1905 F)

American Correspondents embedded with the Japanese Imperial Army in Korea and Manchuria, ca. 1904–05. From page 199 in A Photographic Record of the Russo-Japanese War (1905). Hoover Institution Library (DS517.9 .H2 1905 F)

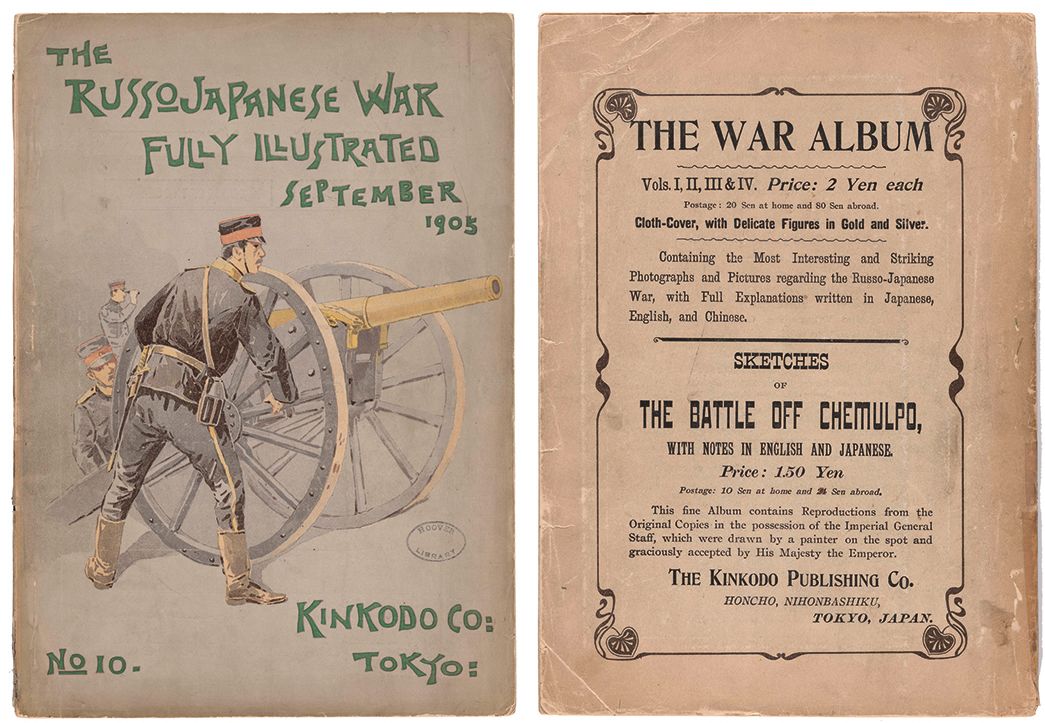

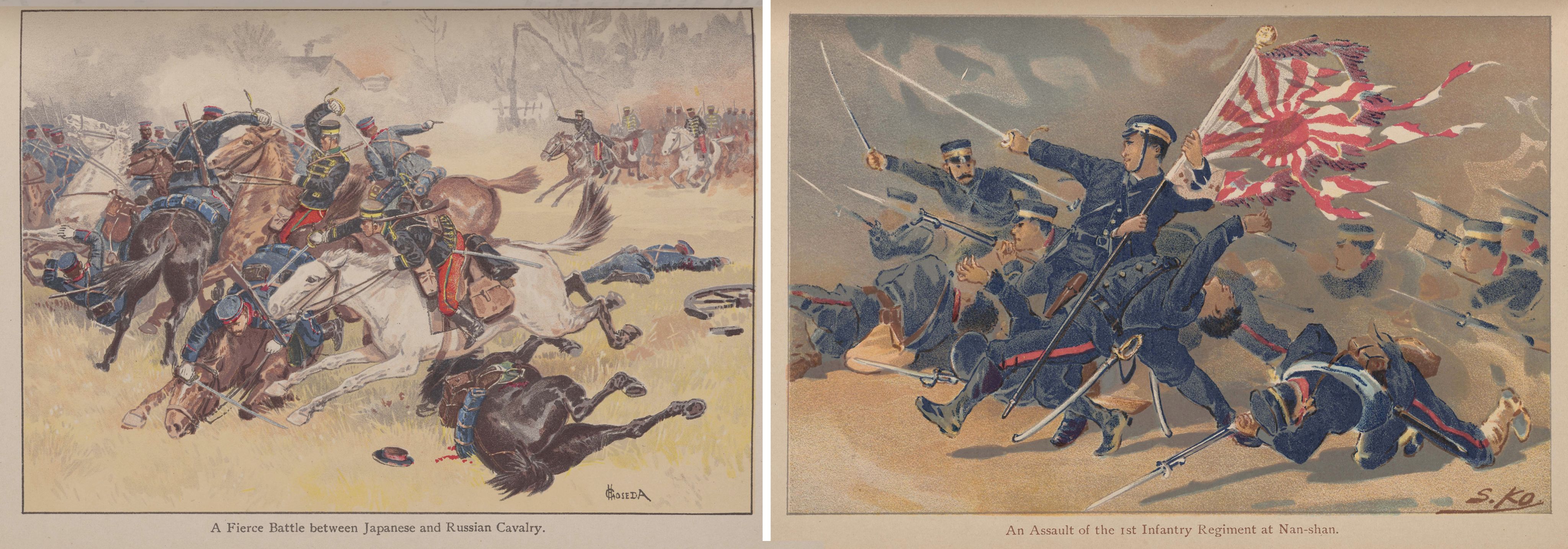

Japanese newspapers, while still subject to strict censorship, also played an important role in influencing both domestic and international public opinion. Aggressive and incredibly nationalistic, most Japanese newspapers sent correspondents, artists, and photographers to the front as soon as war was declared. Japanese editors knew their greater access to timely news from the front would lead the foreign press to disseminate their stories in an eager attempt to satiate worldwide demand, even though those stories remained primarily targeted at the domestic market. Special publications devoted to the war, like that of Senji gahō and Nichi-Ro sensō shashin, were in Japanese but included captions in English. The Japanese publishing company Kinkodo directed its products and its war publications specifically toward the English-speaking market.

Covers from The Russo-Japanese War Fully Illustrated, No. 10. Tokyo: Kinkodo Co. 1905. Hoover Institution Library (DS517 .A1 R96)

Covers from The Russo-Japanese War Fully Illustrated, No. 10. Tokyo: Kinkodo Co. 1905. Hoover Institution Library (DS517 .A1 R96)

An Assault of the 1st Infantry Regiment at Nan-shan. From The Russo-Japanese War Fully Illustrated, No. 3, Tokyo: Kinkodo Co. 1904. Hoover Institution Library (DS517 .A1 R96)

An Assault of the 1st Infantry Regiment at Nan-shan. From The Russo-Japanese War Fully Illustrated, No. 3, Tokyo: Kinkodo Co. 1904. Hoover Institution Library (DS517 .A1 R96)

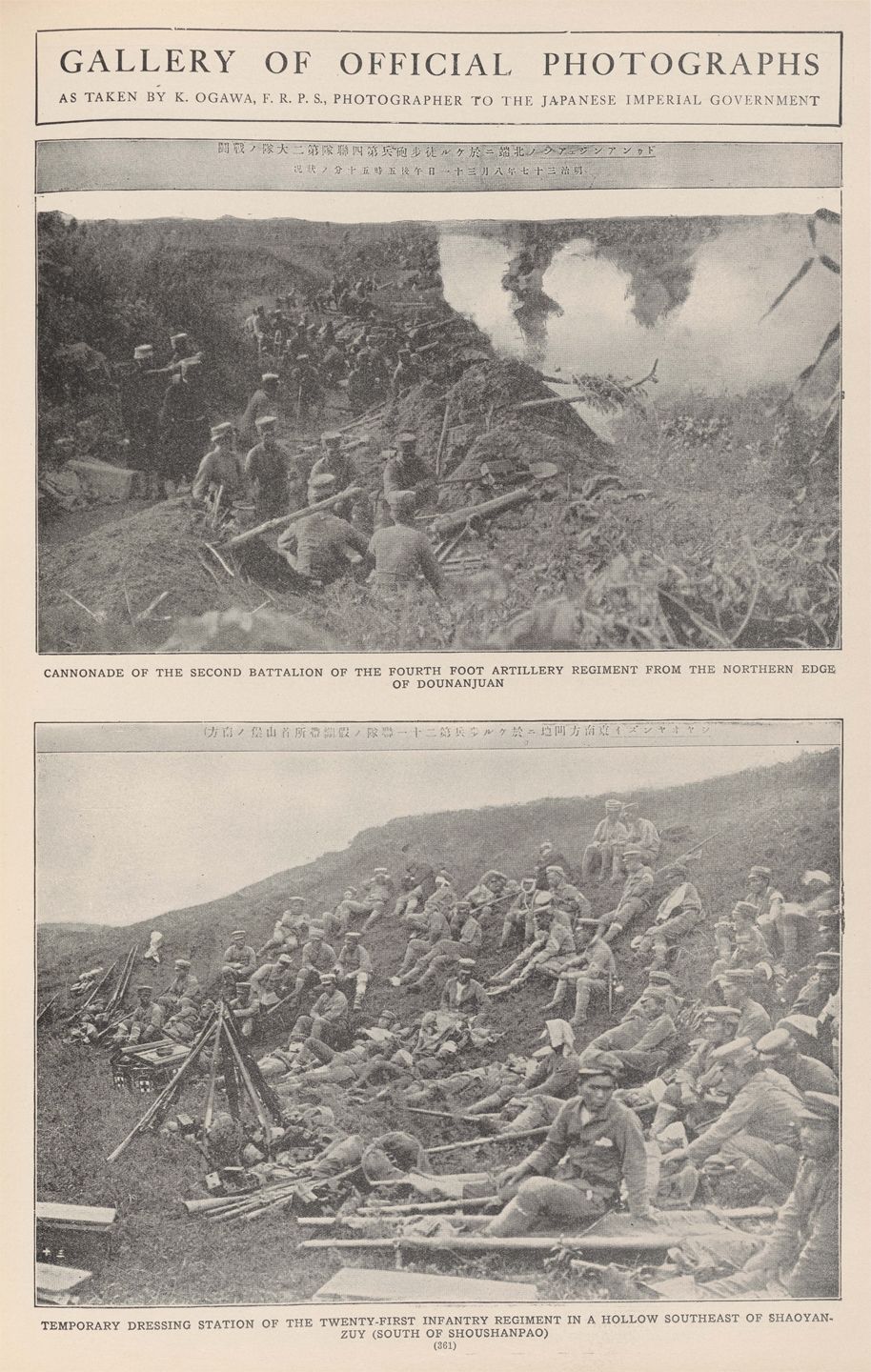

Japan also recognized that the rapid dissemination of visual propaganda in conjunction with these news reports would be crucial in gaining support from the Japanese public and foreign powers alike. The most common forms of graphic reportage used during the Russo-Japanese War, however, differed from those used during the Sino-Japanese War. Reliance on the woodblock print medium had diminished considerably in the years between the two conflicts. Innovations in lithography and photography led these media to be less expensive, and they gradually replaced nishiki-e as the most common forms of battlefield reportage and visual propaganda. Photographs had already become widely available in the newspaper and publishing industries.

Photographs by Ogawa Kazumasa (1860–1929), photographer to the Japanese Imperial Government, ca. 1904–05. From page 361 of Russia and Japan, including the Tragic Struggle by Land and Sea for Empire in the Far East (1906). Hoover Institution Library (DS517 .R85 F)

Photographs by Ogawa Kazumasa (1860–1929), photographer to the Japanese Imperial Government, ca. 1904–05. From page 361 of Russia and Japan, including the Tragic Struggle by Land and Sea for Empire in the Far East (1906). Hoover Institution Library (DS517 .R85 F)

Postcards and movies also played a large role in disseminating propagandistic imagery during the war. The famous woodblock artist Kobayashi Kiyochika, who was said to have designed more than seventy triptychs during the Sino-Japanese War, produced about twenty during the Russo-Japanese War.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915). Banzai Japan—One Hundred Selections, One Hundred Laughs: Miss Jiuliangcheng’s Fighting Spirit, June 20, 1904. Ōban woodblock print.Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.022)

This short film is a historical re-enactment of a naval battle in Chemulpo Bay off the coast of Korea during the Russo-Japanese war. Filmed by Edwin S. Porter for Thomas A. Edison, Inc. on April 18, 1904 in the Edison studios, New York, N.Y. It is one of several films they made about the war, demonstrating the widespread international interest in the conflict. Courtesy of the Library of Congress (mp73003400)

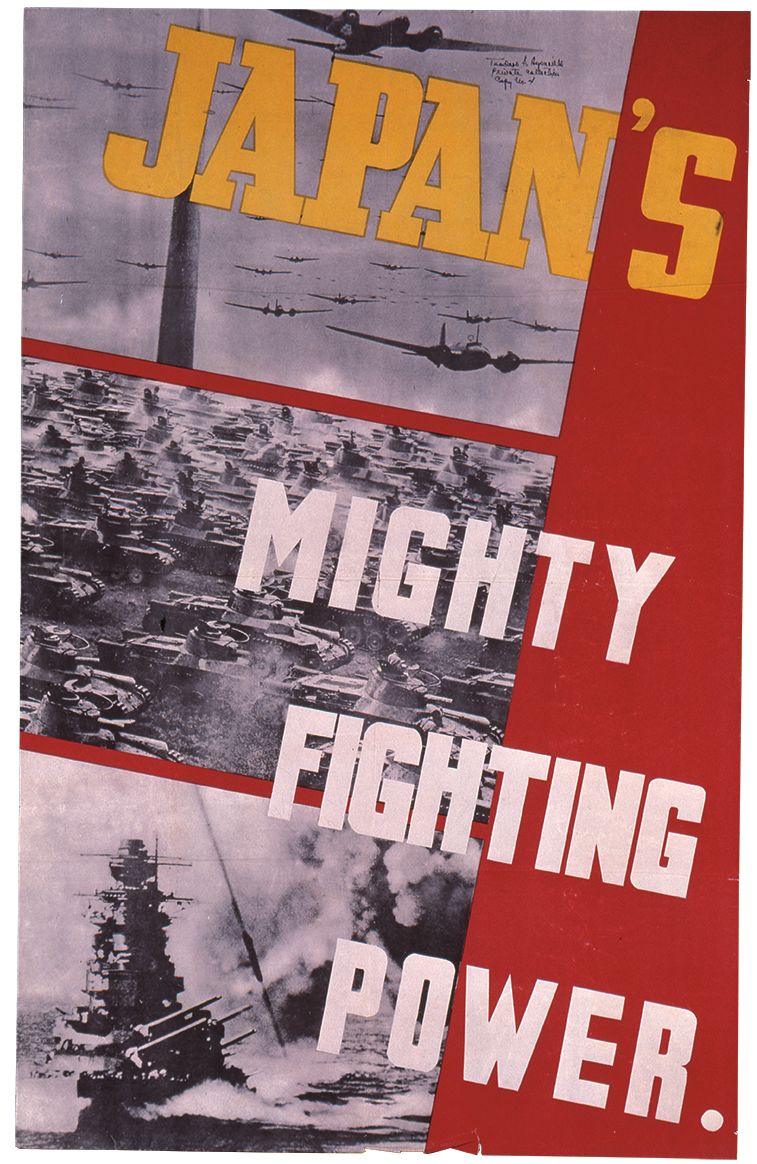

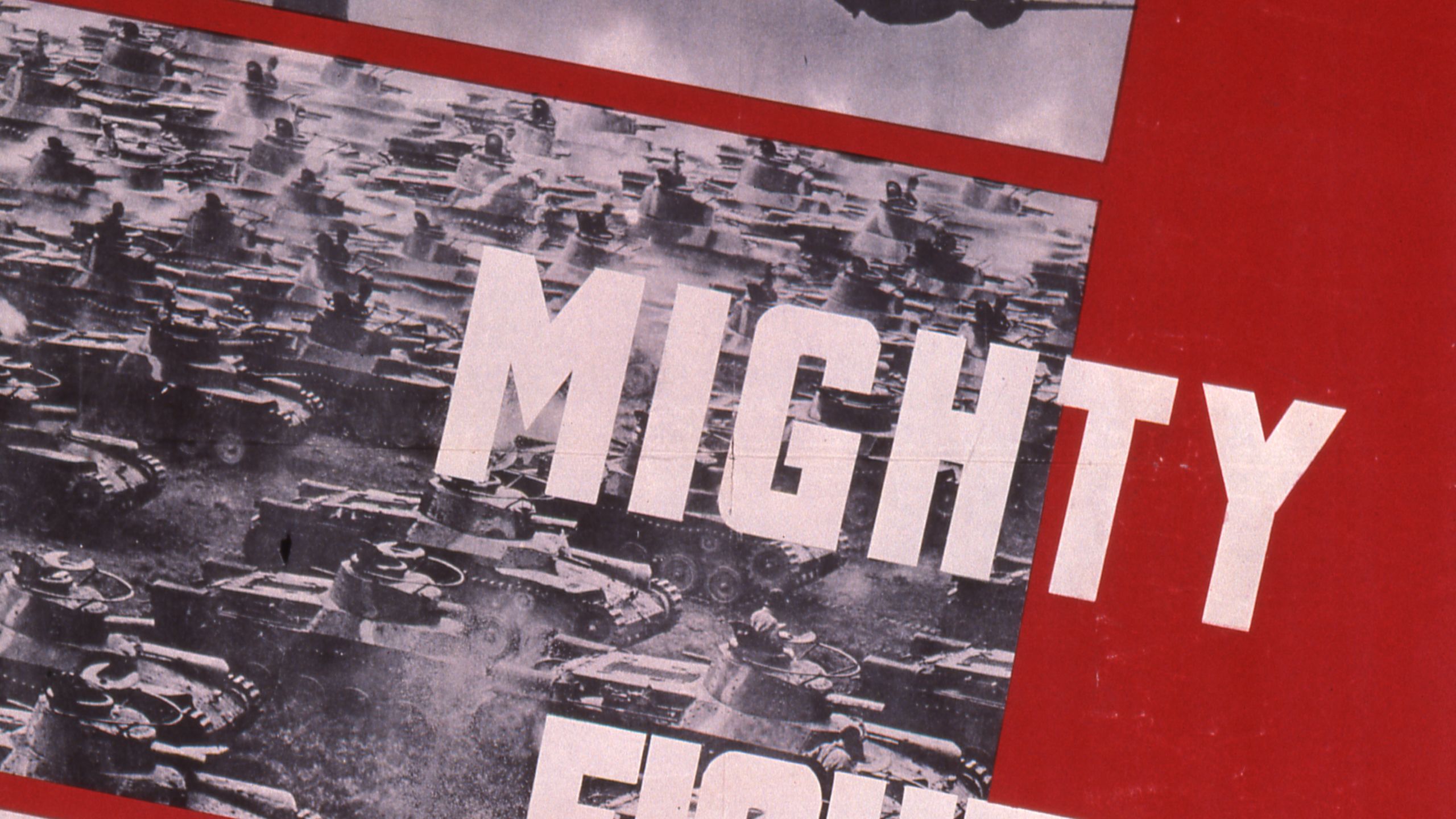

I Media during the Asia-Pacific War

By the 1930s, Japan’s well developed capitalist mass media industry was based on print media, film and radio. As war escalated, national mobilization created what is traditionally viewed as an oppressive period in which the state ruled over most aspects of daily life—including mass media—with strict controls, censorship, and the promotion of national sacrifice. At the heart of their messaging was the declaration that the nation of Japan was divine and protected by the gods. Yet the eventual deterioration of Japan’s position in the war by 1943 led to a decline in the government’s earlier intrusive cultural controls. The need became clear that raising public moral and wartime productivity through entertainment was paramount.

Similar to the war frenzy whipped up by the newspaper dailies during the Manchurian Incident (1931–32), the escalation of war in China in 1937 presented another opportunity to capitalize on sensational stories from the front—bringing in readers, boosting circulation, and showcasing the media’s sense of patriotic duty. Yet drastic censorship was quickly enacted by the government.

Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department Censorship Division, 1938. From Shashin shūhō 14, May 18, 1938. Courtesy of JACAR (Japan Center for Asian Historical Records), Ref. A06031060900, National Archives of Japan.

Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department Censorship Division, 1938. From Shashin shūhō 14, May 18, 1938. Courtesy of JACAR (Japan Center for Asian Historical Records), Ref. A06031060900, National Archives of Japan.

Article 27 of the Newspaper Law was put into effect, requiring government clearance to publish war related news. While other censorship policies carefully honed how the media should present the fighting and Japanese overseas in a positive and patriotic light to enhance national unity. In particular, one Home Ministry directive to local officials specifically banned the printing of “fallacies” that could “confuse the hearts of people and induce social unrest.”

These kinds of top-down policies, however, were not the sole methodology at play influencing news media during the war. Informal consultations and appeals from officials to the good graces of media companies were rampant and led to internally created guidelines and self-policing in the industry. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in reports such as the Army Ministry’s August 1937 assessment that eighty percent of articles were approved. An alarming statistic for the Home Ministry that was quickly explained as resulting from newspaper editors only submitting articles they believed would pass. There was little sympathy for accompanying photographs at the censors, however, as the power of images from the frontlines on the home front was considered far too influential.

Japan's Mighty Fighting Power, ca. 1945. Chromolithograph poster. Hoover Institution Archives (JA 92)

Japan's Mighty Fighting Power, ca. 1945. Chromolithograph poster. Hoover Institution Archives (JA 92)

This introductory material includes passages originally published in Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan (2021) by contributors Toshihiko Kishi and Kaoru (Kay) Ueda. We are most thankful for their permission to use the materials online.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team. For more information about rights and permissions please visit:https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.