Kamishibai Defined

A Core Topic of Modern Japan

Kamishibai, literally “paper theater” in Japanese, is a form of storytelling that combines a set of standard-size illustrated paper cards paired with a scripted performance by a narrator. A form of performance art, the cards (illustrated on the front with script on the back) would be cycled through a transportable wooden stage (butai) by the kamishibai narrator as they dramatically brought the imagery to life.

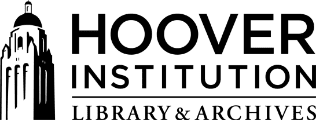

Two kamishibai cards from Five Estate Owners (ca. 1940), which show the illustration on the front of card 10 and its accompanying script printed on the back of card 9.

Two kamishibai cards from Five Estate Owners (ca. 1940), which show the illustration on the front of card 10 and its accompanying script printed on the back of card 9.

An audience would gather once they heard a performer clap together their hyōshigi (two wooden blocks), or ring of a metal bell, sounding the beginning of the show. Often referred to as Kamishibai no Ojisan, literally “Uncle Kamishibai,” the best narrators would incorporate hand gestures and various sound effects into their performances. Those who performed Street Kamishibai, would often carry their stages affixed to a bicycle and travel around town performing to groups of children several times a day. Their financial incentive came not from charging for the performance, but rather charging children for candy—which came with a kamishibai performance. This model was born out of a time of economic depression in Japan and became the most commonly reminisced about version of kamishibai.

An op-ed published in the Asahi shinbun on September 19, 1933, likened kamishibai to opium for children. It went on to express that children, as naturally eager story-listeners, were the ideal audience as kamishibai provides just that. The kamishibai created a unified space where the performer and the audience "breathe the same air seamlessly." This highlights the reality of early kamishibai: that it was child consumer-centric. While the most accessible and inexpensive daily entertainment for young masses, kamishibai became popular largely because they were not ideological, but practical. They did not preach to the children, as teachers or religious leaders might. Instead their goal was entertainment.

Imai Yone performing kamishibai, ca. 1933.

Imai Yone performing kamishibai, ca. 1933.

Imai Yone (1897–1968) estimated that in 1933 Tokyo there were 2,500 kamishibai performers. They would perform on average ten times a day to audiences of roughly 30 children. Her estimate for the gross audience number was 75,000 children daily—indicating that some watched more than one a day. By 1937, it is estimated that there were nearly 30,000 performers across Japan, performing to a minimum of one million children daily. Kamishibai had developed into various forms by this time, most notably street and educational kamishibai, but first an examination of how kamishibai emerged.

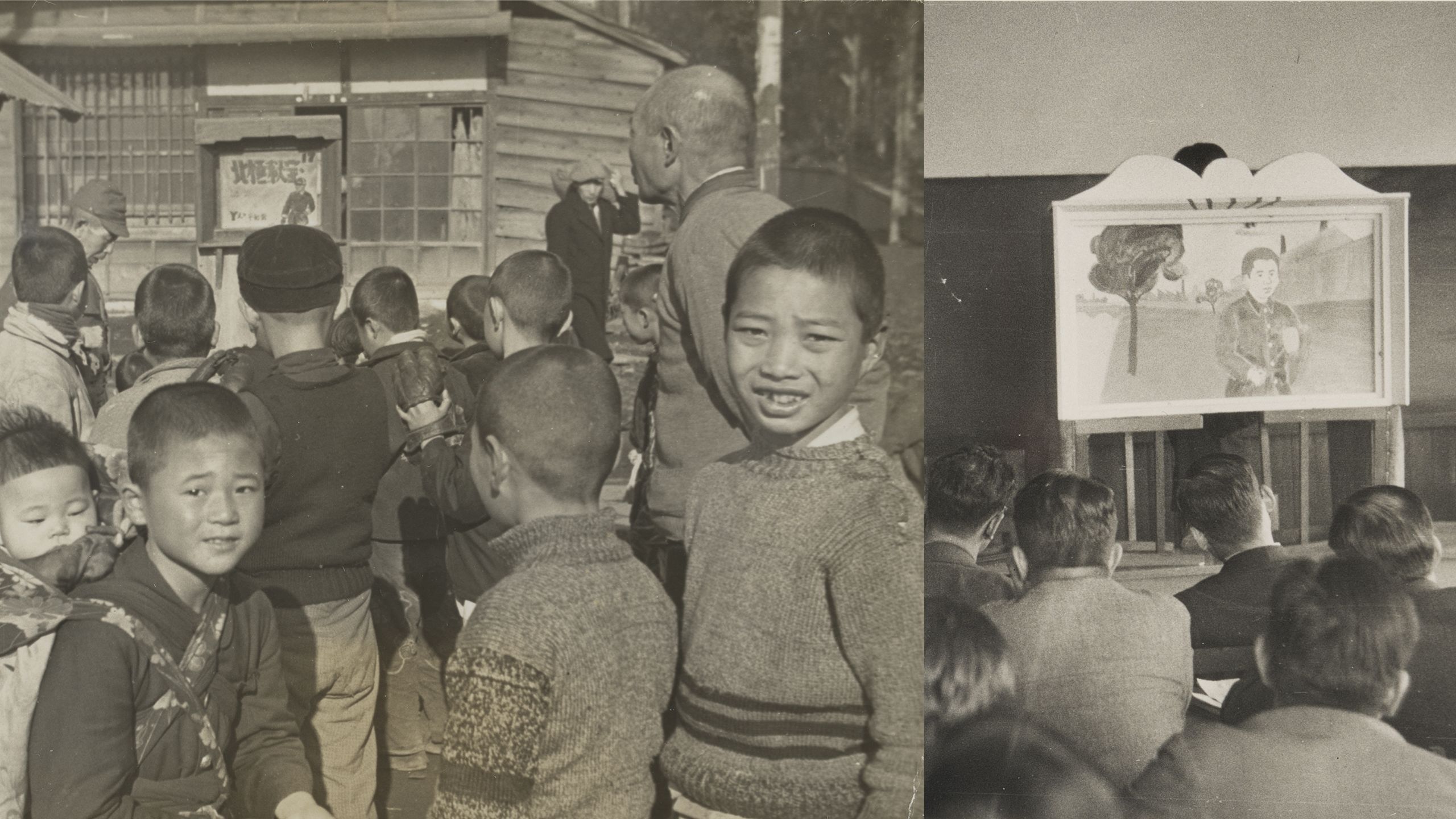

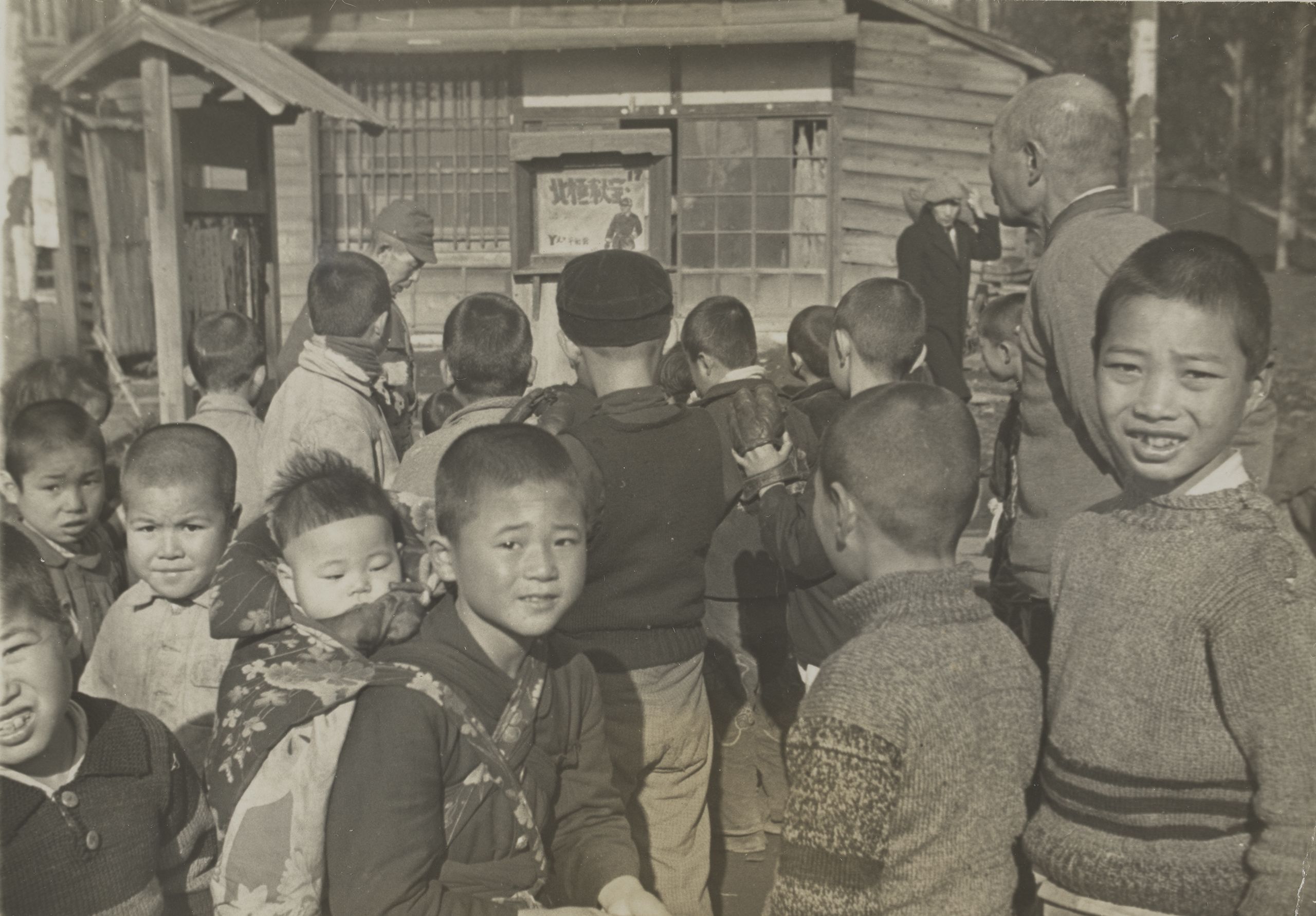

Background images: at left is Kamishibai performance, titled “Hokkyokuhiho” (A Secret Treasure of the North Pole), December 1946; at right is A lecture using kamishibai, likely on Japanese health and hygiene, ca. 1946. Crawford F. Sams Papers, Hoover Institution Archives (79066)

Enemy Surrender (敵国降伏 Tekikoku kōfuku), August 31, 1944. Torii Kiyonobu (artist), Adachi Naorō (author), Suzuki Keizan (editor), Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Kyōkai (producer). Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.03)

Enemy Surrender (敵国降伏 Tekikoku kōfuku), August 31, 1944. Torii Kiyonobu (artist), Adachi Naorō (author), Suzuki Keizan (editor), Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Kyōkai (producer). Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.03)

| The Evolution of Kamishibai

The art history of Japan has no linear line leading to the birth of kamishibai. However, earlier practices and traditions certainly influenced its evolution.

E-toki

Translating roughly to “picture storytelling,” etoki is a Japanese tradition dating back to the 11th century. Early examples include Buddhist monks explaining a story or scripture as they pointed to emaki (painted hand scrolls) or the walls in painted picture halls.

A festival at the Sumiyoshi Shrine [detail from bottom right depicting Kumano bikuni performing etoki at the foot of the bridge to the shrine], early 17th century, from a pair of sixfold screens. Freer Gallery of Art (F1900.25)

A festival at the Sumiyoshi Shrine [detail from bottom right depicting Kumano bikuni performing etoki at the foot of the bridge to the shrine], early 17th century, from a pair of sixfold screens. Freer Gallery of Art (F1900.25)

Utsushi-e

Developed from magic lantern slides introduced in the 18th century from Holland, utsushi-e merged the tradition of storytelling with images and accompanying music. First popularized by Miyakoya (Kameya) Toraku in 1803, colorful paintings on glass slides would be rear projected onto rice paper screens as orators performed stories to music. Performances often involved multiple skilled performers able to quickly move the slides through flame lit lanterns. The tradition would eventually merge with updated European techniques in the Meiji era and become known as gento, which were widespread by the end of the 19th century—performed regularly at theaters, schools, temples and even some homes. Performances based on the First Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars became particularly popular.

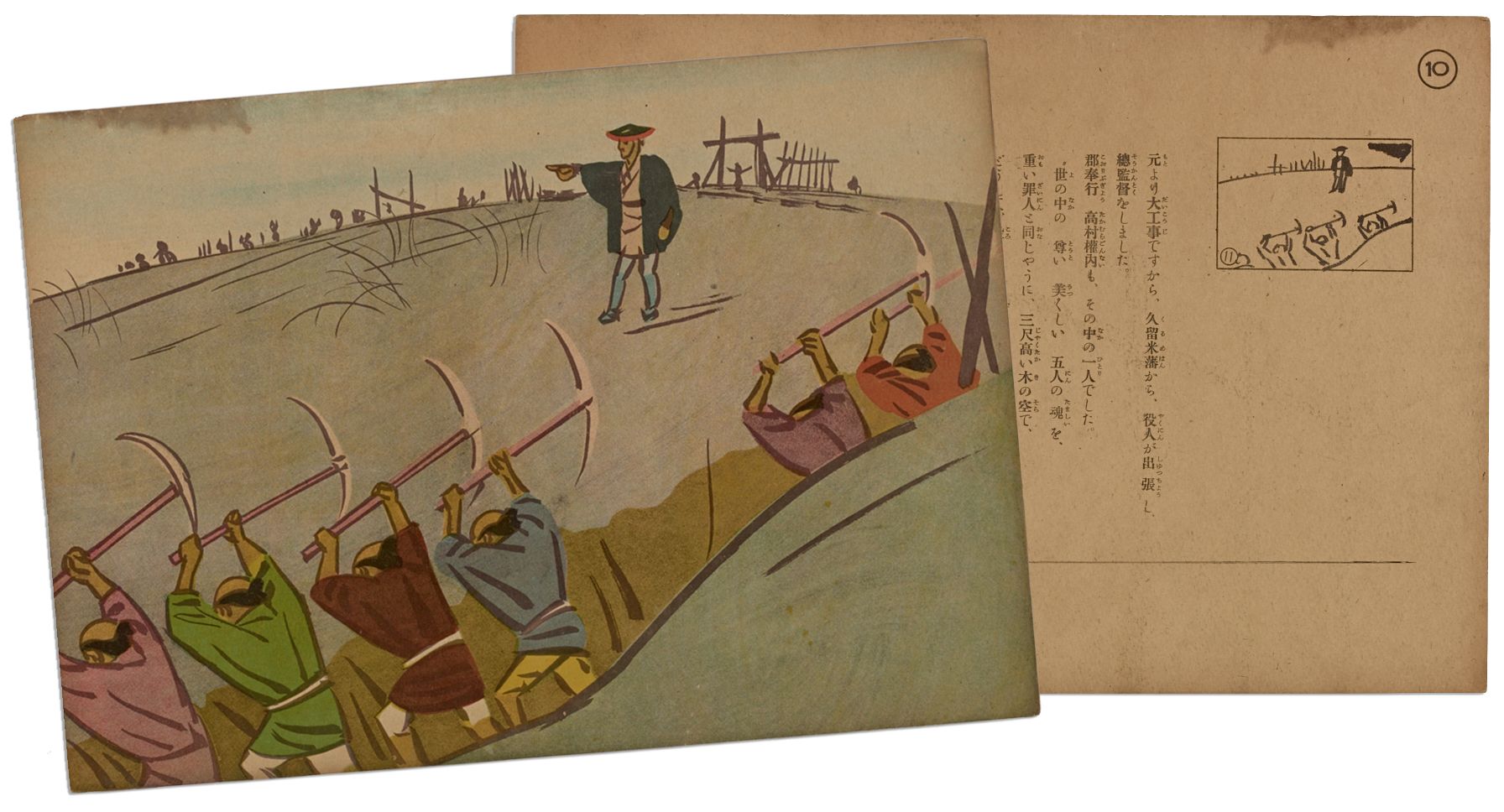

Sketch of a small scale utsushi-e performance. Courtesy of Waseda University's Utsushi-e website

Sketch of a small scale utsushi-e performance. Courtesy of Waseda University's Utsushi-e website

Tachi-e

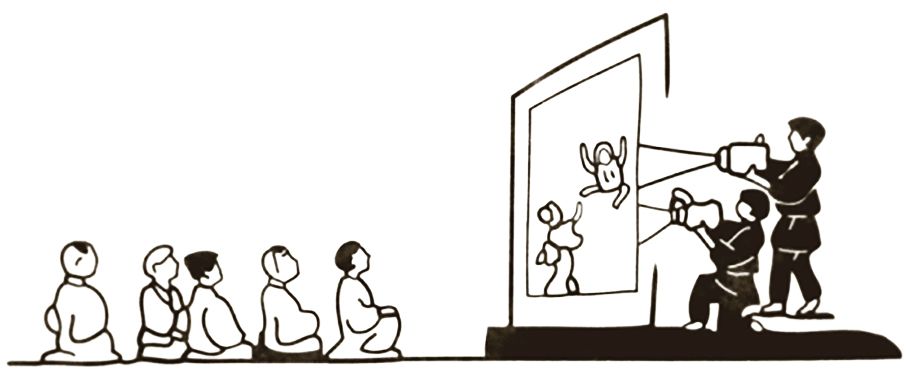

Literally “stand-up pictures,” tachi-e is believed to have been started by woodblock print artist Shin-san (Hagiwara Shinzaburō), the disciple of a celebrated Japanese rakugo comedian, San’yūtei Enchō. Tachi-e is considered the immediate precursor to modern kamishibai, with Shin-san’s hand-illustrated cutout puppets first used as a curtain-raiser in 1897. A tachi-e puppet is two sided and affixed to a stick, allowing performers to quickly flip the image and create a sense of motion, with the backgrounds painted black to blend in with the black curtain inside a portable wooden stage. Making this kind of performance much more transportable than utsushi-e.

Left puppet: Zen-san, Ōmaeda Eigorōca, 1900. Center puppet: Take-san, Priest Miyoshi Seikaica, 1907. Right: Three puppets from The Parable of the Good Samaritan (top row are front sides with back sides below them and a third at the bottom). All illustrations from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

Left puppet: Zen-san, Ōmaeda Eigorōca, 1900. Center puppet: Take-san, Priest Miyoshi Seikaica, 1907. Right: Three puppets from The Parable of the Good Samaritan (top row are front sides with back sides below them and a third at the bottom). All illustrations from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

The use of paper puppets in tachi-e led audiences to view this form of entertainment as cheaper than that of utsushi-e, with some derogatorily calling it “paper theater” or kamishibai. The dramatic tales performed with tachi-e puppets became so popular that a network of kashimoto (rental) companies emerged and further spread attendance opportunities. However, these street performances often sensationalized their content and were subject to frequent bans by the government.

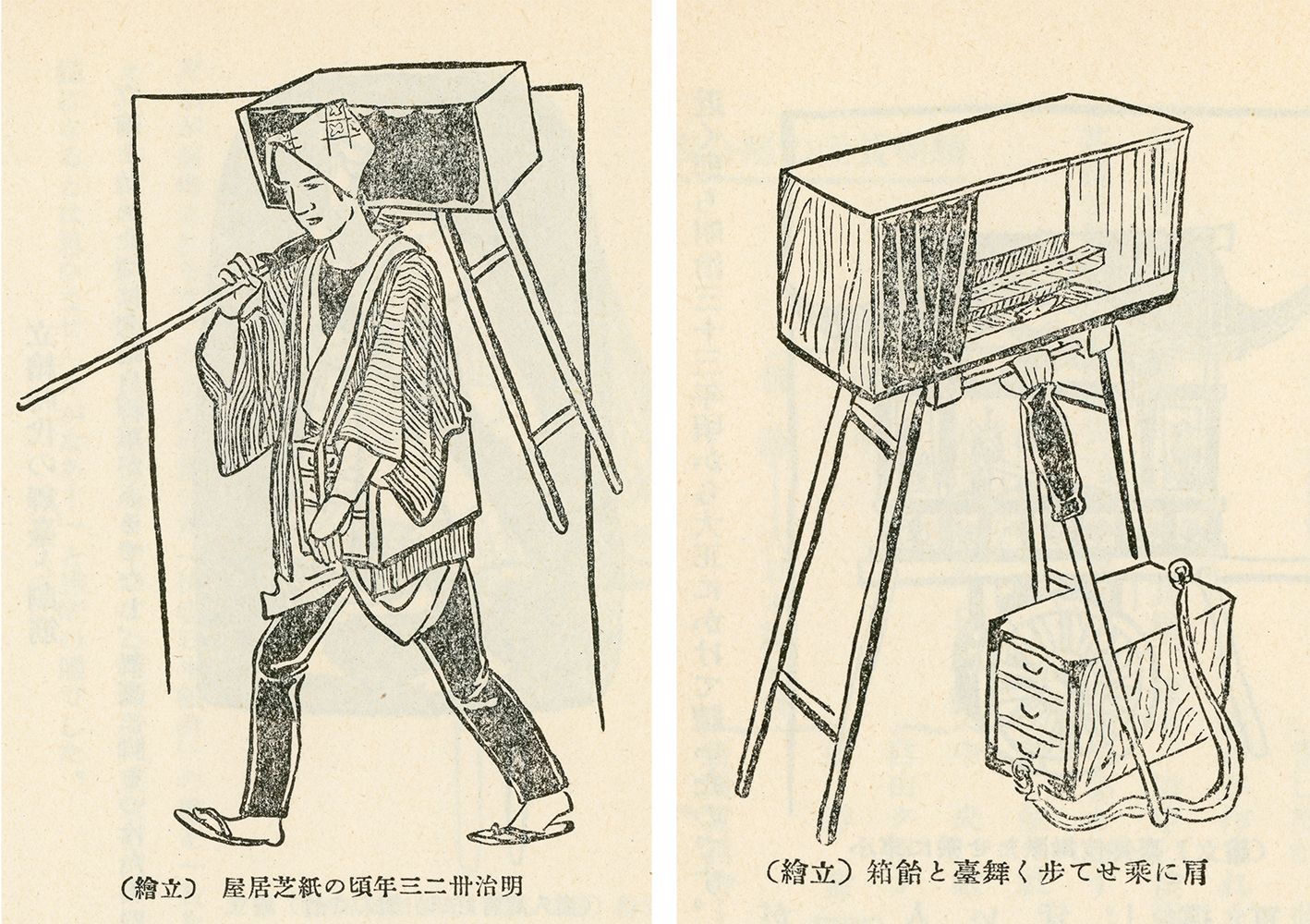

Left: Kamishibai-ya (performer), circa 1900. Right: The transportable tachi-e stage with accompany candy box. All illustrations from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

Left: Kamishibai-ya (performer), circa 1900. Right: The transportable tachi-e stage with accompany candy box. All illustrations from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

At about the same time, the Zen monk Nishimura developed the Japanese tradition of illustrated narration into a form similar to today’s kamishibai, by preaching Buddhism to children. Puppeteers out of work bought picture books from bookstores and created kamishibai using Nishimura’s method.

Hira-e

Literally “flat pictures,” hira-e is what we recognize as kamishibai today. In order to skirt a ban on tachi-e, performers adjusted their methods and created flat illustrated cards to pull through their transportable theaters. They then combined this with the dramatic staging seen in silent films that were in vogue at the time. The first performances appeared in 1930 and while performers named their “new picture-stories” shin e-banashi, audiences were soon calling them kamishibai.

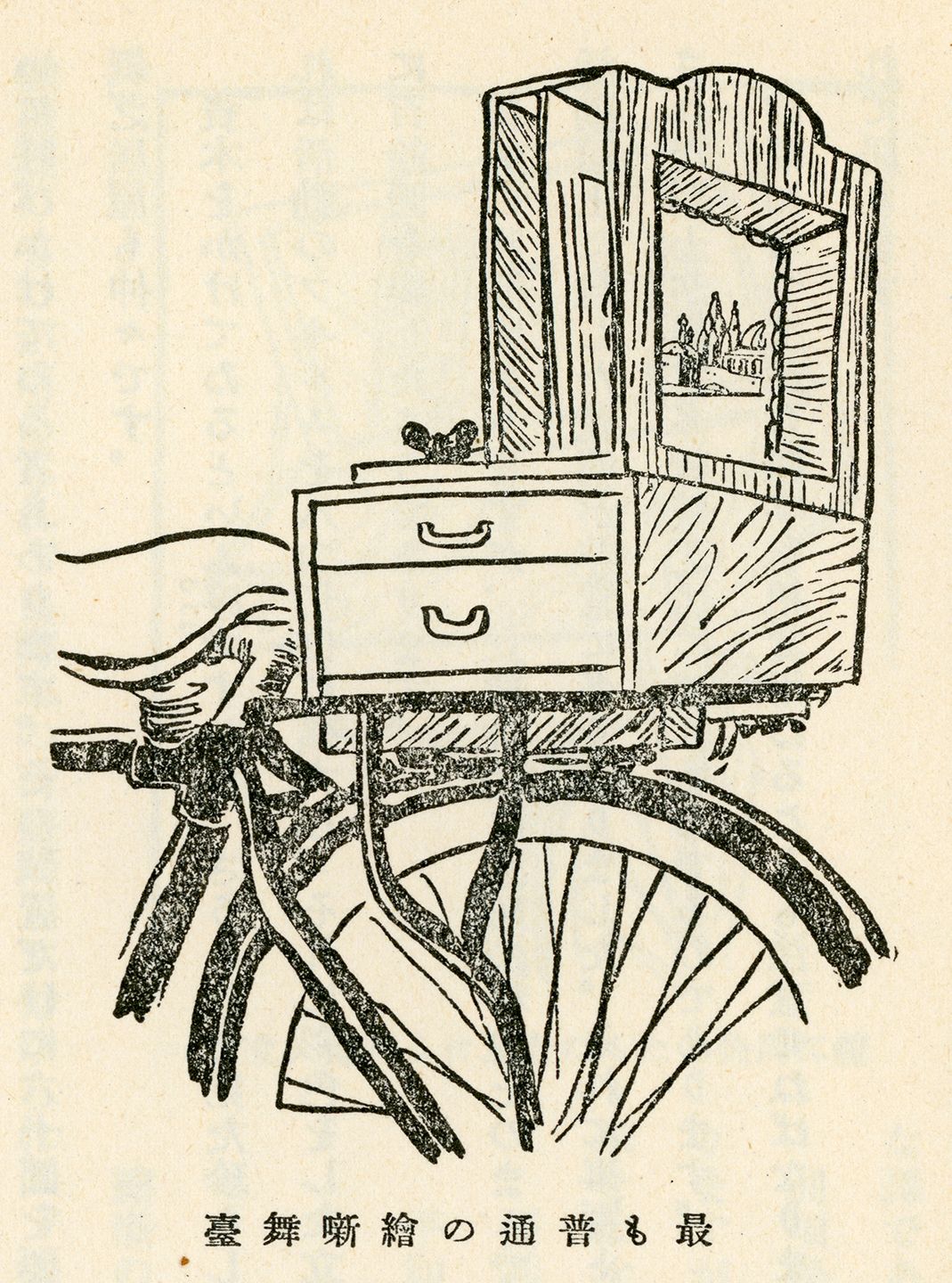

A typical e-banashi (picture-story) stage. Illustration from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

A typical e-banashi (picture-story) stage. Illustration from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

| Types of Kamishibai

Street (Gaitō) Kamishibai

Street (gaitō) kamishibai emerged from the second half of the 1920s to the early 1930s. A performer carrying a rotating station of paper plays on a bicycle gathered children on the street and in the fields. Young audiences, with mouths full of candy that they had bought from the performer, watched sheet after sheet of colorful cartoons as the performer narrated a story. During the Shōwa depression, which was triggered by the Great Depression in the United States, many jobless men turned to performing kamishibai for immediate income. After the emergence of the megahit adventure play Golden Bat, a quintessential portrayal of poetic justice, with virtue conquering evil, came the golden age of street kamishibai.¹

Golden Bat kamishibai

Golden Bat kamishibai

A typical performance would revolve around three short narratives, something humorous and cartoonish for the youngest children, a melodrama for the older girls and an adventure tale for the older boys. The latter two would often be a single episode of a larger serial narrative that might last months, leaving children eager for the next day’s performance. In prewar street kamishibai, each episode would have 10 to 15 cards that were typically hand painted on one side with handwritten scripts or notes on the back. Most performers would be told the plot at the kashimoto (lenders) they rented the plays from and bring their own interpretation to the story. Once kamishibai producers switched to lithography the scripts were formally printed on the back, but performers still embellished in their own styles.

The hard economic times inevitably hit Japanese homes. Many parents reduced their children’s allowances to a level that was not enough to go to movies but sufficient for kamishibai viewings. The survey conducted on 1,170 boys and 500 girls in Tokyo in the summer of 1936 reveals that 313 boys and 34 girls saw kamishibai twice a day; 138 boys and 53 girls, three times a day. Five boys and one girl responded staggeringly that they attended six times a day. The depression of the 1930s had a well-known consequence—the rise of fascism in Japan. Ironically, it also had a side product— it spurred the growth of the kamishibai market.

After war in China escalated in the late 1930s, the number of men pulled into the military or labor force depleted the number of street kamishibai performers. Almost as soon as Japan surrendered in 1945, however, newly out of work men once again turned to street kamishibai for income. Some kashimoto even offered the enticement of housing, food, and clothing for their performers—needed by many in a devastated Japan beginning to rebuild.

Background image: Kamishibai performance, titled “Hokkyokuhiho” (A Secret Treasure of the North Pole), December 1946. Crawford F. Sams Papers, Hoover Institution Archives (79066)

Educational (Kyōiku) Kamishibai

After the 1931 Manchurian Incident (Mukden Incident), the Japanese imperial government became more involved in the dissemination of kamishibai. In September 1932, the Ministries of Home Affairs, Army, and Education sponsored the establishment of Nihon Kyōiku Gageki Kyōkai (Association of Japanese Educational Pictorial Plays) with twenty-five hundred member businesses. Vice Minister of Education Andō Masazumi was appointed chairman. In the same month, the Ministry of Army sponsored an evening of kamishibai performances commemorating the Mukden Incident’s first anniversary at Sumida Park in Asakusa to render service to military education.³

Gospel (Fukuin) Kamishibai

The format change from tachi-e, which used cutout puppets on sticks, to kamishibai, which used full-page paper illustrations, revolutionized street theater. Printing kamishibai brought yet another breakthrough. Imai Yone (1897–1968) was arguably the Johannes Gutenberg of Japanese educational kamishibai. A graduate of Tōkyō Joshi Kōtō Shihan Gakkō (Tokyo Women’s Normal School, which is today’s Ochanomizu University), she also majored in theology at the University of California for four years in 1928–32. After returning to Japan, she single-handedly started a missionary and Sunday school at Hayashi-cho, Honjo-ku. Forty to fifty children gathered there daily.

One Sunday, the regulars did not appear at Sunday school, except for five or six children. Even those that came acted impatiently and asked, “Miss Imai, kamishibai is coming. I’d love to see it. Can I go?” “After kamishibai is over, I’ll come back.” I lost all my children to kamishibai.⁶

Viewing kamishibai with children persuaded Imai to make a version based on the Bible. Although the initial reaction from church officials was muted, they gradually warmed up to the idea of a collaborative production of gospel kamishibai. The kamishibai mission was established in August 1933, marking the birth of the mass production of kamishibai by lithographic printing as a form of mass media.

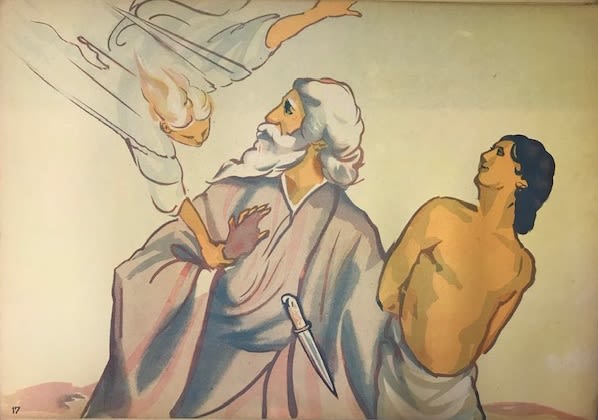

Card 17 from Biblical Tales: Abraham (聖書物語: アブラハム), published by Kamishibai Kankōkai, 1934. Courtesy of Cotsen Children's Library (11586463)

Card 17 from Biblical Tales: Abraham (聖書物語: アブラハム), published by Kamishibai Kankōkai, 1934. Courtesy of Cotsen Children's Library (11586463)

Kamishibai Kankōkai (Kamishibai Publisher) was the publishing arm of the Tokyo Young Men’s Christian Association and published the first printed gospel kamishibai in January 1935. Imai Yone edited and Hirasawa Teiji illustrated Kurisumasu monogatari (Christmas story) and Iesu den (The life of Jesus).

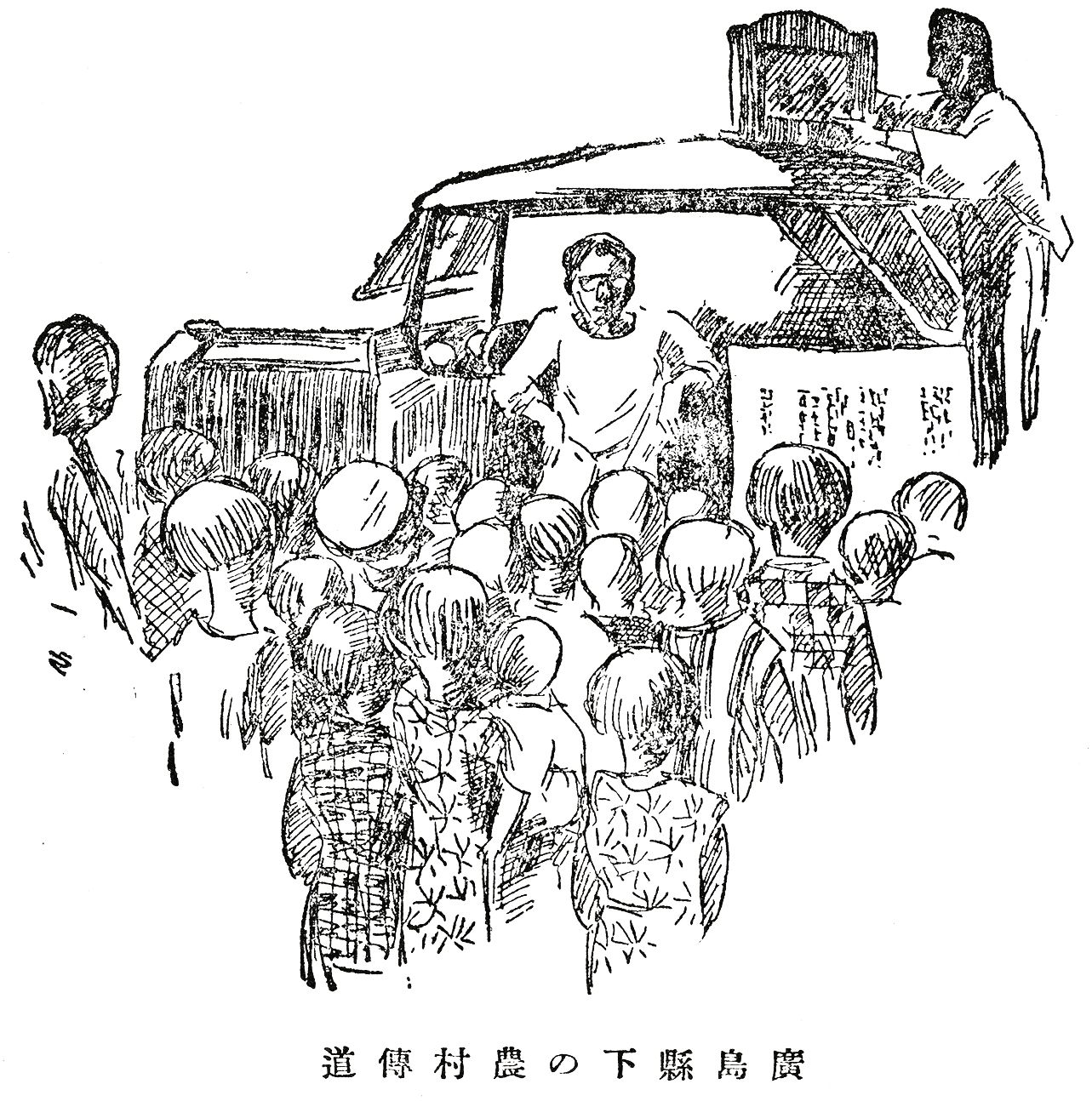

Gospel kamishibai and its use. Illustration from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

Gospel kamishibai and its use. Illustration from “Kamishibai no jissai” by Imai Yone (1934).

Buddhist Kamishibai

Christian-printed kamishibai kindled Buddhist interest in kamishibai as a proselytization tool. In 1935, Takahashi Gozan (1888–1965) established Zenkōsha, a publisher of kindergarten kamishibai. A former picture book writer, Takahashi also performed his kindergarten kamishibai, modeled after Disney picture books and Buddhism paper plays. In March of the following year, Uchiyama Kenshō (1899–1979) published a sixteen-sheet four-color kamishibai via offset printing, titled Hanamatsuri (Buddha’s birthday). Other Buddhist schools quickly followed suit: Shinran shōnin den (The life of Shinran) by Ōtani-ha of the Hongan-ji temple in fall 1936, and Sōso den (The life of the founder) by the Sōtō school in spring. Zenkōsha published the so-called kindergarten kamishibai Akazukin (Little Red Riding Hood) and Hanasaka jī (The old man who made the trees blossom) to discourage kindergartners from attending street kamishibai performances. This type of kamishibai distinguished itself because it was printed or mimeographed for preaching and enlightenment and was purchased by adults.

Matsunaga Ken’ya

Imai’s method of presenting kamishibai to educate audiences also inspired educator Matsunaga Ken’ya (1907–96). While a student studying education at the Imperial University of Tokyo, Matsunaga had participated in helping the victims of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. There he noticed the effectiveness of kamishibai. This led Matsunaga to adapt the Soviet movie Road to Life into the 1933 kamishibai Jinsei annai about transforming street children at a labor commune rather than a correctional facility. Later, while teaching at an elementary school in Tokyo, Matsunaga started a campaign distributing mimeographed kamishibai throughout the country and founded the Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Renmei (Federation of Japanese Educational Kamishibai) at his residence in 1937. The federation primarily consisted of teachers and those involved in the teaching of tsuzurikata (writing) and had nationwide success.

On July 20, 1938, Matsunaga reformed the organization as Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Kyōkai (Association of Japanese Educational Kamishibai). It was the most significant engine for promoting educational kamishibai, and it penetrated the school system with printed paper plays. With support from Ōshima Chōzaburō (1904–83), a former director of Teikoku Shōnendan Kyōkai (Imperial Youth Group Association), who wrote under the pen name Aoe Shunjirō, it was established to promote national policies and uplift wartime morale. The founding members included tsuzurikata teacher Kokubun Ichitarō, children’s literature scholar Horio Seishi (1914–91), and religious scholar Saki Akio. Matsunaga then crowned it with Ōshima Masanori (1880–1947).

Card 17 from Children in a Grass Field (原っぱの子供達), November 25, 1941. Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Kyōkai (publisher). Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.07)

Card 17 from Children in a Grass Field (原っぱの子供達), November 25, 1941. Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Kyōkai (publisher). Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.07)

The educational kamishibai promoters were critical of the noneducational character of street paper theater. They contended that its vulgarity, impropriety, distasteful colors, sickly and exaggerated figures, and infestation of absurd monsters, paired with its corrupting influence on innocent children through the portrayals of romance, ferocious acts like bullying and even murders, and the foul instructions of the performers, combined to have an “intense impact on children.”⁷ Ironically, educational kamishibai creators learned best practices from street kamishibai. Without kamishibai’s existing popularity among children, print kamishibai may not have penetrated the spheres of education and fascism.

Background image: Card 20 from Enemy Surrender (敵国降伏 Tekikoku kōfuku), August 31, 1944. Torii Kiyonobu (artist), Adachi Naorō (author), Suzuki Keizan (editor), Nihon Kyōiku Kamishibai Kyōkai (producer). Kamishibai Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2018C32.03)

This introductory material includes passages originally published in Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan (2021) by contributors Kaoru (Kay) Ueda, Taketoshi Yamamoto, and Tsuneo Yasuda. We are most thankful for their permission to use the materials online.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team. For more information about rights and permissions please visit:https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.