Nishiki-e Defined

A Core Topic of Modern Japan

Nishiki-e is an Edo specialty unrivaled by the other regions. Those prints that are gorgeously colored find fans of high status. They are admired throughout Japan.

—Edo meisho zue (1834)

Nishiki-e is one form of ukiyo-e. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, depicting lively contemporary scenes and individuals, were born in the second half of the seventeenth century, based on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century genre paintings. Large supplies of ukiyo-e at low prices, made possible after Hishikawa Moronobu (?–1694) incorporated woodblock printing into their production, spurred wide distribution throughout every social stratum.

Ukiyo-e woodblock prints were initially printed singularly in black ink, but later were cursorily painted in a few colors by brush. By the 1740s, a simple printing technique using two to three colors was developed. Ukiyo-e was further developed into nishiki-e, fully colored from corner to corner. Suzuki Harunobu (?–1770), with a keen sense of color, took the lead in this development. Nishiki, literally meaning “brocade” in Japanese, was synonymously used to depict beautiful colors comparable to contemporary brocades. Intricate embossing and delicate gradation further evolved the nishiki-e printing technique into high-level woodblock multicolor printing toward the end of the Edo period (1603–1868).

Background Image (detail of): Utagawa Yoshimori (1830–1884). Miyozaki Yokohama at a Glance, 1860. Ōban diptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.045)

Suzuki Harunobu (?–1770). [Poetess Ono no Komachi in many-layered court dress], c. 1765-70. Ōban woodblock print. The British Museum (1906,1220,0.62)

Suzuki Harunobu (?–1770). [Poetess Ono no Komachi in many-layered court dress], c. 1765-70. Ōban woodblock print. The British Museum (1906,1220,0.62)

In addition to publishing popular readings, publishers controlled the entire production process of nishiki-e. Publishers found popular subjects, commissioned artists to draw block copies, and applied for publication permission from the authorities. Once permissions were granted, they sent the block copies to woodblock carvers and finally to woodblock printers for printing. The final products were displayed for sale at publishers’ stores (see image below). In addition to direct sales targeting pedestrian traffic in front of stores, publishers exchanged products with other publishers and sold to retail stores called ezōshiya.

Utagawa Toyokuni III (1786–1864) Merchant, from the Series Parodies of the Four Classes in the Modern Style, 1857. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Courtesy of the National Diet Library (寄別2-8-1-1)

Utagawa Toyokuni III (1786–1864) Merchant, from the Series Parodies of the Four Classes in the Modern Style, 1857. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Courtesy of the National Diet Library (寄別2-8-1-1)

The distribution network throughout Edo handled the sales of nishiki-e. Although few historical samples allow us to reconstruct the number of sheets printed for each set of nishiki-e, some records suggest the general production of one set yielded 1,000 to 1,500 sheets at the beginning of the 1840s. In the records of the late 1840s and later, 8,000 copies were printed for one set of blockbuster nishiki-e in about one month.

Nishiki-e were relatively inexpensive. The 1805 records show that one sheet of a standard size categorized as an ōban sheet, or large format (15 × 10 inches), was sold at twenty mon. No doubt, nishiki-e were within the reach of commoners. Shikitei Sanba’s novel Ukiyoburo (Ukiyo bath), published in 1809, depicts exchanges of nishiki-e among children at a public bath. Travelers from the countryside to Edo commonly bulk-purchased tens of nishiki-e as souvenirs.

By the end of the Edo period, one sheet of nishiki-e was typically sold at the retail price of about twenty-four mon, and some fetched only slightly more than thirty mon. Generally speaking, one sheet of nishiki-e is considered to have cost the equivalent of one bowl of soba noodle soup. A bowl of soba noodle soup cost sixteen mon, making the price of woodblock prints slightly higher. The price estimate here applies to standard woodblock prints. As described in Edo meisho zue—“Those that are gorgeously colored find fans of high status”—high-end products printed with highly refined techniques were sold at multiple times higher than those of standard quality.

I Nishiki-e as Mass Media

It is important to remember that nishiki-e were commercial products spearheaded by profit-minded publishers who hired teams of artists, carvers, and printers to collaborate on print series based on broad themes or one-off designs. Prints that include the word ōju (by special request) in the artist signature line indicate exclusive status, implying government endorsement—yet usually not being the product of it; nonetheless, these were the images conspicuously espousing policies of national strengthening, modernization, and patriotism.

A new censorship law, the Press Regulation (shinbunshi jōrei) enacted in 1875 required all nishiki-e designs to be submitted to the Home Ministry (Naimushō) for approval. Therefore, these prints, unlike stamps and currency, were not generated by the central government but were the products of free enterprise under the former’s watchful eye.

The dissemination of news by private channels, formerly inhibited by the Tokugawa regime, had a cautious start in the 1850s and quickly blossomed in the Meiji period. Nishiki-e did not seek to function like newspapers (shinbun) as a regular source of information and commentary. However, color prints published in the luxurious triptych format dramatized the excitement of the latest inventions, events, urbanscapes, conflicts, and celebrities. Coverage of Emperor Meiji fell in line with modern newspaper interest in explicating “civilization and enlightenment” (bunmei kaika) ideals to readers, a key difference being that nishiki-e also kept a foot in the old floating world (ukiyo) culture of sensual play and brassy entertainment.

Tōshū Shōgetsu (active ca. 1870–1904). The Third Domestic Industrial Exhibition at Ueno Park, December 1889. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.027)

Shinbun Nishiki-e

There was a hybrid form of news (shinbun) nishiki-e* that were single-sheet prints with text and image describing a current news story. These functioned differently from triptych nishiki-e, which did not necessarily deal with current events or include much text beyond the title. The rise in shinbun nishiki-e was in part an attempt to garner greater audience for an industry that was flagging just as the daily newspaper industry was burgeoning. Taking the most salacious stories from the daily newspapers and richly illustrating them in ōban prints was a short-lived boon to both industries.

| War Nishiki-e

Senso-e (war pictures) is a genre of Japanese art that specifically depicts military conflict, and its popularity in nishiki-e form peaked during the Meiji era. Combining the artistry of colorful woodblock prints with the often scrounged-together details of a far-off battle or victory, war nishiki-e were highly collected regardless of the accuracy of their depictions. Speed was of the essence as publishers fought to hit the market with the first depiction of an important event. This urgency uniquely allowed for the creation of works of art that at times gave talented artists leave to explore composition and color in dramatic and imaginative form, while at other times resulted in crude depictions far from the ukiyo-e standards of the day.

Early Depictions

The flourishing public appetite for visual updates from the front lines arose during the Boshin War (January 1868–June 1869), a civil war between the Tokugawa alliances and the new government army led by the Satsuma and Chōshū Domains, as censorship laws began to wane. Artists, however, were still hesitant to depict contemporaneous political events openly, leading to a rise of historical masking observed in nishiki-e of this time.

The civil war, which lasted over one year, kept the Edo people’s strong interest. Ukiyo-e artists used various ways to mimic civil war scenes, ranging from children’s snow fights to battles between animals and personified objects, to street-genre depictions in Edo, of which subjects in the woodblock prints implicitly speak of the war news. Many were still set in pre-Edo historical events.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–92). Scene of the Battle near Otai Castle in Shinano Province, 1868. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Courtesy of a private collection.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–92). Scene of the Battle near Otai Castle in Shinano Province, 1868. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Courtesy of a private collection.

One example is from Shinshū Otaijō kassen no zu (Scene of the battle near Otai Castle in Shinano Province), illustrated by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (see above). The nishiki-e supposedly depicts the 1544 attack on Lord Odai Matarokurō’s castle, which was destroyed by the neighboring lord Takeda Shingen. But the woodblock print is full of more contemporary depictions, underscoring its true intention of reporting the Battle of Iiyama in Shinano Province, a conflict between the new government and a deserter unit from the Tokugawa shogunate army on April 25, 1868, a quick production turnaround after receiving a publication approval from the authorities in May 1868. For example, both armies are fully armed with guns, an improbable outfit only one year after the Portuguese introduced the first guns to Japan. The soldiers on the right are wearing military uniforms similar to the Western style from the end of the Edo period, not in 1544.

As Scene of the Battle near Otai Castle in Shinano Province demonstrates, the Boshin War nishiki-e set a precedent for quick production and sale in Edo after a fight occurred. Most of the artists never set foot on the battle sites, except for the Kan’eiji temple in the Battle of Ueno in Edo. However, their imagined illustrations provided sufficient war journalism to the masses. The volume production of Boshin War woodblock prints perhaps gave rise to the war pictures during the Meiji era.

Meiji War Nishiki-e

The Satsuma Rebellion, 1877

During the massive changes of this epoch, the Satsuma Rebellion first caught many nishiki-e artists’ eyes. As in the Boshin War, no nishiki-e artists traveled to the battle sites in southern Kyushu (the southernmost island of Japan’s main islands), far away from Tokyo. They drew battle scenes based on newspaper reports. Since photography was still underdeveloped, the popular masses welcomed the visual representation of fierce fights in Meiji woodblock prints and their continued war media function. Many nishiki-e carried retail prices on the prints. A set of three large-format prints was sold for six sen, its price-adjusted value apparently not much different from what it was at the end of the Edo period.

Yamazaki Tokusaburō (1857–86). Overview of the Great Japanese Navy and Army, April 21, 1878. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.001)

The Imo Incident, 1882

An unexpected overseas event, the Imo Incident caused the small Japanese legation in Seoul, Korea, to flee the rioting city as their legation building burned. With apparently no journalists on the scene, and a public hungry for news of the event, nishiki-e artists sated appetites by relying on information provided directly from the government to the media. The initial source the government shared was a telegram report sent to the Japanese minister of foreign affairs, Inoue Kaoru, from Hanabusa Yoshitada, the minister to Korea, who was on the scene and ordered the burning of the legation building. It stated that:

On July 23 Meiji 15 [1882] at five in the afternoon, hundreds of violent rioters suddenly attacked our legation with arrows, rocks, and guns. […] the members of the legation ran from the fire […] rode on a small boat to get to Chemulpo and rode the English vessel Flying Fish […] arrived at Nagasaki on [July] 29.

This text explains the incident and was repeated verbatim in the Yomiuri shimbun dated August 1, 1882. Articles in the following weeks repeated the message and those of other legation members, as well as information from later ministerial meetings. Not only did nishiki-e artists rely on this report, they also incorporated the text into their prints.

Yōshū (Hashimoto) Chikanobu (1838–1912). Record of the Korean Incident, August 10, 1882. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.043)

Yōshū (Hashimoto) Chikanobu (1838–1912). Record of the Korean Incident, August 10, 1882. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.043)

Chōsen bōto bōgyo-zu (Defense Against Korean Mobs) and Chōsun jikenki (Record of the Korean Incident) demonstrate this, and the text also informs their imagery. However, even if there had been some shooting and crossing of swords, there would not have been the magnificent battle scenarios depicted. Due to their small number, the Japanese legation and their guards would more likely have tried to make a stealthy escape as aggressive crowds focused on the legation building. Other components of the prints maintain some authenticity of place—the colorful attire of the rioting Korean soldiers, the throne hall of the royal palace, the legation’s flight through the Namdaemun (southern city gate) to an escape by water. Overall, the factual combined with artistic license composes a dramatic scene that casts the Japanese in a heroic position—something that inescapably promotes nationalism propagandistically rather than objectively recount the event.

Utagawa Kunimatsu (1855–1944). The Defense Against Korean Mobs, August 20, 1882. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.044)

The First Sino-Japanese War, 1894–95

The second peak of war prints during the Meiji era occurred when Japan fought with Qing China over political and military influence in the Korean peninsula. The war acted as a catalyst for the declining ukiyo-e world, which suffered from the death of popular artists like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and Toyohara Kunichika and the rise of multicolored prints using Western lithography. Up to three thousand Sino-Japanese War prints are considered to have been produced.

Fighting began with the naval battle of Pungdo on July 25, 1894, followed by the first land battle in Seonghwan and Asan. It was not until August 1, one week later, when Japan and Qing China declared war. On the same day, the Japanese government issued an emergency decree (decree 134), requiring newspaper and magazine publishers, and the creators of play scripts, to receive permission from the Home Ministry in Tokyo or their local governments if they sought to publish diplomatic or military-related articles. Rival nishiki-e makers, known for their equally speedy reportage, petitioned the Home Ministry to shorten the decision process from about one week to the same day.

Despite a slight delay due to the new censorship rules, by August 9, Tsujioka Bunsuke’s woodblock store and printer located in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, inaugurated the first Sino-Japanese War–related sensō (war) nishiki-e. Yōshū (Toyohara) Chikanobu (1838–1912), who had already gained a reputation for his nishiki-e on the Satsuma Rebellion (1877), created the ōban triptych woodblock prints titled Ōtori kōshi Kantei sandai (Minister Otori visits the Korean court), Toyoshima(oki) kaisen (The naval battle of Pungdo), and Seikan gekisen (A fierce battle in Seonghwan). About the same time, by July 25, the Ogawa Photographic Plate Maker produced pictures of the Chinese gunboat Caojiang captured in the Battle of Pungdo. Matsuzawadō, located in Tameike, Akasaka, Tokyo, then sold them. Pictures produced using the new printing techniques of collotype printing and halftone were adequate for documenting still images of battleships and armies. However, they could not compete with painters and writers, who were masters of dynamic battle scene depictions—what the Japanese masses demanded for arousing fever and excitement.

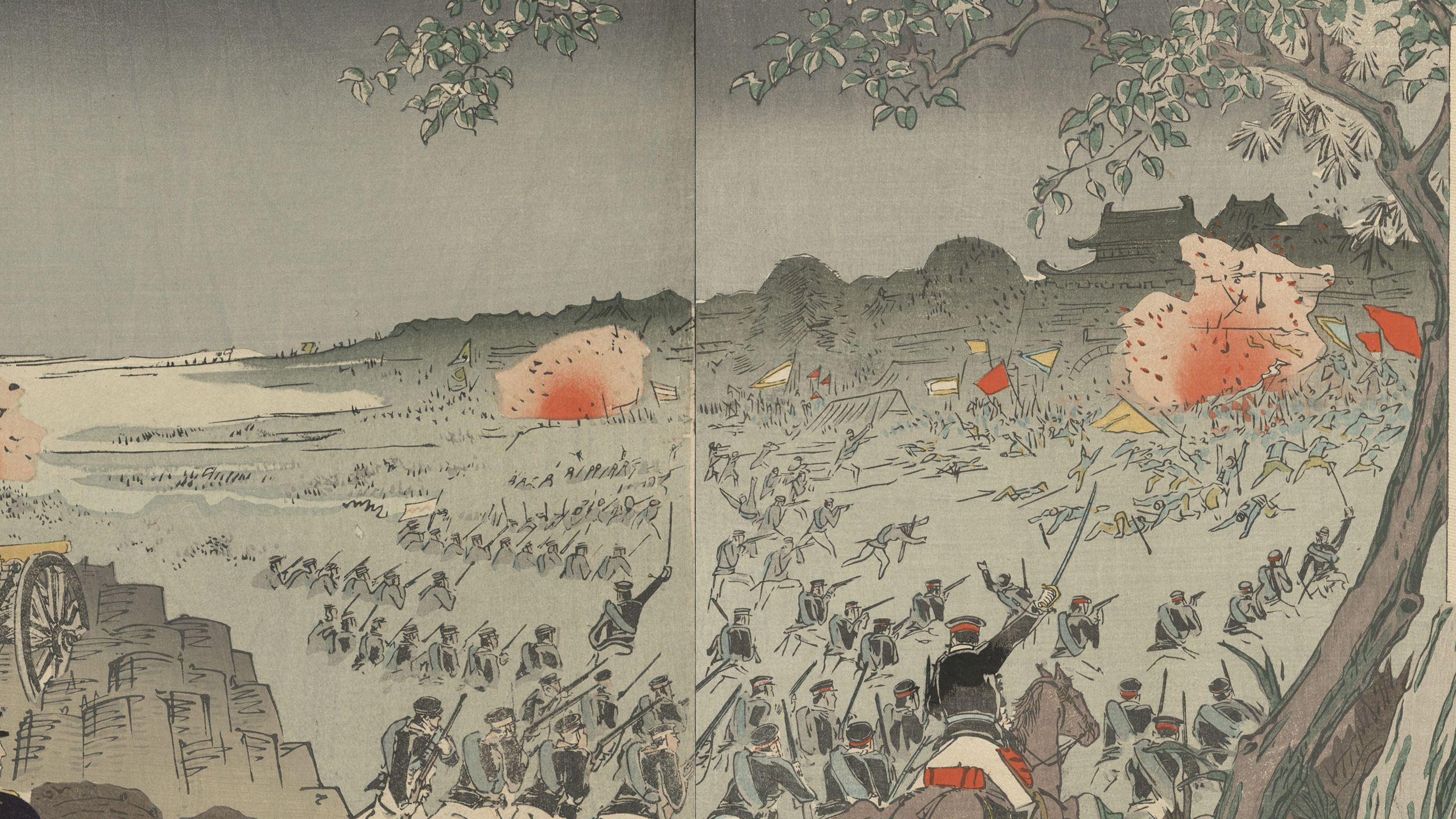

Migita Toshihide (1863–1925). Invincible: The Fall of Pyongyang, 1894. Central triptych of an ōban enneaptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Migita Toshihide (1863–1925). Invincible: The Fall of Pyongyang, 1894. Central triptych of an ōban enneaptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Migita Toshihide (1863–1925). Surprise Attack: The Capture of Pyongyang, 1894. Right-most triptych of an ōban enneaptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Migita Toshihide (1863–1925). Surprise Attack: The Capture of Pyongyang, 1894. Right-most triptych of an ōban enneaptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Migita Toshihide (1863–1925). The Beautiful Tale of the Heroic Soldier Shirakami, 1895. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.016)

Migita Toshihide (1863–1925). The Beautiful Tale of the Heroic Soldier Shirakami, 1895. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.016)

Utagawa Kuniteru III (1848–1920) / signed Toyosu. General Nozu’s Great Victory after the Fierce Battle at Pyongyang, September 1894. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.007)

Utagawa Kuniteru III (1848–1920) / signed Toyosu. General Nozu’s Great Victory after the Fierce Battle at Pyongyang, September 1894. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.007)

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915). In Clear Weather after Snow, General Nozu’s Advance on Liaoyang, 1895. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.015)

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915). In Clear Weather after Snow, General Nozu’s Advance on Liaoyang, 1895. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives (2019C113.015)

The Russo-Japanese War, 1904–05

The last episode of war print nishiki-e took place during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), when Japan and the Russian Empire fought over their interests in the Korean peninsula and southern Manchuria. Despite substantial popular interest in the war, nishiki-e production was far less than in the Sino-Japanese War.

The role of nishiki-e as a source of news had diminished. Replacing woodblock prints were photographs produced by better-established photo-printing techniques, like those in albums of battle scenes and magazines with rich photographic plates like Nichi-Ro sensō shashin gahō (Pictorial magazine of the Russo-Japanese War). Popular demand called for more realistic depictions of the war created by eyewitness artists on the battlefield, instead of imaginary warrior prints.

Postcards also changed the market dynamics of nishiki-e after the Meiji government allowed their private production in 1900. Postcards of Russo-Japanese War photographs became a megahit, replacing nishiki-e on the top shelves of ezōshi stores. This shift in popularity was the final blow to nishiki-e, and its over-two-century history entered its concluding chapter. Nonetheless, artists like Kobayashi Kiyochika, Baidō Kokunimasa, and Migita Toshihide undoubtedly created more dramatic and powerful battle scenes than any black-and-white pictures could.

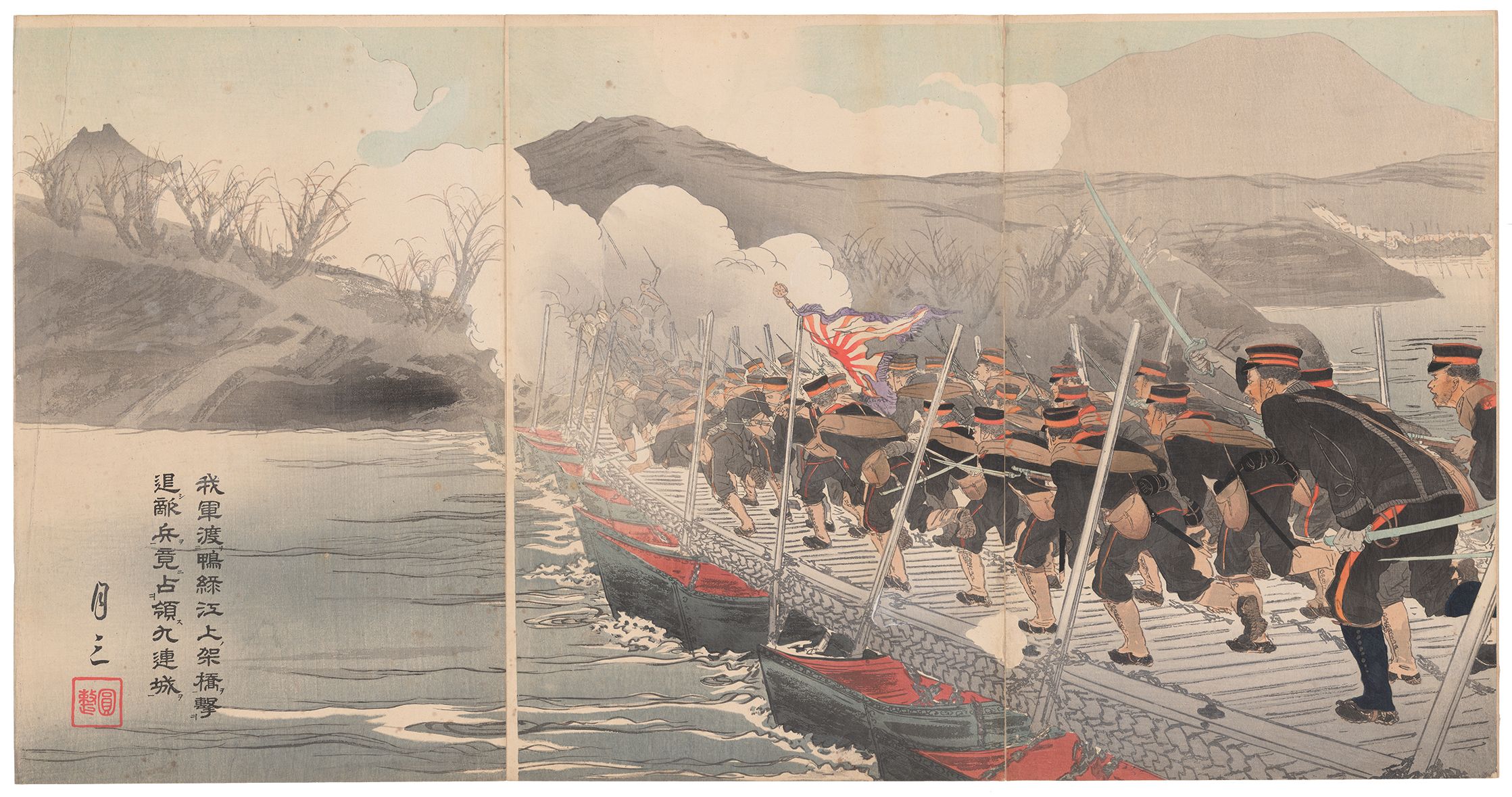

Ogata Gessan (1887–1967). Our Army Crosses the Yalu River on the Pontoon Bridge and Drives Back the Enemy Forces to Finally Occupy Jiuliancheng, 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Ogata Gessan (1887–1967). Our Army Crosses the Yalu River on the Pontoon Bridge and Drives Back the Enemy Forces to Finally Occupy Jiuliancheng, 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

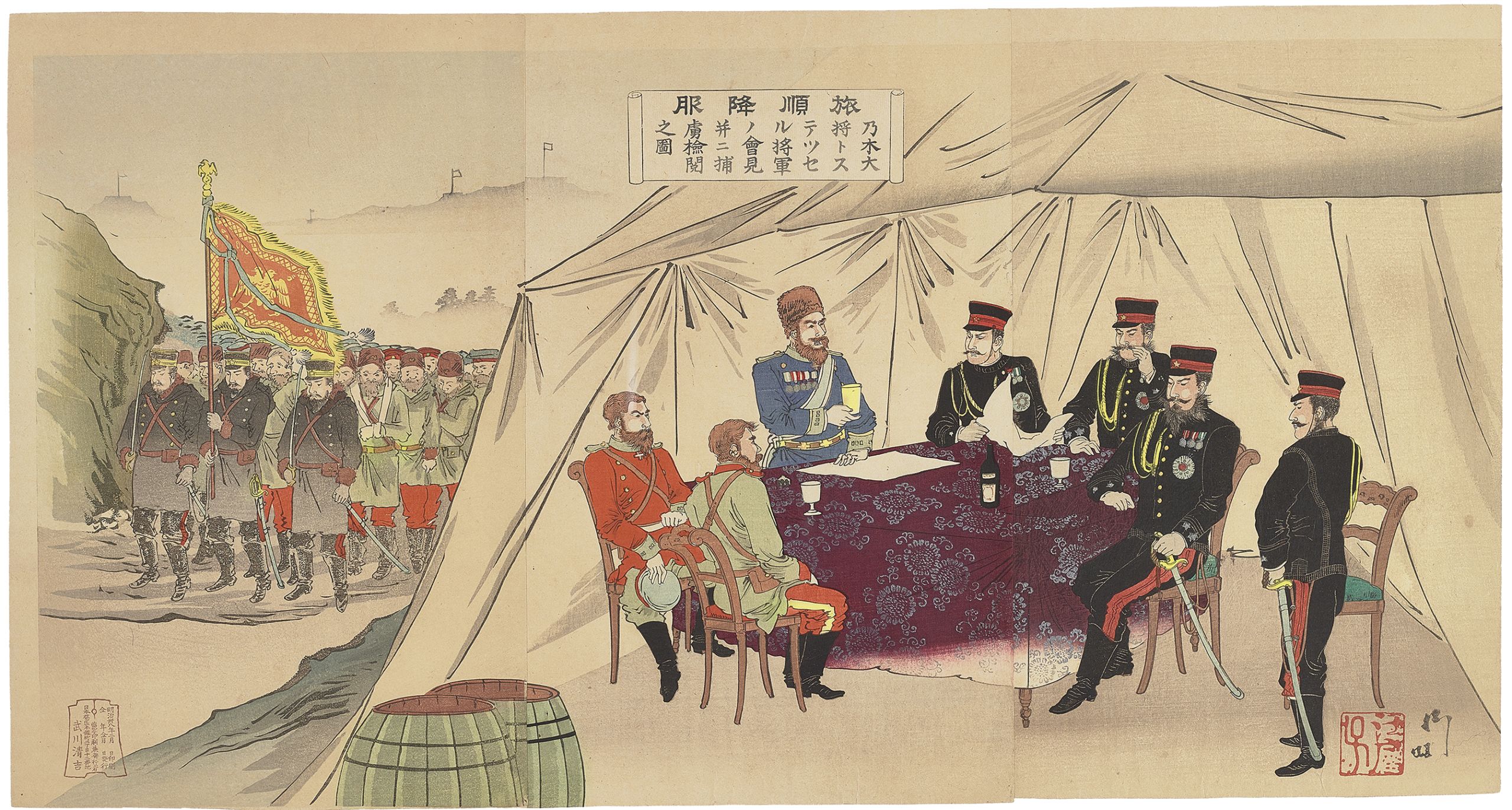

Utagawa Kokunimasa (1874–1944). The Surrender of Port Arthur: General Nogi and General Stessel's Meeting and Inspection of Prisoners of War, 1905. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Utagawa Kokunimasa (1874–1944). The Surrender of Port Arthur: General Nogi and General Stessel's Meeting and Inspection of Prisoners of War, 1905. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

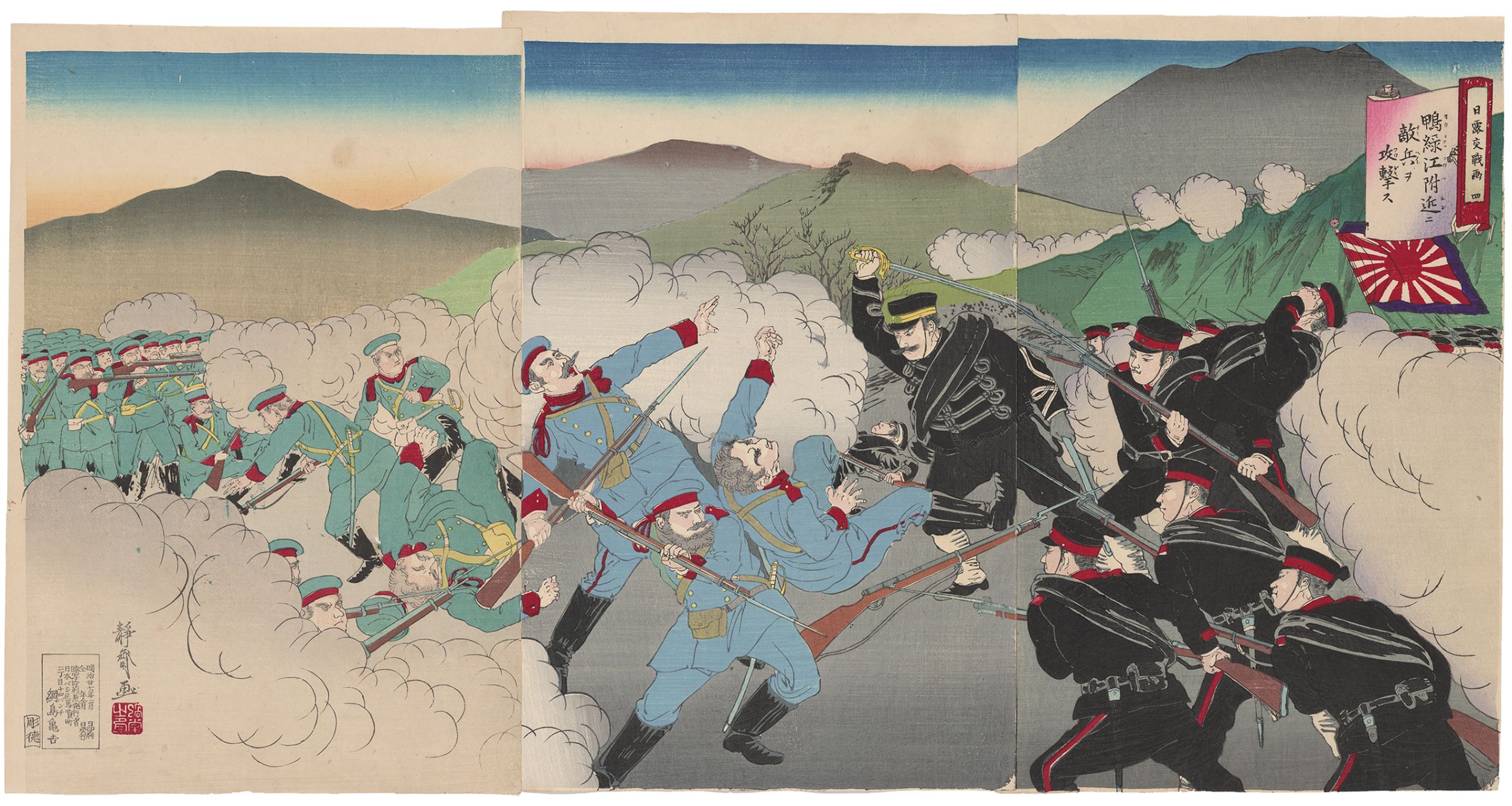

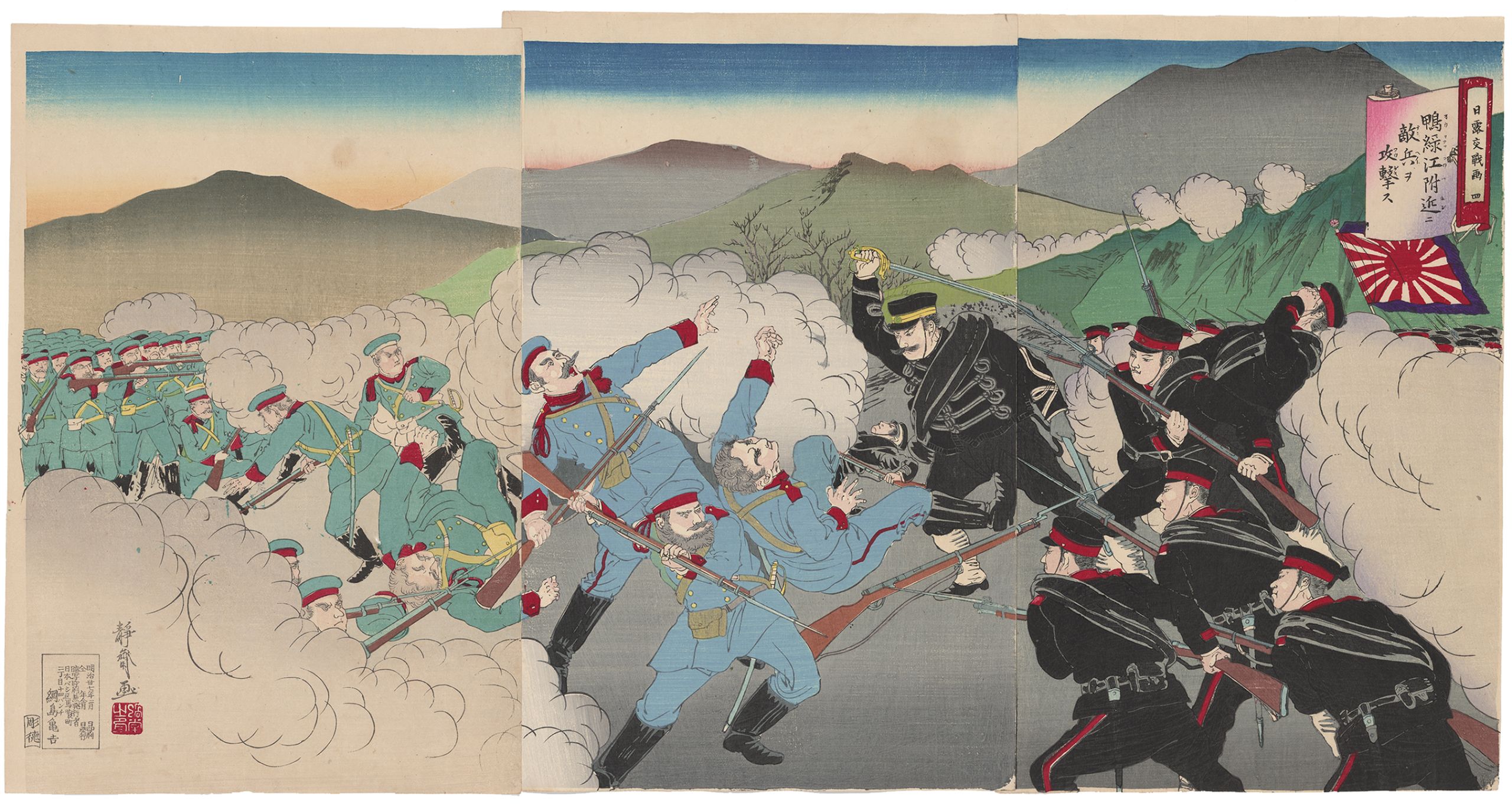

Itō Seisai (active 1904). Russo-Japanese War Battle Scene 4: Attacking the Enemy near the Yalu River, February 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Itō Seisai (active 1904). Russo-Japanese War Battle Scene 4: Attacking the Enemy near the Yalu River, February 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

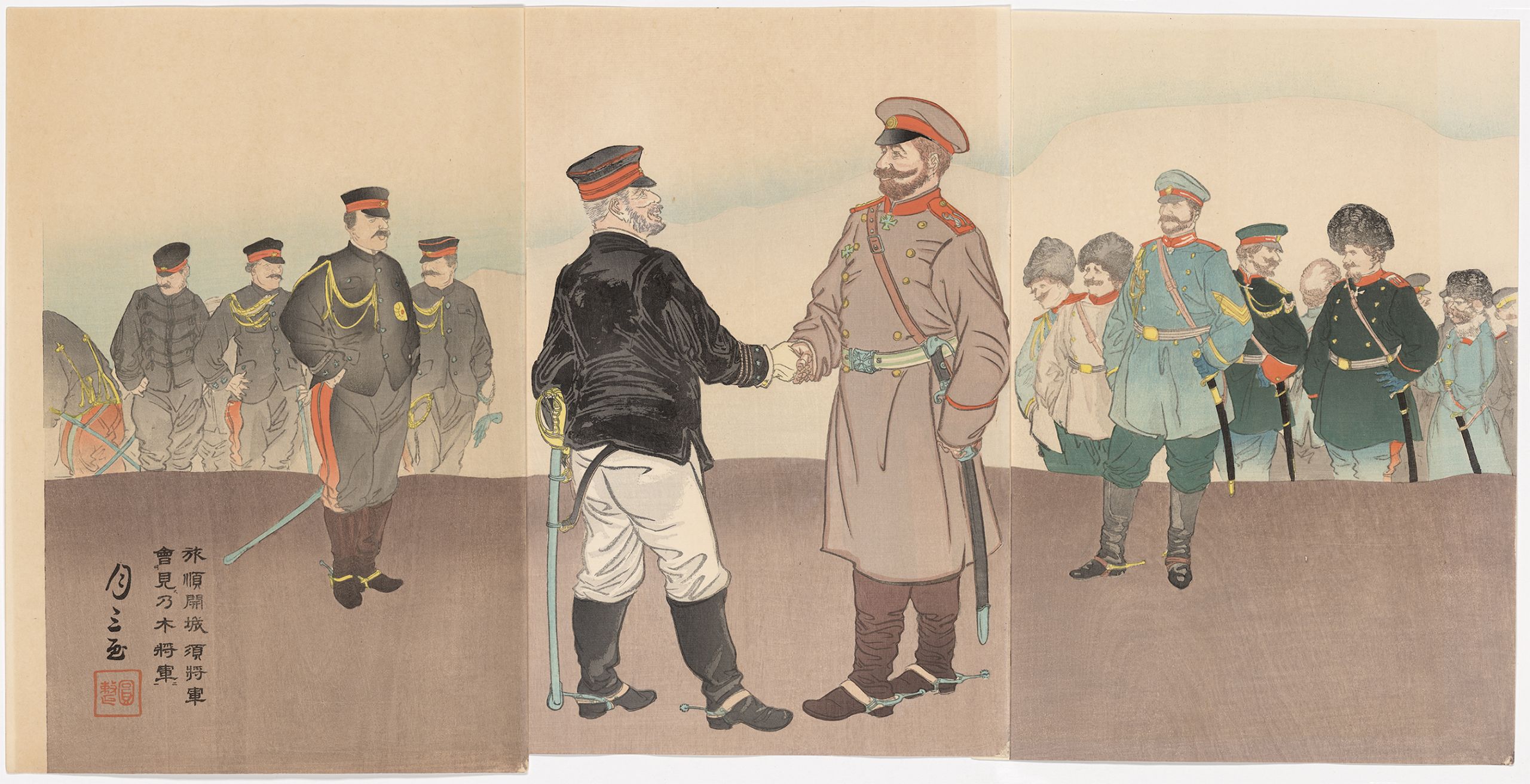

月三 Gessan. The surrender of Port Arthur, General Stessel meets with General Nogi, 1905. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

月三 Gessan. The surrender of Port Arthur, General Stessel meets with General Nogi, 1905. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

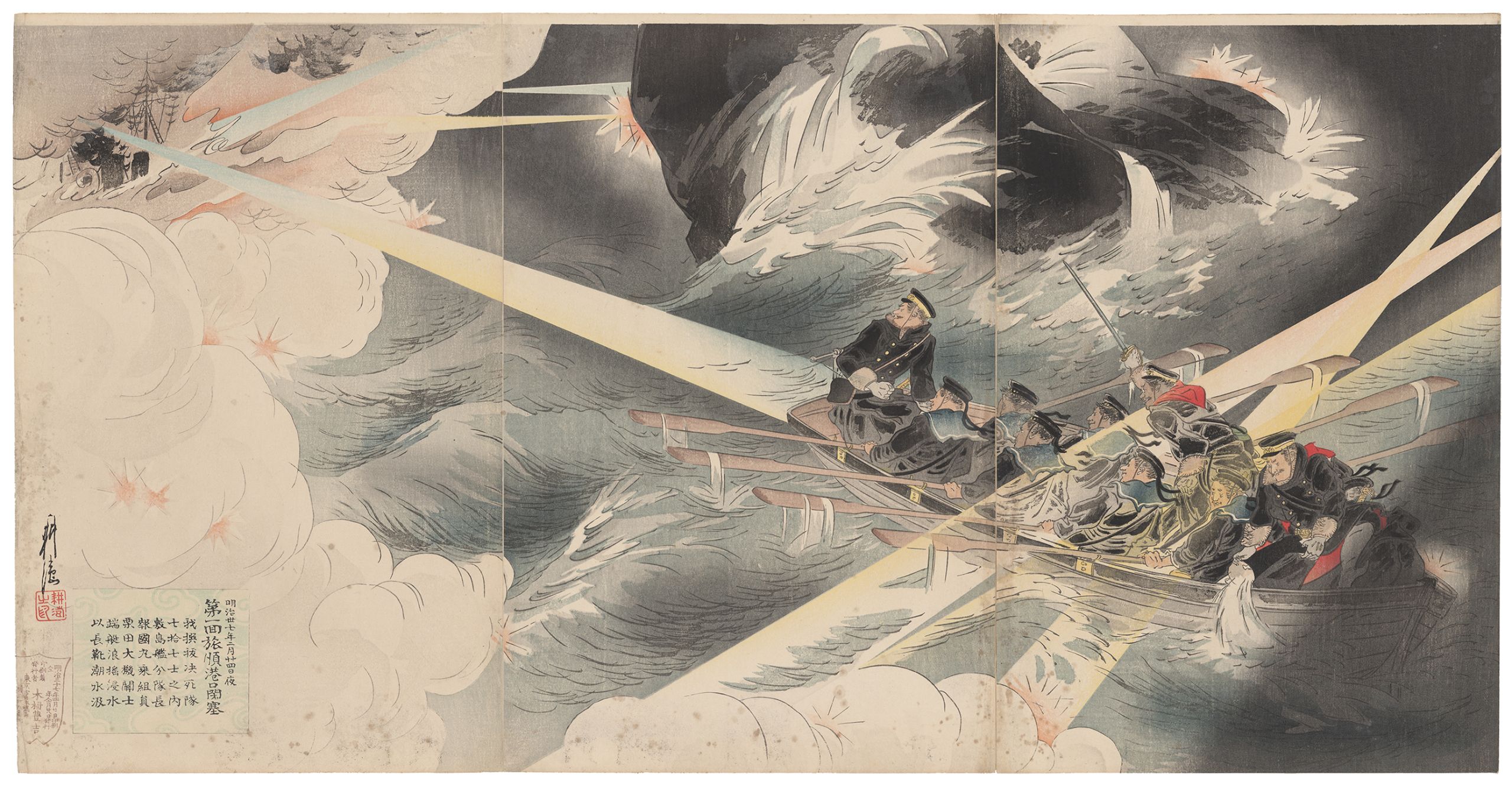

Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927). The First Blockade of Port Arthur, the Night of February 24, 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Tsukioka Kōgyo (1869–1927). The First Blockade of Port Arthur, the Night of February 24, 1904. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Postscript

The Shanghai Incident (January 28–March 3, 1932) is an episode in East Asian history overshadowed by bloodier conflicts of the twentieth century. It gave Japan the war heroes posthumously deified as Bakudan san’yūshi (literally “exploding bomb three heroes”). These men, according to modern Japanese lore, sacrificed themselves for the greater good of the nation by making a suicide charge against an enemy stronghold near Miaohang village, north of Shanghai’s International Settlement, on February 22, 1932.

Evidence of the Bakudan san’yūshi craze can be found in nearly all spheres of Japanese life between 1932 and 1945. Put simply, it was an unparalleled media and cultural sensation. It even had a strong enough resonance to revive interest in war nishiki-e, as the artist Hasegawa Sadanobu III (1881–1963) quickly produced a dynamic example capturing the chaos of the battle and steely intention of the bombers.

Hasegawa Sadanobu III (1881–1963) / signed Konobu III. Three Brave Bombers, April 1932. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

Hasegawa Sadanobu III (1881–1963) / signed Konobu III. Three Brave Bombers, April 1932. Ōban triptych woodblock print. Japanese Woodblock Print Collection, Hoover Institution Archives

This introductory material includes passages originally published in Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan (2021) by contributors Michael R. Auslin, Toshihiko Kishi, Hanae Kurihara Kramer, Scott Kramer, Barak Kushner, Olivia Morello, Junichi Okubo, Alice Y. Tseng, and Kaoru (Kay) Ueda. We are most thankful for their permission to use the materials online.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team. For more information about rights and permissions please visit:https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.

![Suzuki Harunobu (?–1770). [Poetess Ono no Komachi in many-layered court dress], c. 1765-70. Ōban woodblock print. The British Museum](https://fanningtheflames.hoover.org/sites/default/files/shorthand/stories/Xtd5hDR13y/979b283e-1636-4970-a98e-1668144d942d/assets/7kj0pEIhZt/harunobu-421043001-1062x1440.jpeg)