National Policy Kamishibai

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) triggered earnest mobilization efforts. Street kamishibai performers flocked to the front line of national home front policies. The Japanese authorities initially did not regard kamishibai as influential in the war mobilization. Instead, they gradually acknowledged its role during screenplay censorship efforts (1937–April 1938) and with the establishment of the Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Kyōkai (Association of Japanese Educational Kamishibai) in 1938 by Matsunaga Ken’ya (1907–96).

Since many members of the Association of Japanese Educational Kamishibai were elementary school teachers, its initial activities were primarily creating, studying, and illustrating fairy tales and lending kamishibai. Some teachers expanded their operation beyond schools and performed paper plays to the public as part of the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement (1938), whether on the street or at department stores, amusement parks, or beaches. In the same year, the association produced the first national policy (kokusaku) kamishibai, aiming to mobilize every Japanese citizen. While performers of paper plays were primarily teachers, they also included Christian ministers, Buddhist priests, town hall officials who disseminated home front ideology, and post office staff who promoted savings and sold war bonds.

Regional governments soon found that kamishibai was a handy art that had little spatial, technical, or temporal limitations. Local officials even produced and performed kamishibai featuring local stories to indoctrinate and entertain residents.

Unlike street kamishibai, national policy kamishibai were single stories rather than an episode of a serial narrative. This led producers to increase the number of cards to twenty per play, give or take. Also, narratives generally fell into one of three categories—informational, exhortation, and emulation. Informational-style plays provided factual information about real events or instructions on how to do things using realistic imagery, such as diagrams for building a bomb shelter in one play and for securing your door in another (Kokoro no kagi, 1943).

The exhortation-style encouraged audiences to do something, such as buy war bonds, participate in the neighborhood association (Tonarigumi, 1941), or recycle goods for the war effort (Tetsu no kobito, 1941). The emulation-style kamishibai inspired viewers to emulate the heroic deeds of others but in a less direct way than the narratives of the other types. Instead the audience was meant to connect personally with the narrative and be moved by the self-sacrifice or discipline of the main characters, such as in Mother of a War God (Gunshin no haha, 1942).

After regulations on kamishibai professionals were issued in 1938, paper plays were censored before their publication and performers were required to strictly follow the instructions written on the sheets. Tokei wa ikiteiru (A clock is alive), produced in 1941, exemplifies this with idealized Japanese soldiers instead of the realities of war. National policy kamishibai were often sanitized to show Japanese soldiers in pristine uniforms and without reference to enemies in the battlefield. Also, the ideology of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity pops up regardless of the script.

Illustrators

In addition to scriptwriters, performers, and audiences, illustrators were essential to the kamishibai propaganda campaign. Often aspiring fine art painters, the illustrators had to draw tens of kamishibai sheets a day to make a living. To encourage their artistic side, the Association of Japanese Educational Kamishibai hired fine art painters such as Fukuda Toyoshirō (1904–70) and Miyamoto Saburō (1905–74) as reviewers of kamishibai illustrations as early as November 1941. The association’s most senior illustrator, Nishi Masayoshi, was ambivalent about kamishibai’s artistic value and capacities compared with those of the fine arts. He asserted that Japan’s victory was more essential than art, saying, “No fine arts would be valued if Japan is defeated.”

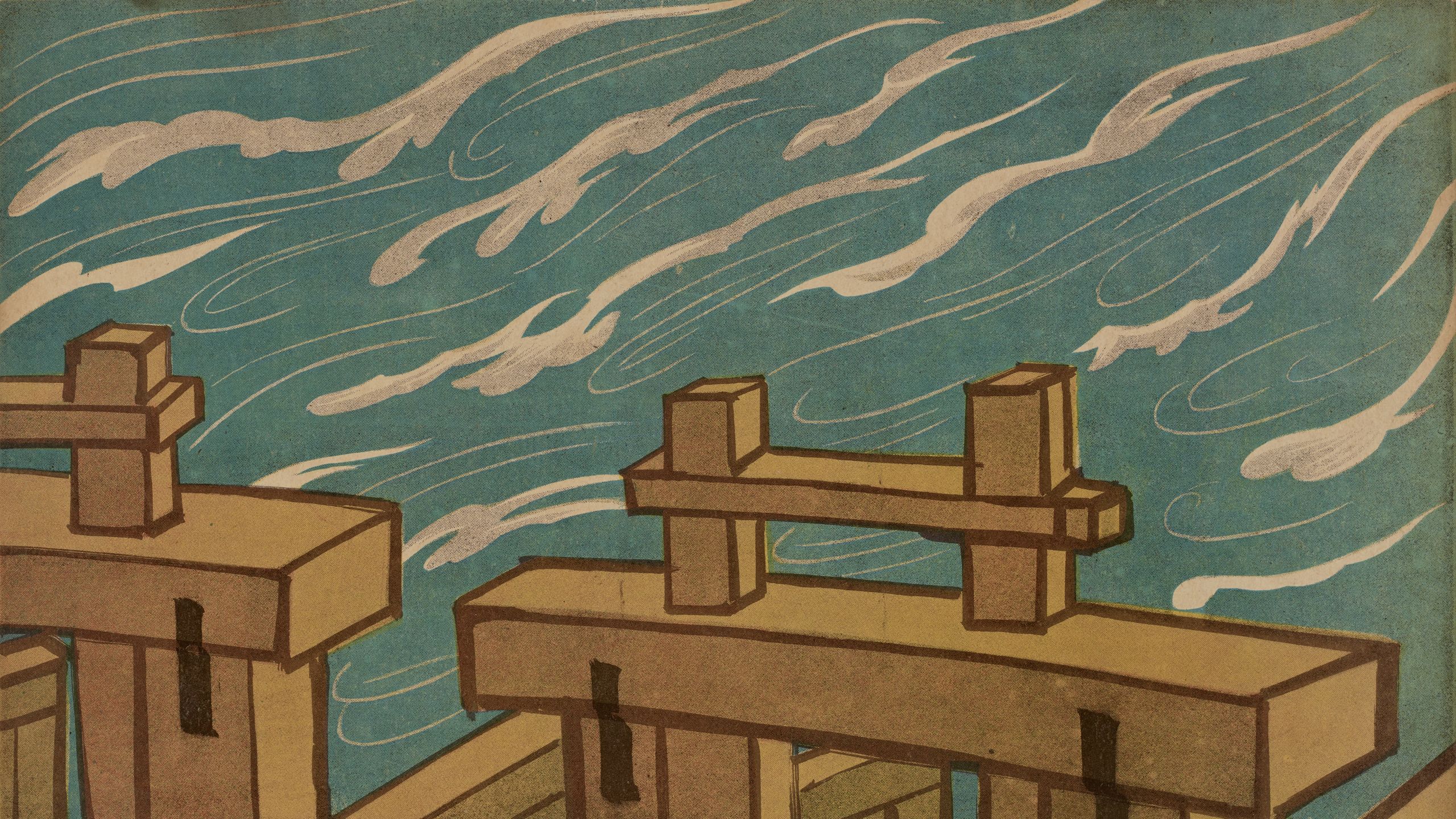

An example of artwork by Fukuda Toyoshirō (at left: Attack on British Borneo, ca. 1942) and kamishibai illustrations by Nishi Masayoshi (at right: The Case of the Bound Jizo, 1941). Courtesy of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and Cotsen Children's Library Collection.

An example of artwork by Fukuda Toyoshirō (at left: Attack on British Borneo, ca. 1942) and kamishibai illustrations by Nishi Masayoshi (at right: The Case of the Bound Jizo, 1941). Courtesy of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and Cotsen Children's Library Collection.

Overall, kamishibai creators, illustrators, and performers focused on their roles as educators and messengers of whatever the prevailing political and military current was. They did not ask questions and remained a part of the receiving end of policy directives. In this way, they were no different from the popular masses. They failed to become intellectual leaders or real artists who looked to the longevity of their work beyond the war.

The Imperial Rule Assistance Association

More Japanese were mobilized to participate in the local kamishibai movement after the Imperial Rule Assistance Association was established in 1940. The association incorporated community organizations and tonarigumi (neighborhood associations) into the organization. The propaganda aspect, accessibility, and indoctrinating qualities of kamishibai were significant to them, and they performed kamishibai in their regular meetings. The paper play movement spread from urban areas to rural communities in 1941. For example, a post office clerk in the rural area of Kashiwazaki city, Niigata Prefecture, narrated paper plays at concert halls and temples, attracting as many as 140 to 200 spectators for each twice-daily show. Over time the association increasingly valued kamishibai and mandated that at least one performer, or someone knowledgeable about kamishibai, be present at every regular meeting. As a result, the number of participants in paper play training sessions quickly grew.

In addition to the youth groups and women’s associations, two organizations actively performed kamishibai: Yokusan Sōnendan (Imperial Rule Assistance Young Men’s Corps) and Sangyō Hōkokukai (Industrial Patriotic Association). The Young Men’s Corps was established as a frontline unit of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association and became active kamishibai performers, particularly in rural and farming communities. Most likely perceiving themselves as local elites, the corps members culturally tried to distinguish themselves from the yokels.

Sugō Naonori, a leading kamishibai narrator in Gōda village, Hiroshima Prefecture, preached to corps members about how kamishibai should be performed. He explained, “Performers should maintain an inculcating quality. Only leaders should qualify. Kamishibai should not be degraded to a country play, hobby, or entertainment of country cousins. To this end, the members should maintain contact with one another to improve performance skills and artistic quality constantly.”

The Imperial Rule Assistance Association focused on provincial culture as an engine to disseminate its sphere of cultural influence, such as in their paper play Dawning Village (Akeyuku Mura, 1942).

The kamishibai production by the Society of Aizu Culture exemplifies the association’s mission in provincial cities. The society made kamishibai featuring benevolent mothers as a pillar of the home front and, through 150 performances, mobilized more than thirty thousand audience members from October 1941 to 1943.

Card 8 from Mother of a War God, June 10, 1942. Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.10) With his mother’s hard work and support, Sadamu became a celebrated war god after his attack on Pearl Harbor in defense of the country.

Card 8 from Mother of a War God, June 10, 1942. Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.10) With his mother’s hard work and support, Sadamu became a celebrated war god after his attack on Pearl Harbor in defense of the country.

Founded in 1940, the Industrial Patriotic Association mobilized a myriad of the factory, mine, and office workers for home front efforts. The Association of Japanese Educational Kamishibai enthusiastically dispatched lecturers to them. Kamishibai shows began popping up at factories, mines, and offices in 1941. After organizing workplaces into smaller units, the equivalent of a neighborhood unit of five households, the Industrial Patriotic Association encouraged unit leaders to host regular meetings to foster leadership at a micro level.

As part of the mobilization of production labor forces, the Industrial Patriotic Association formed three teams in October 1941: theater, motion pictures, and kamishibai. The motion pictures team was by far the most successful, hosting shows at 728 locations nationwide, compared with theater performances at 535 and paper plays at only 178. In Tochigi Prefecture, the association hosted traveling movie theaters at ninety-five locales, attracting audiences of about 72,000 people, compared with kamishibai at forty-three locations with 3,320 spectators.

Card 13 from Rabaul and the Nail Clippers, August 15, 1944. Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.17). Sadao: "I hear that they sent us back to Japan to be of service to the plane and ship production. I understand that we are to report vivid details of the battles to encourage the industrial warriors to work harder. I decided to visit factories starting tomorrow."

Card 13 from Rabaul and the Nail Clippers, August 15, 1944. Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.17). Sadao: "I hear that they sent us back to Japan to be of service to the plane and ship production. I understand that we are to report vivid details of the battles to encourage the industrial warriors to work harder. I decided to visit factories starting tomorrow."

From 1942, the Great Japan Association of Patriotic Industry shifted its focus from dispatching kamishibai performers from its headquarters to encouraging local units to narrate paper plays. This change indicates a new strategy for promoting kamishibai, which faced an uphill battle with its strong rival, motion pictures. The feedback on the “touring performances to comfort workers and discourage industrial worries” received from factories in Osaka in April 1942 shows that the types of entertainment in demand were manzai (stand-up comedy), rōkyoku (narrative singing), music, and movies. A coal miner commented, “We don’t have any breathing room if we have to hear about work during break. We will enjoy entertaining pieces like Torazō zukushi. We will never rest if we have to watch a kamishibai based on our work at meetings in the evening.” Ōgushi argues that the association promoted individual worker initiatives in cultural practice and positioned kamishibai as “wholesome entertainment” as a countermeasure against reckless creativity and juvenile workers’ immoral conduct. Ōgushi suggests that the kamishibai movement was most active among laborers in mining and forestry.

Grassroots

Grassroots participation in kamishibai productions expanded beyond the Association of Japanese Educational Kamishibai. Small-scale organizations and individual producers emerged, creating and performing their own paper plays. Although scattered documents on this topic make it difficult to grasp the entire picture, Ōgushi identifies three venues: contests, regional performances, and gatherings with performances by nonaffiliated individuals.

A wide variety of organizations called for home front kamishibai scripts to enter competitions, including the Association of Taiwan Kamishibai in that Japanese colony. Although the applicants were strikingly diversified, most of them were teachers displaying an effort to create and perform paper plays with children. Small groups of individuals, whether they belonged to local governments or branches of the Association of Japanese Educational Kamishibai, created and performed their own handmade kamishibai.

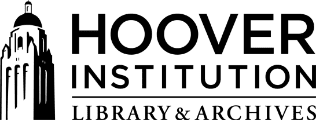

A lecture using kamishibai, likely on Japanese health and hygiene during the occupation period. Crawford F. Sams Papers, Hoover Institution Archives (79066.002)

A lecture using kamishibai, likely on Japanese health and hygiene during the occupation period. Crawford F. Sams Papers, Hoover Institution Archives (79066.002)

Some Japanese individuals without an organizational affiliation made private kamishibai. A farmer named Shiraishi Hiromoto in Furutsuki village, Fukuoka Prefecture, made a four-volume paper play titled Food Production Increase. Shiraishi worked during the day and in the evening met with neighboring farmers to promote food production through kamishibai. Endō Shōji was another individual who voluntarily helped home front food production by creating kamishibai. Endō eventually took a position at a local town hall, spurring the spread of paper plays in the area. The topics covered were neighborhood meetings; savings promotions; rice, food, and coal production increases; and quota deliveries of rice to the government. He argued for the benefits of kamishibai created by the performer. To him, national policies were best implemented through person-to-person interactions and by evoking empathy. Kamishibai best fit the task.

National Policy Kamishibai Performed

Two kamishibai from the Hoover Institution Archives have been brought to life through the collaboration of Hoover staff (in California) and professional actor Ichirō Kataoka (in Japan) during the pandemic in 2020. While the original kamishibai cards and narrator remained physically apart, the resulting videos provide the unique opportunity to experience national policy kamishibai as more than just script and illustrations but as intended: performance art.

Oka Midori (artist), Hirano Tadashi (author), Zenkōsha Kamishibai Kankōkai (publisher). My Beloved Horse Joins the Army, June 1, 1941. Kamishibai with 16 lithographs. Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.09)

This material includes passages originally published in Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan (2021) by contributors Kaoru (Kay) Ueda, Taketoshi Yamamoto, and Tsuneo Yasuda. We are most thankful for their permission to use the materials online.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team. For more information about rights and permissions please visit:https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.