The Rise of Empire

A Core Topic of Modern Japan

Around 1800, Western whaling and merchant ships and gunboats began frequenting Japanese waters along with the already-permitted Dutch and Chinese merchant ships. The Tokugawa shogunate government (1603–1868) could no longer isolate its territories from the rest of the world. One of several significant and threatening events was Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s arrival in Japan from Norfolk, Virginia, in 1853. Arguably, the domestic political, economic, and social currents in Japan were already ripe for sweeping changes. The impending Meiji Restoration would usher the nation into the modern era as the Empire of Japan.

Black Ships and Commodore Perry

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, American ships out of New England had sailed the waters around Japan for fishing, whaling, and trade, yet they were prohibited from going ashore. Regardless of their need for supplies or even emergency care, Japan’s sakoku (closed country) policy kept relations and trade severely limited, and even the unfortunate survivors of shipwrecks found themselves harshly treated when washed ashore.

When the sakoku policy came into effect in 1639, foreigners were expelled, travel abroad by Japanese was prohibited, and Christianity was forbidden, with practitioners severely punished. Yet a small foothold was retained by the Dutch on an island in Nagasaki harbor. In the subsequent two centuries, Japan had a flourishing insular economy that was self-sufficient and a stable national security that allowed warriors to become bureaucrats focused on enhancing the infrastructure of the nation.

By 1852, however, the nascent United States became incredulous at its exclusion from Japan. US President Millard Fillmore assigned Matthew C. Perry the task of breaking Japanese isolationism—through gunboat diplomacy if needed. Steaming into Edo Bay on July 8, 1853, Perry brought Japan’s leaders a message demanding that castaways be given humane treatment; that whalers and other American vessels be provided ports of call with access to coal, provisions, and water; and that mutually beneficial trade relations be established.

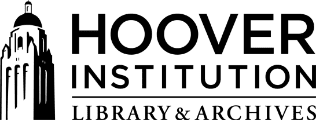

Perry’s warships were not a surprise in the waters off Uraga; however, his use of firepower as intimidation proved successful where previous attempts had fallen short. On July 14, his party of roughly 300 Americans was the first allowed ashore in Edo Bay, in an area just outside what was to become the open port of Yokohama. Three days later Perry and his four vessels left with a promise to return.

Eight months later Perry kept that promise, returning with nine vessels that carried over 100 mounted guns and a crew close to 1,800. There was much more interaction between the Americans and the Japanese on this visit, and on March 31, 1854, a treaty was signed in Kanagawa in which the Japanese met all of the American requests. The visit laid the groundwork for the further opening of Japan to the rest of the world, and for the changes wrought by the fast-approaching Meiji Restoration.

Commodore Perry's Second Fleet. View of the Vessels Composing the Japanese Squadron, 1854. Colored engraving. Wikimedia Commons

Commodore Perry's Second Fleet. View of the Vessels Composing the Japanese Squadron, 1854. Colored engraving. Wikimedia Commons

Depictions of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, circa 1854. Top woodblock print: Library of Congress. Bottom woodblock print: Ryosenji Treasure Museum. Right daguerreotype: Wikimedia Commons.

Depictions of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, circa 1854. Top woodblock print: Library of Congress. Bottom woodblock print: Ryosenji Treasure Museum. Right daguerreotype: Wikimedia Commons.

Top: The Americans Landing at Yokohama in 27 Barges. Japanese handscroll. ©The British Museum (2013,3002.1). Bottom: Landing of Commodore Perry, Officers and Men of the Squadron to Meet the Imperial Commissioners at Yokohama, Japan, March 8th, 1854. Detail of lithograph after painting by William Heine (1825–85). Yokohama Archives of History.

Top: The Americans Landing at Yokohama in 27 Barges. Japanese handscroll. ©The British Museum (2013,3002.1). Bottom: Landing of Commodore Perry, Officers and Men of the Squadron to Meet the Imperial Commissioners at Yokohama, Japan, March 8th, 1854. Detail of lithograph after painting by William Heine (1825–85). Yokohama Archives of History.

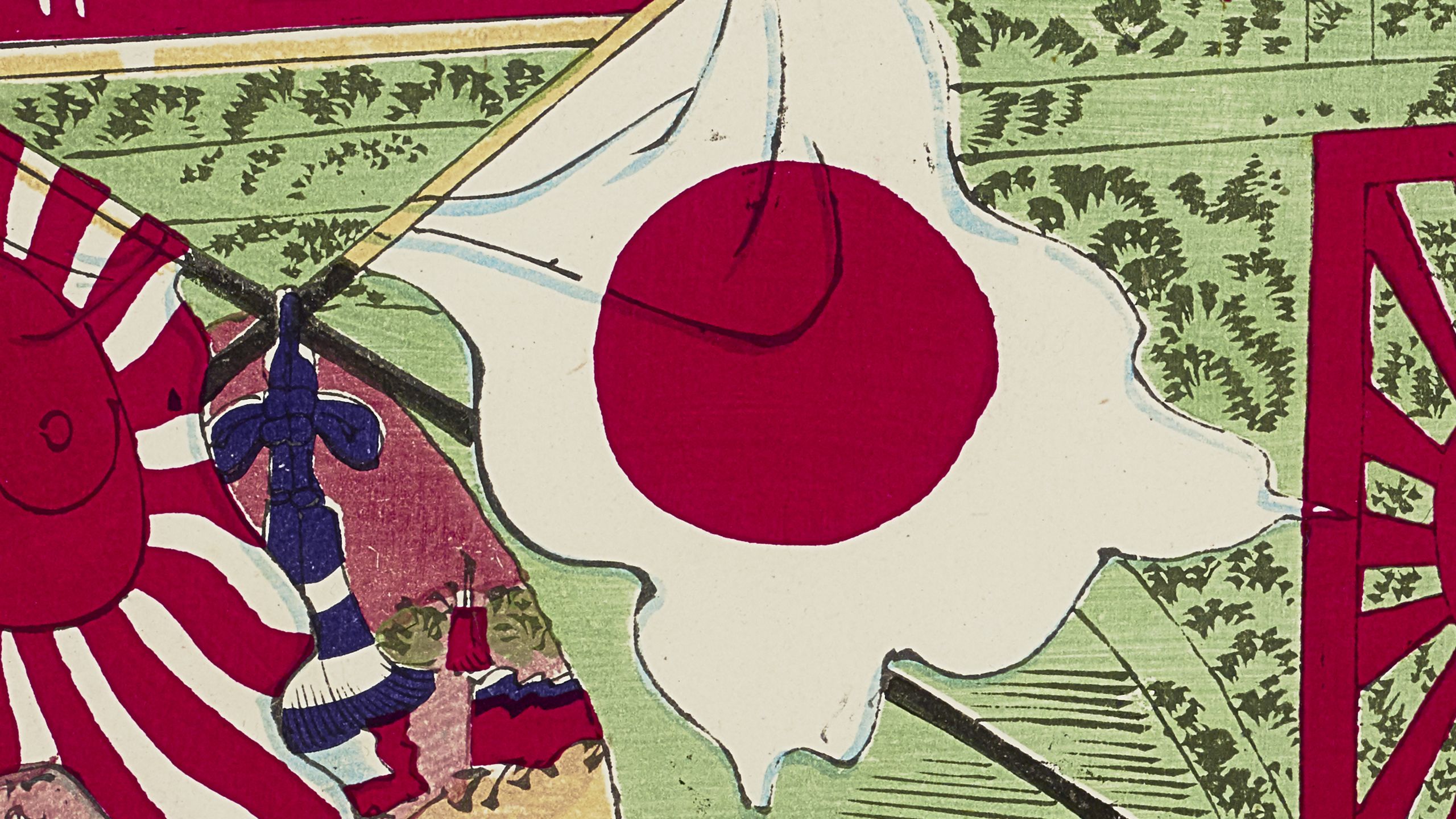

The Meiji Restoration

![His Majesty the Commander in Chief's Triumphal Return to the Palace [Diet Building], June 1895. Unsigned ōban triptych woodblock print. Hoover Institution Archives (2019c113.018)](https://fanningtheflames.hoover.org/sites/default/files/shorthand/stories/KXF2p07eRz/d01b2cb2-8e4a-44b6-b330-1d33bae01196/assets/InHgCje56V/2019c113_018-trim-2560x1440.jpeg)

On the first day of January 1868, an improbable combination of midranking samurai from Japan’s outer feudal domains and imperial courtiers at the center of society overthrew the 265-year-old Tokugawa bakufu (shogunate) and promulgated what became known as the Meiji Restoration. From the moment they took power, they grappled with the challenge of making a modern nation that could survive in a world dominated by Western imperialist states. The task of forging a new nation, one centered on the young Emperor Mutsuhito, would demand a comprehensive reimagining of the fundamental features of Japanese civilization.

After seven centuries of feudal rule, the usurpers-cum-oligarchs had to decide just how far they would pursue the process of political centralization, what the future would be of the over two hundred feudal domains that made up the political framework of the country, and whether they should maintain or scrap the social caste system imposed by the Tokugawa that privileged the numerically inferior samurai over all other segments of society. Aside these first-order questions were equally crucial issues of creating a modern military that could defend Japan against the imperial Western nations and building an economy that was both modern and national.

To escape from the danger of Western encroachment— the fate that the Qing dynasty, once the “sleeping lion” in Asia, suffered after the Opium Wars—Japan hurriedly instituted political, economic, and social reforms to turn itself into a unified modern nation-state. The position of the emperor played a pivotal role in creating the new Japan. However, standing in the way of asserting independence were unequal treaties with Western nations. How to improve their international status and convince Western powers that Japan was worthy of equal bilateral treatment was a key question Japan answered with westernization and modernization through a movement known as bunmei kaika (civilization and enlightenment). The Meiji government also strove to strengthen the imperial military, and to reform economic activities to finance it, under the slogan fukoku kyōhei (Enrich the country, strengthen the armed forces).⁴ Arguably, establishing a new order in Asia under Japanese hegemony—as epitomized by Fukuzawa Yukichi’s famed call for “de-Asianization,” or for Japan to “leave Asia”—was one way of distancing Japan from the “uncivilized” realm and elevating its status to join the “civilized.”⁵

Japan in the latter third of the nineteenth century was one of the more literate countries on earth, an advantage that would become evident as the Meiji government began creating a modern nation-state. Samurai, who had long given up active use of the sword in favor of the pen, had served for centuries as administrators, bureaucrats, and clerks, all using the written word to produce untold thousands of official documents. Merchants, who during the long Tokugawa peace had begun creating a national economy linked by coastal shipping and credit mechanisms, were similarly dependent on written accounting methods. Urban booksellers did a brisk trade, as did early lending libraries, providing often lavishly illustrated volumes of vernacular fiction, domestic travel guidebooks, and descriptions of urban life in Edo and other major cities. Meanwhile, news sellers catered to patrons eagerly awaiting penny broadsheets that combined often-sensationalized imagery—such as depictions of Commodore Perry’s fire-breathing steam vessels that arrived in 1853—with pithy news accounts. Even rural peasants gathered in reading groups, their children taught in local Buddhist temple schools.

Ironically, Japanese could not carry out its modernization without help from North Americans and Europeans. Western ideas, systems, customs, and technologies made significant inroads into Japanese life: railroads, telegrams, the postal service, education systems, military service, large-scale agriculture, gas lighting, hairstyles, and even Western trousers and dresses, to name a few. Many were American contributions.

The relatively bloodless Meiji Restoration, and subsequent Boshin Civil War in 1868–69, propelled Japan’s expansionist interests. Even though it had been an emerging nation at the brink of Western encroachment, Japan’s interest in appropriating Western-style imperialism to its agenda was evident from the early Meiji era. Somewhat ironically, Japanese use of gunboat diplomacy in the vein of Commodore Perry led to its treaty with Korea in 1876 and the opening of that country to Japan without Qing Chinese intermediaries. As its influence spread on the Korean peninsula, Japan strategically used events such as the Imo Incident of 1882 to enhance its strength in the region.

Then, barely forty years after the arrival of Perry in the archipelago, Japan launched its first overseas military campaign against Qing China over interests on the Korean peninsula. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) marks a turning point for Japan from cautiously navigating through the currents of Western colonialism in Asia to being an imperialist itself. Japan was looking for a pretext to expand its national interests on the Korean peninsula, but Qing China, which had already enjoyed a military presence there, stood in its way. Released from its long-term isolationist policy, Japan transformed the humiliation inflicted by Western nations into overseas expansion and experimented with its own version of imperialism in Asia.

Edoardo Chiossone (1833–98), Maruki Riyō (1854–1923), H.I.M. The Emperor of Japan, insert facing page 32 in The War in the Far East, 1904–1905, 1905. Photogravure of a conté drawing. Hoover Institution Library (DS517.13 .R425)

Edoardo Chiossone (1833–98), Maruki Riyō (1854–1923), H.I.M. The Emperor of Japan, insert facing page 32 in The War in the Far East, 1904–1905, 1905. Photogravure of a conté drawing. Hoover Institution Library (DS517.13 .R425)

Expanding Empire

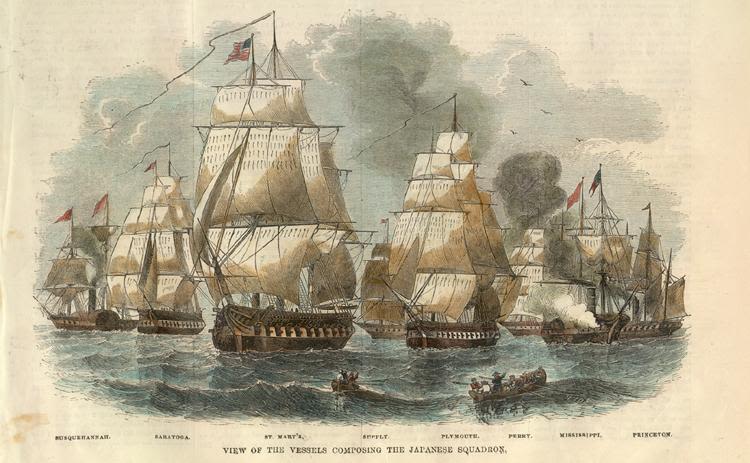

Victory in the First Sino-Japanese War left Japan ready to expand its influence. It was now positioned as the dominant Asian nation, having extinguished Qing control over Korea, and the peace treaty of Shimonoseki granted it the territorial gains of Taiwan (then known as Formosa) and select groups of neighboring islands. The West watched closely to ensure its interests in the region were not impinged upon, and ultimately Russia and its allies stepped in to nullify part of the treaty to keep the strategic Lioadong Peninsula out of Japanese control.

With the Qing dynasty crumbling, European powers began to flex their strength in China, and Japan was eager to do the same. As Russia, Germany, France, and Britain opened ports and pushed their colonial interests, Japan attempted similar moves, though less successfully. In particular, Japan’s newly won influence over Korea was quickly snatched up by Russia, as was control over the Liaodong Peninsula. However, events like the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), in which Britain called upon the Japanese military for assistance in quelling Chinese rebels, continued to enhance Japan’s international standing.

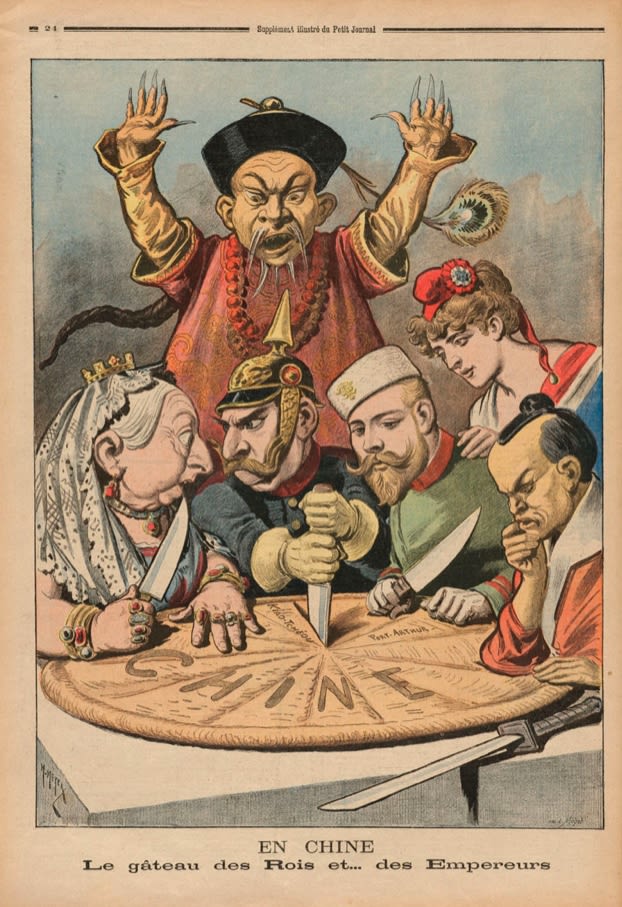

After ten years learning about and taking the measure of the European nations in its midst, Japan set to work attaining what it had desired from Qing China—the Liaodong Peninsula and influential control over Korea. The Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) was a calculated risk by Japan, which was tired of the endless encroachment of Russia into East Asia. Japan achieved a decisive victory, surprising much of the Western world. However, the lack of official territorial gains or financial reparations meant the people of Japan were left disillusioned—especially with the increasing regional influence of the treaty arbiter, the United States.

The Russo-Japanese War gave Japan protectorate status over Korea, which it annexed in 1910, and influence over Inner Manchuria. When the First World War broke out in 1914, Japan joined the Allies and used the conflict to its advantage, seizing control of the vast German interests in China’s Shandong Province and western Pacific islands, such as the Marshalls and German New Guinea. The eventual outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917 was also leveraged effectively with extended, albeit short-lived, influence over Outer Manchuria.

As nationalistic militarism swept through Japan, propagandistic messaging of itself as a champion of liberty for the Western-colonized people of East Asia entwined with notions of brotherhood with the peoples under its own rule in an attempt to obscure perceptions of its colonial activities. The 1931 Manchurian Incident provided a key opportunity for the “liberation” of the Manchu people from Han Chinese rule and evolved into Japan’s recognition and puppeteering of the state of Manchukuo.

This period saw Japan develop the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere campaign, to further justify an expansion of its empire. With varying goals and directives, Japan’s aggression in China began the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45). World War II then saw the furthest extent of Japanese imperial rule ever reached, but by 1945 the Empire of Japan expired. Its defeat by the Allies stripped it of lands outside the traditional pre-1895 Japanese cultural sphere, changed the nation into a parliamentary democracy with the emperor as a mere figurehead, and left the nation devoid of expansionist capacity. Instead Japan’s focus shifted to rebuilding the nation economically with an international agenda centered on peace.

Henri Meyer, “En Chine: Le gâteau des Rois et... des Empereurs.” Le Petit Journal Supplément Illustré, January 16, 1898. Cornell University Library (1129.01)

Henri Meyer, “En Chine: Le gâteau des Rois et... des Empereurs.” Le Petit Journal Supplément Illustré, January 16, 1898. Cornell University Library (1129.01)

The Illustration of the Great European War. A Humorous Atlas of the World, circa 1914-18. Tokyo: Shobido & Co. Poster Collection, JA 37, Hoover Institution Archives.

The Illustration of the Great European War. A Humorous Atlas of the World, circa 1914-18. Tokyo: Shobido & Co. Poster Collection, JA 37, Hoover Institution Archives.

Japan, China and Manchu Help One Another, the World Is in Peace, circa 1937. Poster Collection, JA 55, Hoover Institution Archives.

Japan, China and Manchu Help One Another, the World Is in Peace, circa 1937. Poster Collection, JA 55, Hoover Institution Archives.

Map Showing the Furthest Extent of the Empire of Japan during World War II. Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Map Showing the Furthest Extent of the Empire of Japan during World War II. Hoover Institution Library & Archives

This introductory material includes passages originally published in Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan (2021) by contributors Michael Auslin, Barak Kushner, Olivia Morello, and Kaoru “Kay” Ueda. We are most thankful for their permission to use the materials online.

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. If you would like to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this resource or have concerns about the inclusion of an item, please contact the Hoover exhibits team. For more information about rights and permissions please visit:https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/get-help/rights-and-permissions.